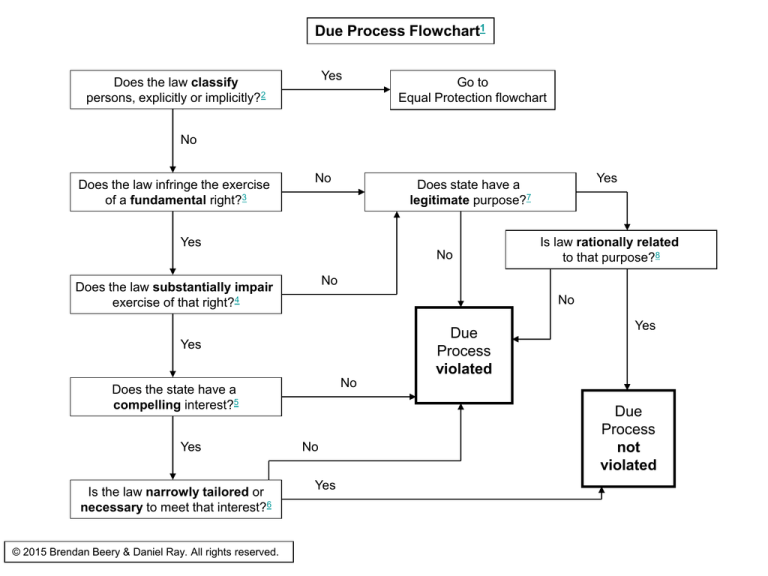

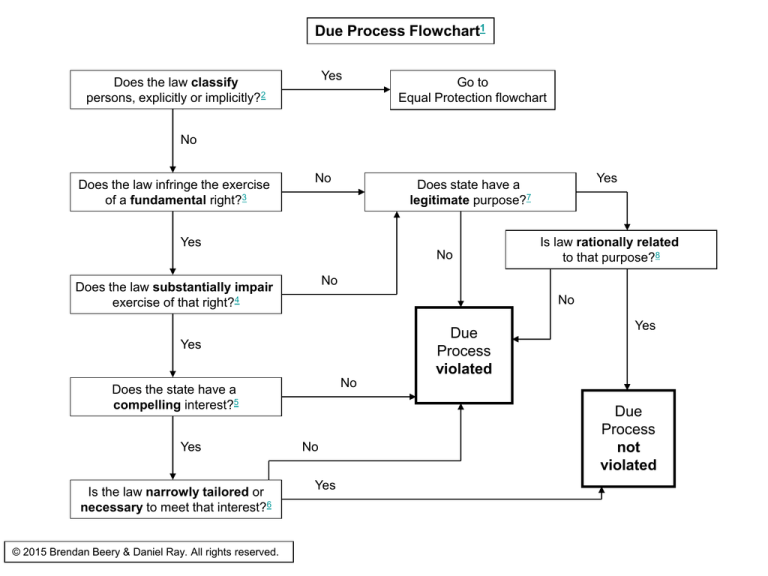

Due Process Flowchart1

Yes

Does the law classify

persons, explicitly or implicitly?2

Go to

Equal Protection flowchart

No

Does the law infringe the exercise

of a fundamental right?3

No

Yes

No

No

Due

Process

violated

Yes

© 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved.

Yes

No

Does the state have a

compelling interest?5

Is the law narrowly tailored or

necessary to meet that interest?6

Is law rationally related

to that purpose?8

No

Does the law substantially impair

exercise of that right?4

Yes

Yes

Does state have a

legitimate purpose?7

No

Yes

Due

Process

not

violated

Notes to Due Process Flowchart

Note 1. This basic due process analysis is used when the government, usually by statute or regulation, interferes

(whether purposefully or not) with the exercise of certain substantive rights. Note, importantly, that this model does

not apply to deprivations of procedural due process. Additionally, some fundamental rights (e.g., the right to

abortion; textual rights) are analyzed using different methodologies. Return to flowchart.

Note 2. If the law does explicitly or implicitly classify persons, then begin with the Equal Protection flowchart to

check for suspect or quasi-suspect classifications. Return to flowchart.

Note 3. The Supreme Court has recognized a variety of fundamental rights in addition to those described in the Bill

of Rights. Those discussed in class include the right to procreate (Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942)); the

right to use contraceptives (Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)); the right to marry (Zablocki v. Redhail,

434 U.S. 374 (1978)); the right to live together as a family (intimate association) (Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S.

494 (1977) (plurality)); and the right to care, custody, and control of one’s minor children (Troxel v. Granville, 530

U.S. 57 (2000) (plurality)). Return to flowchart.

Note 4. See Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374, 387 & n. 12 (1978) (law “directly and substantially” interfered with

fundamental right to marry by making void and criminalizing marriages in violation of law; it absolutely prevented

some from marrying, coerced others into forgoing right to marry, and was a serious intrusion on freedom of choice to

marry even as to those who could comply); but cf. Califano v. Jobst, 434 U.S. 47, 54, 57-58 (1977) (provision in

Social Security Act that decreased monthly benefit by $20 upon marriage was not an attempt to interfere with

marriage decision, even though law might impact beneficiary’s desire to marry or make some possible marriage

partners less desirable than others). Note 4, cont’d. Return to flowchart.

© 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved.

Notes to Due Process Spreadsheet

Note 4, cont’d. See also Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494, 498 (1977) (regulation of family living

arrangements was not an “incidental result” of ordinance); but cf. Bowen v. Gilliard, 483 U.S. 587, 601-03 & n. 17

(that some families might decide to change living arrangements to avoid loss of AFDC benefits does not mean law

was designed or had direct effect of intruding on family living arrangements; Court characterized effect as “indirect”);

Lyng v. Castillo, 477 U.S. 635, 638 (1986) (Food Stamp Act did not “directly and substantially” interfere with family

living arrangements by aggregating household income) (quoting Zablocki). Return to flowchart.

Note 5. The Court has never articulated a test or any comprehensive criteria for deciding whether an alleged

government interest is compelling. The government bears the burden of proving that its interest is compelling.

Return to flowchart.

Note 6. To meet this requirement, the government generally must show that it has used the “least restrictive means

of achieving some compelling state interest.” Thomas v. Review Bd. of Indiana Employ. Sec. Div., 450 U.S. 707

(1981). Return to flowchart.

Note 7. See, e.g., Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 578 (2003) (state has no legitimate interest in criminalizing

sodomy between consenting adults in private setting) (not explicitly applying rational basis review). The government

need not articulate the purpose behind a law. In matters of ordinary social or economic legislation, if the

government does not articulate a purpose for the law, courts are free to assume any legitimate purpose and it does

not matter if such an assumed purpose was the actual purpose for the law. The burden is on the party attacking the

law to show no legitimate purpose. See FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc., 508 U.S. 307 (1993) (equal protection

case). Return to flowchart.

© 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved.

Notes to Due Process Spreadsheet

Note 8. The question here is whether the government sought to achieve its purpose in a patently arbitrary or

irrational way. See United States R.R. Retirement Bd. v. Fritz, 449 U.S. 166 (1980) (equal protection case). A law

that does not implicate fundamental rights is presumed valid, and the court will ask “whether any state of facts either

known or which could reasonably be assumed affords support for” the law. United States v. Carolene Products Co.,

304 U.S. 144 (1938). See also Beach Communications, supra; Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348 U.S. 483 (1955).

Return to flowchart.

© 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved.