Neurology and nutrition

advertisement

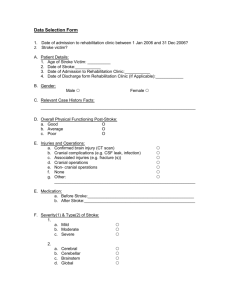

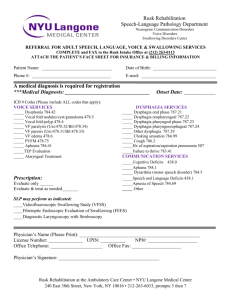

Neurology and nutrition Dr Anhar Hassan, Dr Brendon Boot Senior Neurology Registrar Royal North Shore Hospital Objectives be able to describe the neurological disorders which give rise to dysphagia be able to describe the assessment of dysphagia be able to describe nutritionally relevant stroke risk factors provide or use in the presentation medical terminology and abbreviations for these disorders biomedical parameters and diagnostic tests and how these change with disease progression or improvement medications and other treatments associated with the management of the neurological disorders discussed Neurological disorders resulting in dysphagia Neurology deals with many conditions, affecting the peripheral or central nervous system: Acute, may improve – Stroke Acute on chronic – Multiple sclerosis Progressive – Motor neurone disease – Parkinsons disease – Huntington’s disease Case 1: Mrs J.V. 72 yo lady 2 years progressive weakness initially of upper then lower limbs, later bulbar and respiratory muscles. Diagnosed with motor neurone disease- no treatment to significantly alter disease progression Progressive difficulty walking- now transfers only to and from wheelchair with assistance of her husband. Needs assistance of husband for all activities of daily living Case 1: Mrs JV Noticed soft speech Difficulty swallowing, ineffective cough triggered by food and long periods of time taken for small meals. Drooling a major inconvenience and some “choking” episodes (unpredictable) Marked weight loss- 45 kg at presentation, 5-6 kg loss in the 3 weeks prior to presentation after no oral intake Presented with breathlessness and clinically dehydrated, malnourished and in respiratory failure Mrs JV management Speech therapist assessment - safe for thickened fluid and puree diet, dietitian calculated that her intake would not equal her nutritional requirements Hydrated, receiving all nutritional requirements through percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding tube Discharged with noninvasive ventilator with the aim to use it at night when most desaturations occur and anytime when breathless Discussed end of life decisions again- particularly if unwell Linked in to community palliative care service and motor neurone clinic follow up service Motor neurone disease Degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurones Weakness often asymmetric in legs, hands, proximal arms or oropharynx. No sensory impairment. Usually mentally alert. Respiration is usually affected late. Weight loss occurs from a combination of wasting and dysphagia. Cranial nerve nuclei affected: dysarthria, lingual wasting and fasciculation and impaired movement of the tongue. Dysarthria and dysphagia is caused by upper motor neurone disease (pseudobulbar palsy). The uvula does not move well (or at all) on phonation but a vigorous response is seen in the pharyngeal or gag reflex. MND management 1. 2. 3. 4. Nutrition Ventilation and protect against aspiration Nursing care Medications: No cure – Riluzole (glutamate inhibitor)- prolongs life by 3 to 6 months with no improvement in function or quality of life – Botulinum toxin injections to treat siallorrhea MND multi-disciplinary clinic Assessed as a day stay patient by all members of the team and then follow up arranged in the outpatient clinic via a nursing coordinator Team members: – – – – – – – – Neurologist Respiratory physician Respiratory clinical nursing consultant Physiotherapist Occupational therapist Speech therapist Dietitian Social worker MND prognosis Mean duration of symptoms is 4 years. – Bulbar onset MND is slower to progress Death is usually from respiratory failure, aspiration pneumonia or pulmonary embolism after prolonged immobility. Case 2: Mrs SC 82 year old lady Lives alone following the admission of her husband to a nursing home after his stroke. Supported by a friend. A slowly progressive dementia has been noticed by her friend (aware of people but often forgets recent events) Mrs SC presentation Sudden onset: Hemiparesis (unable to move right side) Global dysphasia- follows 1 step commands unreliably and has fluent but nonsensical speech (conversational “niceties” are reasonably preserved) Noted to be in rapid atrial fibrillation with a small acute myocardial infarction noted on tests. CT brain: dense middle cerebral artery CT brain: loss of grey white differentiation MRI: DWI- L middle cerebral artery territory stroke MRI: T1- L MCA stroke MRI: T2 coronal Mrs SC: progress Aspiration pneumonia noted on day 3 of admission. When first reviewed on arrival (Saturday morning) in emergency she had been “trialled” on a puree diet in the absence of speech therapists to formally assess her till Monday. Food was pooling in her mouth which she seemed unaware