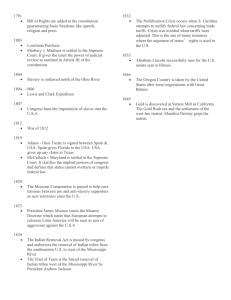

"The Hard Lives and High Suicide Rates of Native

advertisement

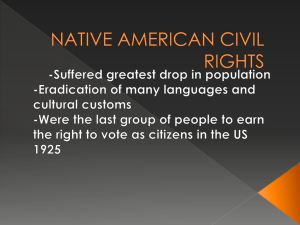

EDITORIAL “The Price of a Slur” by David Treuer The idea of the “Indian giver” has always been deeply ironic, since it’s Indians who have been on the receiving end of some very bad gifts indeed. Last week’s offering from Daniel Snyder, the owner of the Washington Redskins, was only the latest. On March 24, Mr. Snyder announced the creation of the Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation, a charitable organization with the stated mission “to provide meaningful and measurable resources that provide genuine opportunities for Tribal communities.” To date, the foundation has distributed 3,000 winter coats, shoes to basketball-playing boys and girls, and a backhoe to the Omaha tribe in Nebraska. The unstated mission of the Washington Redskins Original Americans Foundation is clear: In the face of growing criticism over the team’s toxic name and mascot imagery, the aim is to buy enough good will so the name doesn’t seem so bad, and if some American Indians — in the racial logic of so-called post-racial America, “some” can stand in for “all” — accept Mr. Snyder’s charity, then protest will look like hypocrisy. In his news release and public statements, Mr. Snyder refers to “our shared Washington Redskins” heritage. To be clear: There is no “our” that includes Mr. Snyder. And there is no “Redskins” that includes us. There has been a sustained effort for decades by activists to change the name of this team and others. Members of my tribe, the Ojibwe, have been a big part of such efforts. But the franchise, valued at $1.7 billion, has a long history of sacrificing decency at the altar of commerce: George Preston Marshall refused to integrate the team until 1962 (the rest of the N.F.L. began doing so in 1946). When the government forced the team to include black players, fans protested outside carrying signs saying “Keep Redskins White!” At stake back then was money (Marshall was afraid that he’d lose fans if African-Americans were on the roster). Money is similarly at stake now. According to Forbes, the Redskins are the eighth most valuable sports franchise in the world. Just consider the merchandise alone. Seldom has the entwined nature of ethics and money and influence been revealed as so unavoidably intestinal in its smell and purpose: to consume the material, to nourish the host and to expel the waste. American Indians — who do not see or refer to ourselves as “redskins” and who take great exception to the slur — are that waste. This isn’t merely symbolic. In 1863, the Cheyenne chief Lean Bear traveled to Washington to protest the government’s treatment of his people. He received a peace medal presented by President Lincoln. He was wearing the same medal when he was gunned down by the United States Cavalry at Sand Creek in 1864. Census data shows that four out of the five poorest United States counties are found within the borders of Indian reservations. So, sure, the gifts of a backhoe and coats are much needed and much appreciated. But gift-giving to Indians rather than systemic change has been an all-too-familiar practice over the centuries, and whether the gifts are beads, backhoes or presidential medals, we know just how much they’re really worth. Mr. Snyder has been quick to point out that he has the support of a handful of those he calls “tribal leaders,” such as the Lower Brule Sioux tribe vice chairman, Boyd Gourneau, and the Pueblo of Zuni governor, Arlen Quetawki, both quoted in the news release. “Tribal officials” might be a better term here than “tribal leaders” because although they are elected, it is in no way clear that they actually represent the sentiments of their constituents any more than John Boehner represents the sentiments of most Americans. These officials’ public-relations-ready comments — “I appreciate your sincerity” and “the entire tribe is so appreciative” — are the diplomatic words of dignitaries, nothing more. It would be a mistake to assume that those words imply democratic consent. The pity that Mr. Snyder seems to feel for Indians and our plight is intimately connected with age-old ideas and images — strength, bravery, a warrior spirit, noble savagery — all of which are conjured by the cartoonish use of Indian names and mascots. We are pitied and feared as Macbeth and Caesar and Achilles are pitied and feared: great but for a fatal flaw (a heel, an ego, ambition). Our tragic flaw, however, is having been subjected to hundreds of years of warfare, colonialism, racism and exclusion. To pay tribute only to brave warriors and pitiful reservations is to engage in a fantasy that erases the lives of real Indians for whom the racial slur “redskins” is intolerable. The name will change. Either the N.F.L. will make Mr. Snyder change the name, or we will. But in trying to buy off that inevitable end, Mr. Snyder has made a terrible mistake in confusing charity with donations. Charity, or caritas, can be defined as an act of generous love. Donations, on the other hand, are material objects for which the owner has no real need and can part with easily and painlessly. What Mr. Snyder has created is not a charity. It is a donation depot. If Mr. Snyder’s hope is that by offering his donations and having them be accepted he has forged a kind of treaty with American Indian tribes — the exchange of coats for the return of good will — he can be sure this is a treaty Indians will break. NEWS ARTICLE “The Hard Lives – and High Suicide Rate – of Native American Children on Reservations” by Sari Horwitz SACATON, ARIZ. The tamarisk tree down the dirt road from Tyler Owens’s house is the one where the teenage girl who lived across the road hanged