Carbohydrate Counting in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes (CCAT

advertisement

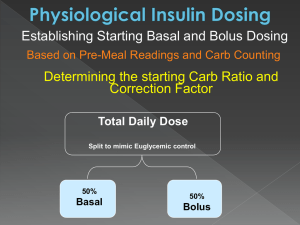

Carbohydrate Counting in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes Management of Diabetes in Youth, Biennial Conference of the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes July 12-16th, Keystone, Colorado David Maahs, Darcy Owen, Franziska Bishop Outline Overview of data/literature on and rationale for carbohydrate counting in diabetes Overview of practical aspects of carbohydrate counting (i.e. what happens when the MD asks the RD to “teach them to carb count”) Current research at the BDC including a brief carb counting quiz Youth with Diabetes Do Not Meet Dietary Goals (Mayer-Davis, JADA, ’06:689-97) Figure. Percent of male and female youth with diabetes who meet dietary recommendations: SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth participants in the dietary assessment protocol, prevalent 2001 and incident 2002. *P<0.01 for comparison of males vs females, adjusted for clinical site, race/ethnicity, and parental education level. (Mayer-Davis, JADA, ’06:689-97) Youth with Diabetes Do Not Meet Glycemia Goals Hvidore Data, Diabetes Care, 2001 Why Carb Count? Need some methodology on which to base rapid-acting insulin dosing with meals/snacks Can allow for more flexibility with eating for people with type 1 diabetes Theoretically, should better match insulin bolus to carb intake and result in reduced post-prandial hyper- and hypoglycemia Why Carb Count? Primary goal of diabetes management is to normalize blood glucose concentrations Both MDI and CSII require patient (or parent) input of CHO to determine proper insulin bolus doses Other methods Sliding scale? Consistent CHO intake Pattern management principles Insulin:CHO ratios Exchange or portion systems GI (glycemic index) and GL (glycemic load) DATA DAFNE study: course teaching flexible intensive insulin treatment combining with dietary freedom and insulin adjustment – Improved A1c at 6 months (9.4% v. 8.4%, p<0.0001) – Improved ‘quality of life’ at one year DCCT: using CHO/insulin ratios in intensively treated group improved glycemic control Factors relating to post-prandial glucose excursions Mismatch of amount of insulin to ingested CHO – Poor CHO counting Failure to account for macronutrient content of ingested food Mismatch of the timing of rapid acting insulin bolus delivery and subsequent insulin action to CHO absorption with resultant post-prandial hyperglycemia Other issues Exercise, post-exercise Rapid-acting insulin dynamics (onset of action, peak action, etc) Location of delivery (subcutaneous, not portal) Psychological factors? Goals Improve understanding of the role of dietary factors and physical activity in glucose excursions Reduce glucose variability for patients/improve quality of life ?Potential application for clinical care now, for closing the loop for an artificial pancreas later? Tips for Carb Counting Benefits of Adjusting Insulin for Carbohydrates Allows More Flexibility – No need to stay within carb ranges for meals – For patients on pump therapy or MDI eating schedule can be much more flexible More Advanced Form of Diabetes Management Potential for more accurate dosing Pump therapy requires carb input Other Considerations Who will be responsible for carbohydrate counting – Parent, child or both Math skills Carbohydrate counting at school – MDI – CSII Focus on Carbohydrate Main nutrient that is converted to blood sugar Emphasize total amount of carbohydrate not the source Carbohydrates are: – – – – Starches- grains, beans, starchy vegetables Fruits Milk and Yogurt Other Carbohydrates (i.e. sweets, desserts etc) Diabetes Food Pyramid Food Labels Locate Serving Size Locate total grams of carbohydrate Rules for fiber and sugar alcohols Starches 15 gm carb servings 1 slice bread 1/2 cup mashed potato 1 dinner roll 1/2 cup corn 1/3 cup cooked pasta, rice or beans Fruits 15 gm carb servings 1 small piece of fruit 1/2 cup (4 oz) juice 1 cup cubed melon 1/2 cup canned fruit, light or juice packed 1/2 cup applesauce, unsweetened Milk and Yogurt 1/2 pint or 1 cup (8 fl oz) milk = 12 gm carb Go Gurt = 13 gm carb Yogurt, light (6-8 oz)= 15 gm carb ½ pint or 1 cup chocolate milk = 25-30 gm carb Resources The Calorie King Calorie, Fat and Carbohydrate Counter- Allan Borushek www.calorieking.com www.diabetesnet.com- Salter 1400 Nutritional scale www.nutritiondata.com- recipe evaluation Text messaging service: Diet1 (34381) Palm pilots Calculating a Dose 3 Step Process 1st Step: Insulin to Carb Ratio Determine how much insulin is needed for carbs eaten at meal or snack: Count up total carb grams Divide total grams by ratio Calculating a Dose 2nd Step: Blood Glucose