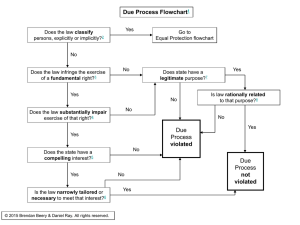

Due Process Flowchart1 Yes Does the law classify persons, explicitly or implicitly?2 Go to Equal Protection flowchart No Does the law infringe the exercise of a fundamental right?3 No Yes No No Due Process violated Yes © 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved. Yes No Does the state have a compelling interest?5 Is the law narrowly tailored or necessary to meet that interest?6 Is law rationally related to that purpose?8 No Does the law substantially impair exercise of that right?4 Yes Yes Does state have a legitimate purpose?7 No Yes Due Process not violated Notes to Due Process Flowchart Note 1. This basic due process analysis is used when the government, usually by statute or regulation, interferes (whether purposefully or not) with the exercise of certain substantive rights. Note, importantly, that this model does not apply to deprivations of procedural due process. Additionally, some fundamental rights (e.g., the right to abortion; textual rights) are analyzed using different methodologies. Return to flowchart. Note 2. If the law does explicitly or implicitly classify persons, then begin with the Equal Protection flowchart to check for suspect or quasi-suspect classifications. Return to flowchart. Note 3. The Supreme Court has recognized a variety of fundamental rights in addition to those described in the Bill of Rights. Those discussed in class include the right to procreate (Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 (1942)); the right to use contraceptives (Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)); the right to marry (Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374 (1978)); the right to live together as a family (intimate association) (Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494 (1977) (plurality)); and the right to care, custody, and control of one’s minor children (Troxel v. Granville, 530 U.S. 57 (2000) (plurality)). Return to flowchart. Note 4. See Zablocki v. Redhail, 434 U.S. 374, 387 & n. 12 (1978) (law “directly and substantially” interfered with fundamental right to marry by making void and criminalizing marriages in violation of law; it absolutely prevented some from marrying, coerced others into forgoing right to marry, and was a serious intrusion on freedom of choice to marry even as to those who could comply); but cf. Califano v. Jobst, 434 U.S. 47, 54, 57-58 (1977) (provision in Social Security Act that decreased monthly benefit by $20 upon marriage was not an attempt to interfere with marriage decision, even though law might impact beneficiary’s desire to marry or make some possible marriage partners less desirable than others). Note 4, cont’d. Return to flowchart. © 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved. Notes to Due Process Spreadsheet Note 4, cont’d. See also Moore v. East Cleveland, 431 U.S. 494, 498 (1977) (regulation of family living arrangements was not an “incidental result” of ordinance); but cf. Bowen v. Gilliard, 483 U.S. 587, 601-03 & n. 17 (that some families might decide to change living arrangements to avoid loss of AFDC benefits does not mean law was designed or had direct effect of intruding on family living arrangements; Court characterized effect as “indirect”); Lyng v. Castillo, 477 U.S. 635, 638 (1986) (Food Stamp Act did not “directly and substantially” interfere with family living arrangements by aggregating household income) (quoting Zablocki). Return to flowchart. Note 5. The Court has never articulated a test or any comprehensive criteria for deciding whether an alleged government interest is compelling. The government bears the burden of proving that its interest is compelling. Return to flowchart. Note 6. To meet this requirement, the government generally must show that it has used the “least restrictive means of achieving some compelling state interest.” Thomas v. Review Bd. of Indiana Employ. Sec. Div., 450 U.S. 707 (1981). Return to flowchart. Note 7. See, e.g., Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558, 578 (2003) (state has no legitimate interest in criminalizing sodomy between consenting adults in private setting) (not explicitly applying rational basis review). The government need not articulate the purpose behind a law. In matters of ordinary social or economic legislation, if the government does not articulate a purpose for the law, courts are free to assume any legitimate purpose and it does not matter if such an assumed purpose was the actual purpose for the law. The burden is on the party attacking the law to show no legitimate purpose. See FCC v. Beach Communications, Inc., 508 U.S. 307 (1993) (equal protection case). Return to flowchart. © 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved. Notes to Due Process Spreadsheet Note 8. The question here is whether the government sought to achieve its purpose in a patently arbitrary or irrational way. See United States R.R. Retirement Bd. v. Fritz, 449 U.S. 166 (1980) (equal protection case). A law that does not implicate fundamental rights is presumed valid, and the court will ask “whether any state of facts either known or which could reasonably be assumed affords support for” the law. United States v. Carolene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144 (1938). See also Beach Communications, supra; Williamson v. Lee Optical, 348 U.S. 483 (1955). Return to flowchart. © 2015 Brendan Beery & Daniel Ray. All rights reserved.