herself. Don’t climb it, don’t touch it, admonished Owens’s grandmother when Tyler, now 18, was younger. There are other taboo markers around the Gila River Indian reservation — eight young people committed suicide here over the course of a single year. “We’re not really open to conversation about suicide,” Owens said. “It’s kind of like a private matter, a sensitive topic. If a suicide happens, you’re there for the family. Then after that, it’s kind of just, like, left alone.” But the silence that has shrouded suicide in Indian country is being pierced by growing alarm at the sheer number of young Native Americans taking their own lives — more than three times the national average, and up to 10 times on some reservations. A toxic collection of pathologies — poverty, unemployment, domestic violence, sexual assault, alcoholism and drug addiction — has seeped into the lives of young people among the nation’s 566 tribes. Reversing their crushing hopelessness, Indian experts say, is one of the biggest challenges for these communities. “The circumstances are absolutely dire for Indian children,” said Theresa M. Pouley, the chief judge of the Tulalip Tribal Court in Washington state and a member of the Indian Law and Order Commission. Pouley fluently recites statistics in a weary refrain: “One-quarter of Indian children live in poverty, versus 13 percent in the United States. They graduate high school at a rate 17 percent lower than the national average. Their substance-abuse rates are higher. They’re twice as likely as any other race to die before the age of 24. They have a 2.3 percent higher rate of exposure to trauma. They have two times the rate of abuse and neglect. Their experience with post-traumatic stress disorder rivals the rates of returning veterans from Afghanistan.” In one of the broadest studies of its kind, the Justice Department recently created a national task force to examine the violence and its impact on American Indian and Alaska Native children, part of an effort to reduce the number of Native American youth in the criminal justice system. The level of suicide has startled some task force officials, who consider the epidemic another outcome of what they see as pervasive despair. Last month, the task force held a hearing on the reservation of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community in Scottsdale. During their visit, Associate Attorney General Tony West, the third-highest-ranking Justice Department official, and task force members drove to Sacaton, about 30 miles south of Phoenix, and met with Owens and 14 other teenagers. “How many of you know a young person who has taken their life?” the task force’s co-chairman asked. All 15 raised their hands. “That floored me,” West said. A ‘trail of broken promises’ There is an image that Byron Dorgan, co-chairman of the task force and a former senator from North Dakota, can’t get out of his head. On the Spirit Lake Nation in North Dakota years ago, a 14-year-old girl named Avis Little Wind hanged herself after lying in bed in a fetal position for 90 days. Her death followed the suicides of her father and sister. “She lay in bed for all that time, and nobody, not even her school, missed her,” said Dorgan, a Democrat who chaired the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs. “Eventually she got out of bed and killed herself. Avis Little Wind died of suicide because mental-health treatment wasn’t available on that reservation.” Indian youth suicide cannot be looked at in a historical vacuum, Dorgan said. The agony on reservations is directly tied to a “trail of broken promises to American Indians,” he said, noting treaties dating back to the 19th century that guaranteed but largely didn’t deliver health care, education and housing. When he retired after 30 years in Congress, Dorgan founded the Center for Native American Youth at the Aspen Institute to focus on problems facing young Indians, especially the high suicide rates. “The children bear the brunt of the misery,” Dorgan said, adding that tribal leaders are working hard to overcome the challenges. “But there is no sense of urgency by our country to do anything about it.” At the first hearing of the Justice Department task force, in Bismarck, N.D., in December, Sarah Kastelic, deputy director of the National Indian Child Welfare Association, used a phrase that comes up repeatedly in deliberations among experts: “historical trauma.” Youth suicide was once virtually unheard of in Indian tribes. A system of child protection, sustained by tribal child-rearing practices and beliefs, flourished among Native Americans, and everyone in a community was responsible for the safeguarding of young people, Kastelic said. “Child maltreatment was rarely a problem,” said Kastelic, a member of the native village of Ouzinkie in Alaska, “because of these traditional beliefs and a natural safety net.” But these child-rearing practices were often lost as the federal government sought to assimilate native people and placed children — often against their parents’ wishes — in “boarding schools” that were designed to immerse Indian children in Euro-American culture. In many cases, the schools, mostly located off reservations, were centers of widespread sexual, emotional and physical abuse. The transplantation of native children continued into the 1970s; there were 60,000 children in such schools in 1973 as the system was being wound down. They are the parents and grandparents of today’s teenagers. Michelle Rivard-Parks, a University of North Dakota law professor who has spent 10 years working in Indian country as a prosecutor and tribal lawyer, said that the “aftermath of attempts to assimilate American and Alaska Natives remains ever present . . . and is visible in higher-than-average rates of suicide.” The Justice Department task force is gathering data and will not offer its final recommendations to Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. on ways to mitigate violence and suicide until this fall. For now, West, Dorgan and other members are listening to tribal leaders and experts at hearings on reservations around the country. “We know that the road to involvement in the juvenile justice system is often paved by experiences of victimization and trauma,” West said. “We have a lot of work to do. There are too many young people in Indian country who don’t see a future for themselves, who have lost all hope.” The testimony West is hearing is sometimes bitter, and witnesses often come forward with great reluctance. “It’s tough coming forward when you’re a victim,” said Deborah Parker, 43, the vice chair of the Tulalip Tribes in Washington state. “You have to relive what happened. . . . A reservation is like a small town, and you can face a backlash.” Parker didn’t talk about her sexual abuse as a child until two years ago, when she publicly told of being repeatedly raped when she “was the size of a couch cushion.” Indian child-welfare experts say that the staggering number of rapes and sexual assaults of Native American women have had devastating effects on mothers and their children. “A majority of our girls have struggled with sexual and domestic violence — not once but repeatedly,” said Parker, who has started a program to help young female survivors and try to prevent suicide. “One of my girls, Sophia, was murdered on my reservation by her partner. Another one of our young girls took her life.” Stories of violence and abuse Owens recalls how she used to climb the tamarisk tree with her cousin to look for the nests of mourning doves and pigeons — until the suicide of the 16-year-old girl. The next year, the girl’s distraught father hanged himself in the same tree. “He was devastated and he was drinking, and he hung himself too,” Owens said. She and a good friend, Richard Stone, recently talked about their broken families and their own histories with violence. When Owens was younger, her uncle physically abused her until her mother got a restraining order. Stone, 17, was beaten by his alcoholic mother. “My mother hit me with anything she could find,” Stone said. “A TV antenna, a belt, the wooden end of a shovel.” Social workers finally removed him and his brothers and sister from their home, and he was placed in a group home and then a foster home. Both Owens and Stone dream about leaving “the rez.” Owens hopes to get an internship in Washington and have a career as a politician; Stone wants to someday be a counselor or a psychiatrist. Owens sometimes rides her bike out into the alfalfa and cotton fields near Sacaton, the tiny town named after the coarse grasses that once grew on the Sonoran Desert land belonging to the Akimel O’Odham and Pee Posh tribes. She and her friends sing a peaceful, healing song she learned from the elders about a bluebird who flies west at night, blessing the sun and bringing on the moon and stars. One recent evening, as the sun dipped below the Sierra Estrella mountains, the two made their way to Owens’s backyard. They climbed onto her trampoline and began jumping in the moonlight, giggling like teenagers anywhere in America. But later this month on the reservation, they will take on an adult task. Owens, Stone and a group of other teenagers here will begin a two-day course on suicide prevention. A hospital intervention trainer will engage them in role-playing and teach them how to spot the danger signs. “In Indian country, youths need to have somebody there for them,” Owens said. “I wish I had been that somebody for the girl in the tamarisk tree.” SPEECH “MORE THAN MISSIONARIES: WHY NIEA IS HELPING TO BUILD EDUCATION NATIONS AND COMMUNITIES” Dr. Charlotte Davidson Secretary, National Indian Education Association At the Dakota Oyate Challenge Education Conference January 24, 2013 Ya'at'eeh. It is a great pleasure to stand before all of the teachers, school leaders, community members, and families who work so hard to improve education for our children. It is especially wonderful to see our students here today, engaging in sports activities that can help them build the strong character and self-pride they need to succeed in a world that sometimes doesn’t admit they exist. Watching these affirmations of their inherent abilities is amazing. It is great to be here in South Dakota – and not just because NIEA will hold its 44th Annual Convention and Trade Show here this coming October. As the leading advocate for all Native students, NIEA strives to do more than just arrive in a community, stay for a few days, and leave a few gifts behind. That is missionary work, and that is not what NIEA is here to do. NIEA exists to support Native communities build brighter futures for their children, and help them sustain their efforts. Because every Native child is our kin too. NIEA and its members, here in South Dakota and throughout the nation, brings its Advocacy, Research, and Capacity-Building work to every Native community. And our organizations and members stay connected to every community until every child gets the high-quality culturally-based education they need in order to be the future leaders our nations, communities and cultures deserve. We know that far too often, people visit Pine Ridge and other Native communities here in the Great Plains to despair about conditions of education for our Native children. Yet they do nothing while they are there, and leave the children behind never to return. On behalf of my fellow members and leaders, I am here to tell you right now that the work NIEA is doing in every Native community throughout South Dakota and the rest of