Correction Determine How Much Insulin is Needed to correct blood sugar (bg) to target Check bg Calculate insulin amount needed to bring bg into target range (i.e. … 1 unit per 50 over 150- Individualized) 3rd Step: Total Dose = Insulin needed for carbs plus insulin needed for bg Calculating a Dose Insulin to carb ratio = 1 unit per 15 gm carb BG correction = 1 unit per 50 over 150 Carb component: 60gm ÷15 = 4 units Blood sugar correction: 250 -150 = 100 100÷50 = 2 units Total Dose = 4 units + 2 units = 6 units “Smart Pumps”- Do the math for you! How do you determine a ratio and blood sugar correction factor? Rules – 1500 Rule Blood Sugar Correction Factor 1500 divided by TDD = # of points (mg/dl) blood sugar will be lowered by 1 unit of REGULAR insulin – 1700, 1800, 2000 Rule Correction Factor Same principle as above – however for RAPID ACTING insulin Depends on proportion of basal to bolus dose – 500 Rule Insulin to Carb Ratio 500 divided by the TDD For RAPID ACTING insulin How do you determine a ratio and correction factor? Food Records – Time of day meal or snack is occurring – Insulin – type and amount – Blood sugar values Pre-prandial 2 hour post prandial – Food – type and amount – Estimated grams of carbohydrates in individual food items – Activity Poor Food Record Excellent Food Record Examples Excellent Food Record – All food amounts listed – Details about food items – Accurate carb counting – Adequate blood sugar readings, including 2 hour post prandial values Poor Food Record – Patient did not list food amounts – Not enough blood sugar readings and/or no 2 hour postprandial blood sugar readings – Inaccurate carb counting Food Records From food records we can determine: – If the patient is carb counting accurately – An insulin to carb ratio Amount of insulin the patient requires per grams of carbs consumed 2 hour post prandial blood sugars – Effects of exercise – Other potential dose adjustments Challenges to Establishing Ratios Patient is in their honeymoon and/or requires very small amounts of insulin Poor food records Inaccuracy with carb counting Erratic blood sugars Inconsistent activity levels Illness Insulin resistance Carbohydrate Counting in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes (CCAT) Study Franziska Bishop, David Maahs, Gail Spiegel, Darcy Owen, Georgeanna Klingensmith, Andrey Bortsov, Joan Thomas, Elizabeth Mayer-Davis Management of Diabetes in Youth, Biennial Conference of the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes July 12-16th, Keystone, Colorado Introduction CSII and MDI require patient input of carbohydrate amount to determine proper bolus insulin dosing. Pilot study results evaluating the accuracy of carbohydrate counting among adolescents with T1DM are reported. Subjects Adolescents (ages 12-18) seen at the BDC (using insulin-to-carbohydrate ratios at least 1 meal/day) Methods Study Visit Subjects recorded their estimate of portion size, carbohydrate content, and frequency of consumption. Subjects assessed the carbohydrate content for 32 foods commonly consumed by youth. Food presented as food models or actual food in common serving sizes or self-served by subject. Results Study participants: n=48, age=15.2±1.8, HbA1c=8.0±1.0% For each meal, accuracy categorized as “accurate (within 10 g)”, “overestimated (by>10 g)”, “or underestimated (>10 g).” For dinner meals, subjects with “accurate” estimate of carbohydrates had the lowest HbA1c (7.7±1.0%) compared to HbA1c of 8.5±1.2% and 7.9±1.0% for “overestimated,” and “underestimated,” respectively (p=0.04) Results Statistically significant overestimation observed for 15 of 32 foods (including syrup, hash browns, rice, spaghetti, and chips) Statistically significant underestimation observed for 8 of 32 foods (including cereal, French fries, and soda). Results Only 23% (11 of 48) of adolescents estimated daily carbohydrates within 10 g of true amount despite selection of commonly consumed foods. Only 31% (15 of 48) of adolescents estimated daily carbohydrates within 20g/day. What does this mean? If an adolescent is overestimating how much carbohydrates they eat by 17 g at dinner, and they are using a 1:8 carbohydrate ratio, then 2 extra units of insulin are being taken which could result in a low blood sugar. Or . . . An adolescent underestimates the carbohydrates in a given meal by 10 grams, and they are using a 1:5 carbohydrate ratio, then they would take 2 units less than needed likely resulting in a high blood sugar Conclusion Adolescents with T1DM do not accurately count carbohydrates and commonly either over or underestimate carbohydrates in a given meal. The Carbohydrate Counting Quiz . . . Your Turn! 22? 34? Instructions for Carbohydrate Quiz The Answers Label Reading Quiz How well do you do? The Answers