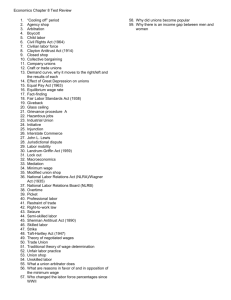

Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors

advertisement

Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Patterns, Current Population Survey, 2002 Union premium averages 21% Pattern by Pattern by Pattern by Hispanics) Pattern by age (rising gap—seniority) gender (gap bigger for women) race (gap bigger for Blacks, skill (gap biggest at low skill) Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Standard rate (straight time) Pay Overtime Premia •Daily overtime included in 93% of agreements •6th or 7th day premia included in 26% of agreements •Holiday pay •Pyramiding (compensation for more than one overtime premium at once) prohibited in 69% of contracts •Most agreements specify how overtime is to be distributed among workers. Mandatory overtime negotiated. Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Piece Rate Pay: Pay for output •Only used where output is easy to measure and verify •Where rate can be agreed upon •Treats workers differently: unions may be uncomfortable •Example Safelite moves from straight time to piece rate Average pay rises Average output (windshields installed per worker per day) rises Quantity vs Quality Standard hour plans •Expected time for a project set. Paid for the job at presumed time. If worker produces at a faster pace, receive a bonus Sears got in trouble for performing unnecessary procedures. Quality vs Quantity again Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Multiple year plans: Raises prorated over time. •Value rises if front-loaded •Value falls if back loaded •Signing Bonuses (pay phased out) COLA (cost-of-living adjustments) •Tie pay increases to the CPI, typical quarterly adjustments •48% of agreements in 1979 •18% of agreements in 2002 •Alternative: wage reopener to reassess only wages if economic circumstances dictate (7% in 2002) Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Profit sharing •10% of plans •ESOPs (Employee Stock Ownership Plans) •Unions are cautious about these, firms favor Scanlon Plans, Gain Sharing •Union and management evaluate ideas designed to lower costs, raise productivity •Proceeds split (75% labor-25% firm typical) Similar to 75/25 split between labor and other factors Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Two-tier wage systems: separate treatment of current, newly hired workers (27% of contracts in 2002) •Used most commonly in declining or threatened firms to preserve compensation for senior workers Low-tier workers view firm low on equity Low-tier workers view union unfavorably Often phased out over time as senior workers retire, economic circumstances improve Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Roll-Up: Many benefits are tied to levels of base pay through percentages •Taxes (Social Security, Unemployment Insurance, Worker’s Compensation) •Pensions •Overtime Premia •Life Insurance •Paid Vacations, … Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Forms of Payment Legal restrictions common across all firms may lower gap somewhat •FLSA (minimum wage, overtime) •ERISA (vesting, pension insurance) •COBRA Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act) Portability of medical insurance •WARN Compensating Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Other Forms of Compensation Pensions (98% of contracts) •Defined Benefit Plan (73%) Guarantees amount paid out, typically as a function of years of service as well as earnings •Defined Contribution Plan (27%) Guarantees amount paid in •Cash Balance Plan (10%) Similar to defined benefit plan except •Reporting includes interest earned as well as the set contribution. Minimum benefit is still guaranteed. •Benefit can be received in a lump sum •Benefit not tied to years of service Compensating Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Other Forms of Compensation Health Insurance (99% of contracts) •Hospitalization (97%) •Prescription drugs (96%) •Physician visits (96%) •Mental health (93%) •Dental (90%) •Vision (73%) •Preferred Provider: Specified services for a guaranteed number of patients. Must select physician from group or pay extra. (74%) •Health Maintenance Organization: Access to specified services at specified institution(s) under direction of a named primary care physician. Specialist services from the group or not covered. (62%) •Fee for Service: Traditional (48%) Compensating Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Other Forms of Compensation Paid Holidays (99%) •May specify rate for employees who work holidays •95% 7+ days, median is 11 Paid Vacations (92%) •2-6 weeks •Plans dictated by regularity of work, production process Graduated: weeks rise with seniority. Most common. Big plants. Uniform: set weeks for all. Manufacturing. Ratio-to-work: Set by intensity of work in previous quarter, year. Transportation Funded: Employer contributes to a pool. Employees draw from the pool during slack work. Construction Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model (Same model for differences in benefits or compensation) Consider two sectors of an industry: U: Union N: Nonunion What would the wage be in the two sectors if labor were freely mobile? Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Consider two sectors of an industry: U: Union N: Nonunion Suppose that workers are equally productive in both sectors In the absence of restrictions on mobility, wages would be equal across the two sectors Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model: What happens to labor in the Union Sector? The Nonunion Sector? Union Wage WU Wage Nonunion WN Demand Demand NU’ NU Employment NN Employment Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Spillover Effect: Displaced labor in the union sector spills over to the nonunion sector Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Spillover Effect Union Wage WU Wage Nonunion WN Demand Demand NU’ NU Employment NN Employment Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Threat Effect: Firms in the nonunion sector raise wages to induce their own workers to resist incentives to unionize Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Threat Effect Union Wage WU Wage Nonunion WN Demand Demand NU’ NU Employment NN Employment Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Wait Unemployment Effect: Displaced labor in the union sector stays in the Union Sector to wait for jobs to open Alternative: Share job loss across NU, each works NU / NU’ Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model Wait Unemployment Union Wage WU Wage Nonunion ? WN Demand Demand NU’ NU Employment NN ? Employment Empirical Tests of Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Wage = Price * Marginal Product = Short-run demand curve Marginal Product = f(Skill, firm attributes) = f(Xi) Empirical Tests of Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Percent differential in the wage approximated by WU – WN = Observed difference At least some of the wage differential will reflect differences in productivity between the U and N sectors (sorting) Suppose that union wages are well explained by the equation WU = a0 + a1* XU WN = b0 + b1* XN Predicted Wage for a nonunion worker if s/he were in a union is WN = a0 + a1* XN Empirical Tests of Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Percent differential in the wage approximated by WU – WN = Observed difference WU - WN = Explained difference WN - WN = Unexplained difference Wage Differentials between Union and Nonunion Sectors Theory: Two –Sector Model:Explained and Unexplained Differences in Wages Union Wage WU Wage Nonunion WU WN WN Demand Demand NU’ NU Employment NN Employment Card, David. “The Effect of Unions on Wage Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 296-315. Card: Table 2: Unadjusted union wage gap rising for men and women Adjusted union wage gap stable (men) or falling (women) Adjusted (explained) gap smaller than Unadjusted (unexplained) gap =>some of union wage effect is sorting on productivity Wage inequality lower for men and women in the union sector (both overall and residual) Wage inequality rising in both the union and nonunion sectors Bratsberg, Bernt and James F. Ragan Jr. “Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (October 2002): 65-83. Bratsberg and Ragan: What is the magnitude of the union wage gap, controlling for differences in productive attributes: WN - WN = Unexplained difference = Adjusted Union Effect Estimates reported in Appendix and Time Path shown in Figure 1 Bratsberg, Bernt and James F. Ragan Jr. “Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (October 2002): 65-83. Bratsberg and Ragan: Appendix: Union Wage Premium by Industry, adjusted for differences in education, experience, gender, minority status, marital status, SMSA, area of country, part-time status, occupational status. Overall, premium varies from 13% to 22% (Consistent with Card) Estimated adjusted premia vary from 2% (textiles, instruments) to 31% (construction), all positive Bratsberg, Bernt and James F. Ragan Jr. “Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (October 2002): 65-83. Appendix: Union Wage Premium by Industry, adjusted for differences in factors. Some downward trend in premium, not dramatic (consistent with Card) Trend effect by industry: 16 falling, 9 significant 16 rising, 9 significant Is there are pattern to which industries are falling wage premia? Figure 1 Falling: Construction, Mining, Wholesale, Retail, Finance Start with high premium Rising:Communications, Durable Goods Start at low premium Reversion to the mean? Figure 2: Variance of union premia across industries Bratsberg, Bernt and James F. Ragan Jr. “Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (October 2002): 65-83. What Factors affect union wage premia over time, across industries? • Business cycles: Union contracts insulate wages from short-term fluctuations Unemployment rate: should raise premium Inflation: should lower premium COLA: adds cyclical sensitivity back in • Deregulation: adds competitors that should lower bargaining power (Laws of Derived Demand) • Import penetration: Union insulates wages at least temporarily • Tests reported in Table 2 Bratsberg, Bernt and James F. Ragan Jr. “Changes in the Union Wage Premium by Industry.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 56 (October 2002): 65-83. Conclusions: • Union wage premia in all industries • Premia becoming more similar across industries over time • Union wages less responsive to business cycles unless tied to inflation through COLAs • Decentralization has mixed effects on wage premia (generally lowers wages for both union and nonunion however) • Union wages more insulated from import competition Belman, Dale L. and Kristen A. Monaco. “The Effects of Deregulation, De-Unionization, Technology and Human Capital on the Work and Work Lives of Truck Drivers.