Plains never leaves our kids behind. Today, I want to talk briefly about NIEA’s goal of building education nation and communities that help our cultures thrive in an increasingly knowledge-based economic future – and what we must all do to make this a reality. When I talk about education nations, I am talking about every child graduating high school ready to attend and complete a two- or four-year degree, an apprenticeship, or a technical school certification. When I think about education nations, I think about every Native student who walks into college walking out with the learning they need to be productive members of their tribes and communities. When my fellow leaders and I envision education nations, we aim for our students to be taught by high-quality teachers who know what they are teaching, who are responsive to the cultures of our children, and are compassionate to every one of them. And when we think about education nations, we see our tribes launching their own schools, our families choosing the schools that best-fit their children, and our communities leveraging new technologies to provide high-quality culturally based learning no matter where our children live. As parents, educators, and advocates for American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children, we have learned a long time ago that educated nations of millions can never be held back. This is because knowledge is the ultimate power. When our children are knowledgeable about their cultures and the world around them, they can build our economies, battle for our languages, and bring about ideas that can save the world. We also know that educated nations can build trails that lead to our tribes and cultures remain relevant beyond our lifetimes. This is because learning is a trail-builder between our past, our present, and our future. When our students get both Advanced Placement classes and language immersion courses, our languages and cultures survive into the next century, and our communities will thrive and not just survive. The reality is that we are only beginning to build our education nations and communities. We are nowhere close to being able to say that every Native child gets an education fit for their future or for that our cultures. At the same time, we know that we can provide every child with effective teaching and high-quality curricula that each student deserves. We have no choice but to make the achievable possible. THE SOBERING REALITY We know all too well the statistics about how poorly our Native students are being educated. Thirty-four percent of American Indian and Alaska Native fourth-graders scored Below Basic in math on the 2011 edition of the National Assessment of Educational Progress. In South Dakota, two out of every five fourthgraders scored Below Basic in math. In an economic future in which math is key to meaningful employment, mathematical illiteracy equals futures of economic despair for our students, their families, and our tribes and communities. The average vocabulary scores for our American Indian and Alaska Native fourth graders declined by five points between 2009 and 2011. On average, an American Indian or Alaska Native fourth-grader had vocabulary scores 16 points – or more than a full grade level lower – than their non-Native peer. We know that our Native students, for whom English is a second language, are not getting the reading help they need for reading literacy. But we aren’t just failing to help our kids learn to read and write. Only one-fifth of American Indian and Alaska Native students surveyed by the U.S. Department of Education two years ago knew "A lot" about their cultures and ways of life. This cultural deprivation, this exclusion of Native languages and ways from our classrooms, is as devastating to our children and communities as efforts to “kill the Indian to save the man” of not so long ago. The consequences of low-quality education that denies that our children come from cultures worthy of being taught in classrooms can be seen in the fact that fewer than three out of every five American Indiana and Alaska Native high school freshmen in Bureau of Indian Education Schools and public schools in nine states – including South Dakota – graduated on time. Two in five. Every hour, the crisis that grips Native education renders our children unable to lead our families and tribes into a future in which the mind is the most-important tool for economic and social success. This educational starvation and cultural dehydration of our children hinders their ability to be our future leaders in ways we are just beginning to understand. For example, there is growing collection of evidence suggests that bilingualism, which is a byproduct of Native language immersion, helps children build their executive functions that are needed for problem-solving and other aspects of life. As psychologists Ellen Bialystok of York University and Michelle Martin-Rhee of the Canadian Institute for Health Information determined in a 2004 study, bilingual children were better-able to distinguish and sort out shapes and colors. When our kids struggle in education, they will eventually struggle to stay healthy into adulthood. The average mortality rate for adults who dropped out of high school is three times higher than that for adults who graduated with a bachelor’s degree, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in a 2007 study. Health economists As David Cutler of Harvard University and Adriana Lleras-Muney of UCLA have concluded, four additional years of education equals out to a six percent decrease in one reporting poor health – and reduces the risk of diabetes by 1.3 percentage points. And the greatest consequence is borne by all of us in terms of Native languages and cultures lost to