Names, Expectations and Black Children's Achievement

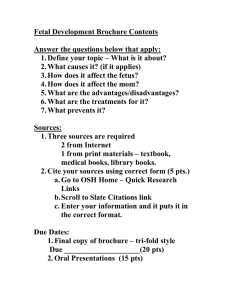

advertisement

Names, Expectations and the Black-White Test Score Gap David Figlio University of Florida and NBER Introduction • Blacks and Whites differ dramatically along a wide range of outcomes • Education is no exception: – Black-White test score gaps exist at the beginning of school – These gaps expand as children get older – No shortage of explanations for this pattern The role of teacher expectations? • Recent experimental evidence (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2004) supports the notion that Blacks are differentially treated in the labor market, even by firms that advertise equal opportunity • Might subtle biases exist among teachers as well? Field evidence from social psychology • Several important studies conducted in the 1970s (Coates, 1972; Feldman and Orchowsky, 1979; Rubovits and Maehr, 1973; Taylor, 1979) • Consistent finding: teachers take Black students less seriously than they do Whites Questions regarding field evidence • Are similar behaviors to the one-time laboratory encounters found in the classroom, with frequent interaction and feedback? • Are results from the 1970s still relevant several decades later? • Presuming that teachers still treat Black children differently in 21st century classrooms, is this differential treatment related to “Blackness” per se, or to some factor like low socio-economic status? Do expectations matter? • Recent work on teacher grading standards (e.g., Betts and Grogger, 2003; Figlio and Lucas, 2004) suggests that high expectations make a difference • Psychology research on teacher perceptions (Jussim et al, 1976) suggests that teacher perceptions impact student outcomes • Key question: Do student-specific factors influence teacher perception/expectation formation? Purposes of this paper • Empirically document the degree to which teachers treat children differently in the classroom • Investigate whether this differential treatment is associated with student outcome differences • Employ a quasi-experimental research design in a large-sample setting that – Reduces the confounding role of unobserved variables – Allows for heterogeneous treatment effects Implementing experimental design on a large scale • Ideal situation would be to randomly assign children to teachers, and follow children from year to year across multiple teachers • Problems with this approach: – Schools don’t do this – Even if they did, non-compliance could dramatically affect estimates (see, e.g., Ding and Lehrer, 2003) An alternative approach: Within-family comparisons • Rather than follow children over time across different settings, instead study children crosssectionally and assume that many of the important unobserved variables (e.g., student motivation or self-concept, family support) are invariant within a household • This is potentially problematic…more in a little while… But… • Isn’t race (or SES) constant within a household? • (Or, put differently: When race is NOT constant within a household, do we honestly believe that the children identified as Black and White within a household are alike on unobservables??) A solution: Names • Recent work in psychology (e.g., Rosenthal, Pelham, Shih) suggests that names influence selfperceptions and others’ perceptions about a person, as well as personal decisions • Considerable within-family variation in the types of names given to children (especially in Black families) • Do teachers form different expectations of Black (and White) children based on their names? Is a name link plausible? • In one large Florida district: – Black-White test score gap increases by 32% from third grade to ninth grade – In third grade, 5% of the gap can be explained by different naming patterns – In ninth grade, 16% of the gap can be explained by different naming patterns – Are these relationships causal?? This paper • Detailed data from a large Florida school district • 164,000 children from 72,000 families, 1994-95 through 2000-01 • For kids born 1989 to present, I merge data with birth certificates, so I have mom’s education, birth weight, labor/delivery complications, prenatal care indicators • Test the hypotheses that – Teachers and administrators expect less from children with Black racially-identifiable names or other names that may connote low socio-economic status – These diminished expectations in turn lead to students performing less well on standardized tests How to measure expectations? • I want to measure expectations based on teachers’ observed treatment of children • However, there are many unobserved variables (such as motivation, self-perception, peer behavior, etc.) that are correlated with observed teacher treatment • My solution: Find two teacher treatment variables that are highly positively correlated, but where an expectations story would have them moving in opposite directions Two measures of expectations • Conditional on test scores, I consider expectations to be low if: – Students are more likely to be “socially promoted” – Students are less likely to be classified as gifted – Promotion and gifted status are EXTREMELY highly correlated, so a prediction of low expectations leading to a divergence in these two outcomes is a very strong one – Importantly, other plausible explanations for outcome patterns (e.g., racial identity explanation) DO NOT suggest that these variables move in opposite directions The problem with sibling comparisons • Of course, you should be concerned that family assignment of names to children is non-random, and transitions in naming patterns may reflect transitions in affluence, segregation, identity, etc. that could affect both names and parenting in ways unobservable to the researcher. Refinement of sibling comparison • I will, in turn, only look at siblings who: – Share the same mother and father – Are born within two years of one another – Are twins (small n) Preview of findings • Children with low-SES names are treated differently from their siblings with more homogenized names at school • They tend to score less on tests than do their siblings What’s in a name? • Linguistic analysis of names led to identification of four attributes of low SES: – – – – Certain prefixes Certain suffixes Presence of apostrophe Combination of long name and exotic consonants used – The more of these attributes present, the more likely that the mother is a high school dropout Attributes of families with certain names The families of children with NO low-SES attributes are: 32% maternal dropouts 57% on Medicaid at time of birth 53% married at time of birth 19% with teenaged mother 41% Black Attributes of families with certain names The families of children with ONE low-SES attribute are: 38% maternal dropouts 68% on Medicaid at time of birth 37% married at time of birth 28% with teenaged mother 62% Black Attributes of families with certain names The families of children with TWO low-SES attributes are: 49% maternal dropouts 86% on Medicaid at time of birth 14% married at time of birth 42% with teenaged mother 96% Black Attributes of families with certain names The families of children with THREE OR MORE low-SES attributes are: 55% maternal dropouts 90% on Medicaid at time of birth 6% married at time of birth 52% with teenaged mother 98% Black Examples of names • • • • • One attribute: Damarcus Two attributes: Da’Quan Three attributes: Da’Nayvious* Four attributes: Da’Qwinzzis* Most popular low-SES name given to Whites: Jazzmyn, Chloe’ and Zakery • Names given to fewer than 10 children and therefore not mentioned explicitly in paper Within-family transitions in names • Among families where the first child had no low-SES name attributes, 12% of succeeding same-sex siblings had a low-SES name • Among families where the first child had at least one lowSES name attribute, 18% of succeeding same-sex siblings had a low-SES name • For Black families, these percentages are 16% and 25% • For families with a high school dropout mother, these percentages are 12% and 19% • Considerable name-mixing exists between first and middle names as well, for the same child! Examples of Black sibling pairs Tras Jennifer Chauncey Christine Fedner Ta’Shikki Tarvel Shanice Gregory Robbyn Casronell Nichole Brandon Rochelle Diijon Quinesha Examples of Black sibling pairs Tras Arthur Jennifer Arneisha Chauncey Chad Christine Sarah Fedner Junior Ta’Shikki Melissa Tarvel Lamar Shanice Gregory Danayvious Robbyn Rudi Sharrick Casronell Antwon Nichole Shavon Brandon Winston Rochelle Ashlee Diijon Jior-dan Quinesha Shimika Name attributes and test scores • Estimated effect of changing names: • Drew to Dwayne: -0.68 pct pts math, -0.74 reading • Dwayne to Damarcus: -1.10 pct pts math, -1.17 pct pts reading • Damarcus to Da’Quan: -0.73 pct pts math, -0.78 pct pts reading • Da’Quan to Da’Qwinzzis: -0.66 pct pts math, -0.70 pct pts reading • Very similar results if count attributes rather than relying on empirical predictions of low SES • Evidence that “Blackness” of a name matters somewhat, but SES of the name matters much more Children born to same father within two years of one another • Estimated effect of changing names: • Drew to Dwayne: -0.52 pct pts math, -0.76 reading (not statistically significant) • Dwayne to Damarcus: -1.00 pct pts math, -1.47 pct pts reading • Damarcus to Da’Quan: -0.66 pct pts math, -0.99 pct pts reading • Da’Quan to Da’Qwinzzis: -0.60 pct pts math, -0.88 pct pts reading The ultimate sibling sniff test: Twins • 616 pairs of twins • Very little exploitable variation in names because of similarity in names given to twins, but there are a few cases of very different names given to twins, e.g., – Lakeisha and Laura – Nicholas and Shanicholas – Monica and Demonica The ultimate sibling sniff test: Twins • Estimated effect of changing names: • Drew to Dwayne: -4.11 pct pts math, -1.81 reading (only statistically significant in math) • Dwayne to Damarcus: -1.77 pct pts math, -3.46 pct pts reading (stat sig in reading) • Damarcus to Da’Quan: -1.20 pct pts math, -2.40 pct pts reading • Da’Quan to Da’Qwinzzis: -1.08 pct pts math, -2.16 pct pts reading Names and teacher expectations: GIFTED REFERRAL • Estimated effect of changing names: • Drew to Dwayne: 0.5 pct pts • Dwayne to Damarcus: -1.9 pct pts (significant) • Damarcus to Da’Quan: -1.3 pct pts • Da’Quan to Da’Qwinzzis: -1.2 pct pts Names and teacher expectations: PROMOTION • Estimated effect of changing names: • Drew to Dwayne: 1.1 pct pts (marginal) • Dwayne to Damarcus: 1.4 pct pts (significant) • Damarcus to Da’Quan: 1.0 pct pts • Da’Quan to Da’Qwinzzis: 0.9 pct pts Teachers, administrators, and peers • School administrators may also be responding to names, and can’t distinguish their responses from teacher responses—but that’s immaterial for my story • Peers may also respond to names, and form friendships and social groups on this basis. I am currently collecting data on the formation of playground friendships, and will address this in future work Asian families as an alternative • Expect signs to flip • Long or Vivek has GPA | test score estimated 0.05 (p=0.21) lower than Asian named Alexander or Charles • Gifted result: 0.11 (p=0.00) higher • Test scores: 4 pct pts (p=0.16) higher • No apparent relationship re: promotion, though this may be because almost no Asian student ever repeats a grade Heterogeneity across schools • I hypothesize that name-based expectations should be less pronounced in schools with – Larger numbers of Black students – Larger numbers of Black teachers Black teachers • The results are stronger in schools with fewer Black teachers: (e.g. Damarcus vs. Dwayne) – Math test score: Few Black teachers: -1.21 (0.56), more Black teachers –0.29 (1.10) – Reading test score: Few Black teachers: -2.03 (0.51), more Black teachers 0.28 (0.95) – Promotion: Few Black teachers: 1.6 (0.7), more Black teachers 0.9 (1.3) – Gifted: Few Black teachers: -2.5 (0.9), more Black teachers –0.2 (1.4) Conclusions • One mechanism through which the widening of the Black-White test score gap over the school cycle occurs may be due to teacher and school expectations—possibly leading to Black children learning less in school • Extra exposure reduces this pattern, and also reduces the likelihood of apparent name-based treatment differences • Results suggestive that teachers are responding to a raceperceived class combination when forming expectations • Role for professional development and teacher training?