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 502-524. Deregulation has mixed effects on the union wage premium because it lowers wages for both union and nonunion workers. Similarly, import competition may lower wage for both union and nonunion workers, but it lowers wages more for nonunion workers Belman and Monaco document how deregulation has affected union and nonunion wages in trucking Belman, Dale L. and Kristen A. Monaco. “The Effects of Deregulation, De-Unionization, Technology and Human Capital on the Work and Work Lives of Truck Drivers.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 502-524. Between 1935 and 1979 • • • • Entry in trucking routes restricted Rates set bureaucratically Back-hauls banned Some types of freight banned Created monopoly rents, some of which went to union workers These restrictions eliminated with deregulation Deregulation of trucking began in 1979. • Real wages fell by 21% between 1973-1995 • Unionization density in firms whose main business was trucking fell from 55% to 25% Belman, Dale L. and Kristen A. Monaco. “The Effects of Deregulation, De-Unionization, Technology and Human Capital on the Work and Work Lives of Truck Drivers.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 502-524. Table 2: Data on individual trucker earnings between 19731991 Union members earn 28% more, adjusted for skill Holding individual productivity measures fixed, impact of deregulation estimated Impact on Nonunion Union For-hire -0.163 -0.079 Private carriage -0.125 -0.087 Impacts based on sum of coefficients from table 2 =>Deregulation lowered wages for all, but lowered wages less for union members Belman, Dale L. and Kristen A. Monaco. “The Effects of Deregulation, De-Unionization, Technology and Human Capital on the Work and Work Lives of Truck Drivers.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 502-524. Another change in this market: • Communications and location technologies • Routing technologies • Computer technologies Technologies should raise worker productivity— adjust routes to changes in weather, traffic, road construction More efficient back hauls More efficient partial loads Communication without stopping Table 3 shows the use of various technologies by drivers in 1997 Belman, Dale L. and Kristen A. Monaco. “The Effects of Deregulation, De-Unionization, Technology and Human Capital on the Work and Work Lives of Truck Drivers.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 502-524. Belman and Monaco document how these technologies have affected wages • Earnings Satellites raise earnings Dispatchers (old technology) lower earnings • Mileage rates (earnings per mile) Old technologies tend to lower rates per mile; because • Miles Satellite technologies raise miles (reduce wasted time off road; raise hours without raising penalties) Card, David. “The Effect of Unions on Wage Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 296-315. Wage inequality lower for men and women in the union sector (both overall and residual) But…Wage inequality rising in both the union and nonunion sectors Have changes in union density led to rising wage inequality? • Male union density fell from 31% to 19% from 1973 and 1993 • Female union density fell from 14% to 13% Card, David. “The Effect of Unions on Wage Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 296-315. Figures 1 and 2: Changes in union density by gender, skill, and public versus private sector employment • Public sector Male and female density rising Biggest increases at upper tail of skill distribution • Private sector Male and female density falling Biggest decreases at middle or lower end of skill distribution • Potential impact of density changes on inequality different for public, private sectors Card, David. “The Effect of Unions on Wage Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 296-315. Figures 3 and 4: Changes in pattern of union premia by gender, skill, and public versus private sector employment • Wage premia largest for the least skilled for both men and women • Decline in wage premia faster for men as skill increases, (negative for men at highest skills) • Pattern identical between public and private sectors Between 1973 and 1993 Card, David. “The Effect of Unions on Wage Inequality in the U.S. Labor Market.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 54 (January 2001): 296-315. Table 8: Estimate of impact of union density changes on wage inequality by gender, public vs private sectors • Public sector union density rises for men and women Lowers inequality by 1 percentage point for women and men • Private sector union density falls for men and women No impact on inequality among women 1 percentage point increase in inequality among men Decline in union density has had only a small effect on earnings inequality in the united States Buchmueller, Thomas C. John Dinardo and Robert G. Valletta. “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55 (July 2002): 610-627. Percent covered by employer-provided Health Insurance fell from 71% in 1983 to 64.5% in 1997 Unions raise probability of getting benefits How much of the decrease in benefits is due to decline in union density? Buchmueller, Thomas C. John Dinardo and Robert G. Valletta. “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55 (July 2002): 610-627. Do differences in union and nonunion health insurance benefits reflect differences in firm, worker attributes or are they a consequence of union bargaining power? Explained vs unexplained differences in health insurance