history because our tribes and communities are only half-educated. Seventy-four Native and indigenous languages may disappear in the next decade, according to UNESCO. Just 200 people still speak Hidatsa, a language of my heritage, while only 10 people speak Mandan, another language that is part of my heritage. And Akira, another language that is part of my lineage is “severely endangered”, according to the Endangered Languages Project. Yet even for our Native students who do graduate from high school, they have not gotten the preparation they need for success in traditional four year-universities, community colleges, technical schools, or apprenticeships, the dominant forms of higher education today. Seventy-four percent of American Indian and Alaska Native students in 2010-2011 have never taken an Advanced Placement course even if when they can master the subject. Not so far from here in Sioux Falls, just 1.4 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native students took A.P. courses in the 2009-2010 school year, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Meanwhile our Native students who are heading to higher education aren’t prepared for completion. Just 11 percent of American Indian high-school seniors who took the ACT, a key test of college readiness, scored high enough to be considered ready for success. One in ten. These numbers are unacceptable, especially in a time in which being college-ready isn’t just about being prepared for traditional four-year colleges. It is about brighter futures for our children and our tribes. On average, a young man or woman with the education they need to get into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields will earn $500,000 more in their lifetime than their peers. That is $500,000 in additional lifetime resources for the betterment of our communities. This even extends beyond to blue-collar careers that provide resources to our communities. A Native student with strong math skills and knowledge of computer languages such as C can become a machine tool-and-die maker shaping the very metal parts used on our cars, earning wages of more than $60,000 a year. We all know the consequences tribes and communities know these consequences all too well. When you look at the high levels of unemployment, the atrociously high rates of suicide among our teens, and the high levels of disease, it can be traced back in part to how our children struggle educationally. Our children need education that nurtures both their minds and their souls. THE STRUGGLE FOR RESOURCES There are several reasons why our Native children are not getting high-quality education. You have all heard about the fiscal cliff, the consequences of sequestration-related budget cuts temporarily averted earlier this month after congressional leaders and the Obama Administration agreed to end their stalemate over federal spending. But for our communities, cuts in spending have been the norm for quite some time. Federal funding for BIE, for example, declined as a percentage of the federal budget by one-third between 1995 and 2011. A freeze imposed 18 years ago on Johnson O’Malley funding – which limits funding to tribes based on their enrollments at that time – has forced schools to stretch scarce funding across more students. The federal government has long failed to live up to its trust obligation to our tribes and communities. This isn’t just a matter of funding. When it comes to education policy, our tribes deserve the same status as state education agencies and school districts. Yet until recently, our tribes could not access education data on the children they are charged with educationally supporting on their paths to adulthood. The federal government, along with states, has ignored their obligations to consult with tribes and communities on the direction of Native education. The most-recent example of this is the Obama Administration’s move to grant waivers from accountability provisions of the No Child Left Behind Act to 34 states and the District of Columbia. While No Child may have not been perfect, the law brought visibility to the lack of educational opportunities for our Native students. But now, thanks to the waivers, we will lose data on how well our children are being educated. We also know that in several states, including South Dakota, there was no evidence that tribes were consulted on waiver proposals before they were submitted for federal approval. But it isn’t just about the federal government. One of the realities our Native children face is that because they are often among the poorest children in the United States, they are often not provided the high-quality teaching they need for success. This is critical because as we all know – and has been demonstrated by decades of evidence – the quality of teaching is the most-important factor in the success or failure of schools to help all students learn. Our Native students also find themselves taught by those who have not been trained to understand their cultures, and in fact, do not always respect their traditions. The lack of cultural competence training has been as damaging to our students as the lack of updated textbooks. Meanwhile our Native communities have been denied the ability to play strong roles in directing the education of our children. More than 40 years after the passage of the Indian Education Act, state and local education officials don’t fully understand the importance of Native communities as lead partners in directing student learning. Especially as states play a more-prominent role in Native education, we must advocate strongly for the rightful recognition of our tribes and communities as the most-important players in improving education for the children we love. Then there is the matter of building