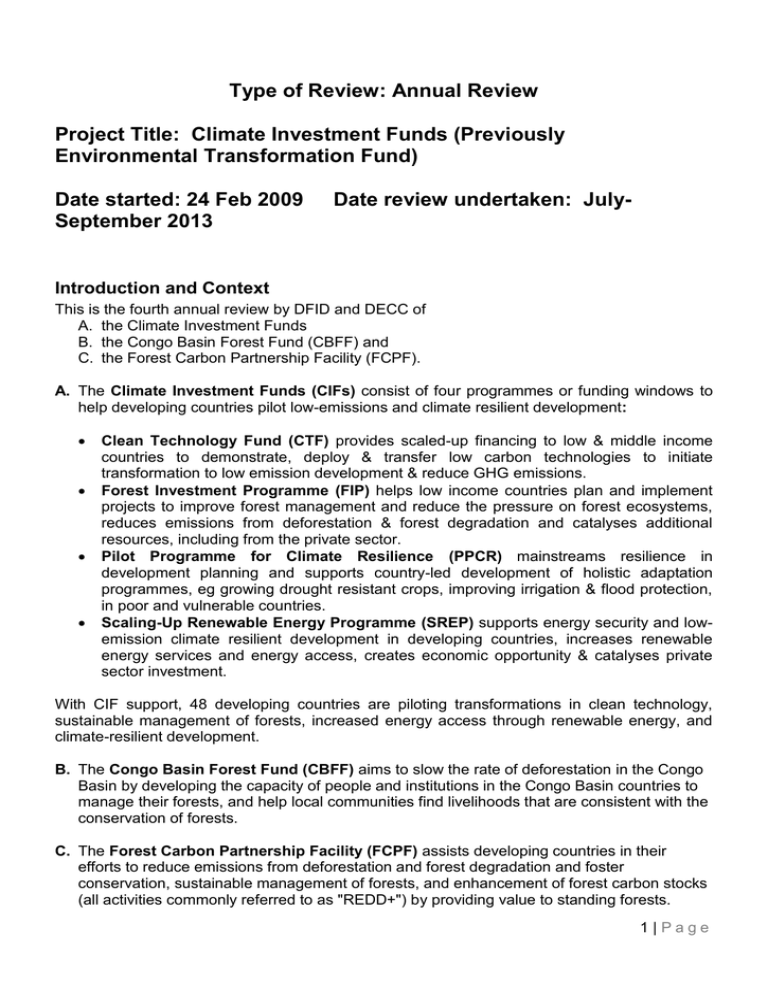

Output 6: The Congo Basin Forest Fund (CBFF) alleviates poverty

advertisement