of. Cardiac failure ensued with recurrent runs of rapid atrial fibrillation. Medical management was limited by hypotension. Mrs SC: management issues Immediately life threatening – Rapid atrial fibrillation due to hemodynamic compromise and risk of further heart attack. – Heart failure – Aspiration pneumonia Nutrition – Able to have grade 2 thickened fluids. – With the major fluctuations in her other comorbidities, she was not receiving adequate nutrition so additional nasogastric tube feedings were considered. Mrs SC: management issues Preventing further strokes (secondary prevention) – Likely embolic: Anticoagulation (presumed clot from the fibrillating heart) – Exclude other causes (carotid artery disease) – Manage stroke risk factors Functional status after this stroke – Unable to “learn” due to dementia and aphasia. Rehabilitation is not possible. Due to ongoing severe weakness and dependence, she requires nursing home care. – Friend applied for guardianship to organise her affairs Stroke Two types: 1. Infarction (interrupted blood supply) from emboli, unstable atherosclerotic plaques or small vessel disease 2. Haemorrhage secondary to artery weakness (amyloid in elderly, aneurysms etc) and hypertension Stroke Presents with sudden neurological deficit. The distribution of weakness, sensory loss, visual or speech impairment, or neglect depend on the vascular territory involved. Unilateral weakness is characteristic of many syndromes. – eg, Middle cerebral artery territory which affects face>arm>leg weakness to varying degrees and speech if the dominant (usually left) hemisphere is involved Stroke prognosis Death ranges from 8-20% in first 30 days (higher for haemorrhages) Death is mainly from cardiac (AMI, arrhythmias) or respiratory (aspiration pneumonia, pulmonary embolism) sources. Less deaths are due to brain swelling with herniation. Dysphagia in stroke 27-50% of stroke patients have dysphagia 50% of these die or recover spontaneously Dysphagia causes increase risk of chest infections, malnutrition, increased length of hospital stay and readmission to hospital. Medical screening for dysphagia: sip test If constantly alert, position patient in upright position Give 50 ML water in 5 ml steps Listen to patient’s voice and watch for cough between sips – If coping with above, may have thin fluids and appropriate diet – If drowsy or if signs of aspiration, patient “fails” and has formal speech path review of swallowing Dysphagia in stroke Nasogastric tube feeding - easy, quick, relatively noninvasive and safe. Patients can pull them out; nasal ulceration limits duration. PEG - invasive procedure (complications peritonitis, bleeding, perforation of abdominal organs). In the long term, they are more comfortable. FOOD trials Underweight patients had increased mortality (OR for undernourished compared with normal, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.34 to 2.47) Adding oral protein-energy supplements to standard hospital diet was not powered to show a significant benefit Early (<1 week) versus late (>1 week) enteral feeding resulted in an absolute reduction in mortality of 5.8% (95% CI 0.8-12.5, p=0.09) PEG feeding was associated with increased mortality and poor outcome (p=0.05) Nutritionally relevant stroke risk factors Hypertension – Low salt – Usually requires antihypertensive medication Cholesterol – Measure total chol, HDL (good), LDL (bad), triglycerides – Dietitian consult – In vascular patients, unless contraindicated, we start a statin to lower cholesterol Nutritionally relevant stroke risk factors Diabetes: – Diagnosis Fasting BSL <5.5 mmol/L- no further action required Fasting BSL 5.5-6.9- OGTT required Fasting BSL >7 mmol/L- repeat fasting BSL to confirm – Management Refer to dietitian for diabetic diet, diabetic education unit and endocrine team (may need oral hypoglycemic) Case 3: Ms LP 38 yo lady Presented 9 years ago with R visual disturbance – Delayed R visual evoked response – Dx: optic neuritis 9 months later, had clumsiness of her left limbs – Left cerebellar incoordination noted – Given pulse methylprednisolone (1g 3 days) Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis after MRI, lumbar puncture and visual evoked responses. Ms LP: current issues Subjective breathlessness and neuropathic pain limiting oral intake- presented dehydrated with marked weight loss No objective change in weakness, clumsiness or sensory impairment of her cranial nerves or limbs. Ms LP: Strained voice (combined pseudobulbar and cerebellar dysarthria) Marcus Gunn phenomenon moderate asymmetric R>L limb clumsiness with minimal pyramidal weakness, generalised brisk reflexes, independently mobile. Ms LP: progress Given 3 days IV methylprednisolone Commenced on beta interferon some improvement in the pain, but persistent subjective SOB. Already on gabapentin Respiratory physicians investigating further Aim to decrease frequency of relapses Speech pathology, dietitian, physiotherapy, OT and social worker reviews. Referred to rehabilitation Ms LP: progress Infrequent relapses requiring infrequent steroids, no preventive treatment – Relapses too few to qualify for beta interferon initially Slow functional decline after each relapse however Still living independently but too disabled to work. (previous nanny) Sagittal MRI of spine showing increased signal Axial MRI of spine showing increased signal Axial MRI brain showing acute demyelination The same areas of demyelination months later Multiple sclerosis (MS) A chronic disease most commonly in young adults (peak incidence between 20-30 years old, females) with areas of inflammation and demyelination in the central nervous system. Multiple sclerosis subtypes Two clinical pictures: 1. Relapsing remitting with secondary progressive MSUsually starts as a relapsing remitting course of isolated exacerbations then turns into a chronic progressive, unremitting course. (80% of cases over 10-15 years) 2. Primary progressive MSSymptoms include weakness, sensory disturbance, blurred vision due to optic neuritis, incoordination due to cerebellar involvement, bladder instability from spinal cord disease, and cognitive or personality change. MS treatment Acute relapses are shortened by intravenous methylprednisolone Recurrent relapses may qualify the patient for betaferon therapy which has been shown to decrease relapses Side effects of medications commonly used include: – Baclofen for spasticity- nausea, sedative – Oxybutinin for neurogenic bladder instability- dry mouth, nausea, constipation, abdominal discomfort – Recurrent antibiotics for infections- nausea and diarrhea – Corticosteroids for relapses- osteoporosis – Interferons for prevention of relapses- “flu like symptoms” including nausea, fatigue and depression Dysphagia and nutrition in MS Incidence of dysphagia reported from 3-43% in trials. Diet often limited by fatigue, reduced mobility, and other disabilities affecting meal time efficiency (incoordination or visual impairment) No relationship found between dysphagia and nutritional status in a group of 79 patients with a high incidence of dysphagia (43%). No direct evidence but it is suggested to use dietary supplements (eg sustagen) as an effective means of improving the nutrient intake without impairing appetite for normal foods. PEG feeding is an option also Huntington disease: an example of a neurodegenerative condition Progressive hereditary disorder usually presenting in middle age. Course of disease usually runs over a period of 15 years. More rapid in patients with earlier onset of age. Characterised by: • • • Movement disorder (usually chorea) Dementia Personality disorder Diagnosed by genetic testing No known treatment to alter the course of the disease. Treatment of depression and psychosis important Parkinson disease (PD)another neurodegenerative condition One of many causes of “parkinsonism” (including drugs, other neurodegenerative processes, trauma, tumour, postencephalitic) Degeneration of dopaminergic neurones in the basal ganglia Mean age of onset 55 years Insidious onset, slow progression PD: clinical features Tremor at rest- “pill rolling” Rigidity Bradykinesia- slowed movements, small handwriting, soft speech (hypophonia), loss of facial expressions (hypomimia) and dysarthria Flexed posture and shuffling gait Poor balance and falls- loss of postural reflexes “Freezing” phenomenon Fluctuations increase with disease progression and complexity of medical management- “on” vs “off”, dyskinesias usually peak dose PD: management No treatment has been proven to alter the underlying neurodegenerative process but the mortality rate has dropped 50% since treatment with levodopa Medications: Dopamine precursor (levodopa)- the most commonly used Dopamine agonists (bromocriptine) Dopamine releaser/glutamate antagonist (amantadine) Monoamine oxidase type B inhibitor (selegeline) Anticholinergics (benztropine) Surgery: Ablation Deep brain stimulation Neurology patients can be challenging… Level of consciousness- variability Personality or cognitive impairmentscompliance, information processing Treatments may interfere with nutritiondrug side effects, ventilation Disability limiting access to best options Depression and fatigue are commonundermine motivation Important references Bath PMW et al. Interventions for dysphagia in acute stroke (Cochrane review). The Cochrane library, Issue 1, 2002 FOOD Trial Collaboration. Poor nutritional status on admission predicts poor outcomes after stroke: observational data from the FOOD trial. Stroke. 34(6):1450-6, 2003 Jun Donnan GA, Dewey HM. Stroke and nutrition: FOOD for thought. Lancet. Feb 2005; 365: 729-730. Payne A. Nutrition and diet in the clinical management of multiple sclerosis. The British Dietetic Association 2001. J Hum Nutr Dietet. 14; 349-357.