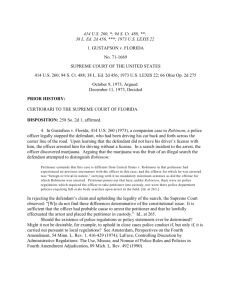

Terry v. Ohio, 392 US 1 (1968)

advertisement