Buchmueller, Thomas C. John Dinardo and Robert G. Valletta. “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55 (July 2002): 610-627. Table 3: Changes in union effect on health insurance (percent of workers) Observed Adjusted 1997 21.5 17.5 1983 27.4 21.1 => Some of union benefits premium is sorting on productivity => Union effect on benefits falling somewhat Union also raises probability of eligibility (shorter wait to get benefit, gap falling); union raises probability of take-up (higher quality benefits, gap rising) Buchmueller, Thomas C. John Dinardo and Robert G. Valletta. “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55 (July 2002): 610-627. Differences in establishment size Table 5: Union impact on health insurance benefits is biggest in small firms (impact in % of establishments) Virtually all large firms offer benefits If union density had remained constant (especially in small firms) percentage covered by employerprovided health insurance would be 1.6 percentage point higher (25% of decline in employer provided benefits) Adjusted gap is 2.9% Buchmueller, Thomas C. John Dinardo and Robert G. Valletta. “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55 (July 2002): 610-627. Union Impact on benefit quality Table 6: Union impact on firm share of health insurance premium payment Single coverage: Adjusted difference is 9% Family coverage: Adjusted differences is 10% Buchmueller, Thomas C. John Dinardo and Robert G. Valletta. “Union Effects on Health Insurance Provision and Coverage in the United States.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55 (July 2002): 610-627. Union Impact on health insurance benefits for retirees Table 8:Proportion of establishments providing health insurance benefits that also provide benefits to retirees, by union status and establishment size Union gap rising due mainly to decrease in nonunion sector (4.5% in 1988, 14.5% in 1993) (Table 6: CPS data, adjusted, % of employees) Gap exists at all firm sizes, biggest at small firms Loss of union density may affect future retiree health benefits Allen, Steven G and Robert L. Clark. “Unions, Pension Wealth, and Age-Compensation Profiles.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 39 (July 1986): 502-517. Union Impact on pension benefits Table 1:Other things equal Unions raise benefits at retirement by 6%, holding prior earnings fixed Unions lower age at retirement by about 1 year Allen, Steven G and Robert L. Clark. “Unions, Pension Wealth, and Age-Compensation Profiles.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 39 (July 1986): 502-517. Union Impact on pension benefit increase after retirement Table 3: Union pensions grow at a faster rate than nonunion pensions Union effect on pension rises as years of retirement increases (17% for older retirees vs. 5% for youngest retirees) McHugh, Cutcher-Gershenfeld and Polzin. “Employee Stock Ownership Plans: Whose interests do they Serve?” IRRA 49th Annual Proceedings. (1997):23-32. ESOP: Employee Stock Ownership Plans Unions are skeptical • Potential for firm abuse • Potential union replacement by creating community of interest with management Unions have set guidelines for ESOPs: Table 1 McHugh, Cutcher-Gershenfeld and Polzin. “Employee Stock Ownership Plans: Whose interests do they Serve?” IRRA 49th Annual Proceedings. (1997):23-32. ESOP: Employee Stock Ownership Plans Table 4: How do ESOPs differ in unionized firms? Greater labor influence in decisions Share of stock owned by ESOP is bigger More employee participation on Board, design of ESOP Allocation of stock more likely based on hours (equal treatment) Freeman, Richard and Morris Kleiner. “Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 52 (July 1999): 510-527. If Unions raise wages, benefits, do they make firms insolvent? Samuel Gompers “The worst crime against working people is a company which fails to operate at a profit” Freeman, Richard and Morris Kleiner. “Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 52 (July 1999): 510-527. If Unions raise wages, benefits, do they make firms insolvent? Context • Unions raise wages, benefits • Unions raise productivity on average • Gain in wages outweighs gain in productivity Virtually all studies find that unions lower rate of return on assets Lower growth rate of firm Lower stock price • Possible that what unions do is extract rents (excess profits) from firms, do not lower profit below market rate of return, do not threaten firm survival Unions concentrate on larger firms Firms in concentrated industries Freeman, Richard and Morris Kleiner. “Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 52 (July 1999): 510-527. If Unions raise wages, benefits, do they make firms insolvent? Subset of Compustat data (319 firms) with union information added, 1983-1990 Union measures: • Dummy variable if any workers covered by union contract • Percent of workers covered by union contract Table 3: Union impact on profitability • Union presence associated with 3-9 percentage point lower net income on assets (latter is a bit high vs other estimates) • Adverse effect is larger when union density is lower!! Freeman, Richard and Morris Kleiner. “Do Unions Make Enterprises Insolvent?” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 52 (July 1999): 510-527. If Unions raise wages, benefits, do they make firms insolvent? Table 2: NO!!! Probability of insolvency lower for unionized firms Selection effect? Unions target only profitable firms