the capacity of Native communities to direct and control student learning. This includes exploring new opportunities for reforming Native education. We cannot help Native children receive high-quality education if we don’t first take the steps to make it possible. STEPS TO BUILDING EDUCATION NATIONS AND COMMUNITIES We know this to be true: When Native children are taught by highly effective and culturally competent teachers, they are more-likely to be successful academically. When Native children learn in culturally responsive and nourishing school cultures, they are more-likely to stay on the path to high school graduation, college completion, and economic sustainability. When Native communities direct student learning, we help ensure that our children are prepared to keep our cultures and languages alive for generations to come. And when we take the steps needed to make all these things happen, we are building education nations that can survive and thrive for generations to come. This starts with recognizing that we are not just reforming education for only American Indian, or Alaska Native, or even Native Hawaiian children. We are working to improve education for all Native children. As Natives, we share a common struggle even amid the differences in our cultures and histories. Whether our ancestors were forced onto the Trail of Tears, or suffered through the overthrow of an independent Hawaiian government, all of our peoples have all been subjected to education policies and practices that aim to render our children and communities invisible and uneducated. This common goal of giving our children education worthy of them and our communities is why NIEA represents every Native and all Natives. Whether we are in Huron or in Honolulu, we are all part of a common movement to reform Native education and be the lead decision-makers in the schools and systems that serve our children. When we stand together to build education nations, no one can hold us back. So everyone in this room should know today that NIEA members everywhere stand with you to help all of our students get high-quality teaching and learning. And we are ready for you to stand with us, both as members of NIEA, and as powerful leaders in educating our children. This includes ensuring that the federal government meets its trust obligation to our tribes. This goes beyond the BIE. Every agency within the federal government – and especially the U.S. Department of Education – must play their roles in supporting our efforts to reform Native education. The Obama Administration recognized this in 2011 when it signed Executive Order 13592, which launched the new White House Initiative on American Indian and Alaska Native education, and started the process of bringing all federal agencies together into improving Native education. Part of reforming Native education includes accepting the role of tribal governments in directing student learning. This is happening in part through the new State-Tribal Education Partnership pilot program, which has provided $4 million in funding so far, is helping tribes build the capacity to administer federal education programs. At the same time, the federal government needs to do more. This includes reauthorizing the Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act, which has provided more than $50 million to Native language immersion programs since it became law seven years ago. It also includes passage of the Native CLASS Act, which will give Native communities stronger roles in shaping education. But we cannot just look to the federal government to help us reform Native education. It also starts with each of us together. We cannot depend on others to do for us what we should do for ourselves. As William Demmert once declared, our first role as educators and parents is to create environments in schools, homes, and communities that stimulate the development of our children. This starts by building the capacity of tribes and communities to provide our Native students with high-quality schools, teachers, school leaders, and curricula. As Native communities, we must take power to play stronger roles in directing the education of our children. This means our tribes and families must be full partners and decision-makers in public schools and BIE schools in order to shape student learning. As researchers such as Anthony Bryk of the Carnegie Foundation have shown, empowered families and communities are one of the five key components to improving schools. We are seeing more efforts on this front. In Utah, for example, Navajo Nation has a partnership with that state’s department of education to access data on the performance of students attending public schools. In Oklahoma, the Choctaw Nation is now partnering with that state on a new tool that allows the tribe to access student data. Native communities must mobilize and advocate at the state and district levels. NIEA is already starting to assist state Native education organizations, as well as work with other advocates and educators on the ground. NIEA wants to know more about how it can help you. E-mail us at NIEA@niea.org , or follow us on Twitter at WereNIEA as well as on Facebook at NieaFanPage to share your ideas. As Native peoples, we must also take advantage of new opportunities to start our own schools. This includes exploring the opportunities allowed under public charter schools, a form of public schooling under which tribes and tribal colleges are allowed to either start their own schools or oversee schools launched by those within their communities. Last year, NIEA and Harvard University Graduate School of Education released a study about practices being pioneered by three charter school serving our Native students. All three schools take different approaches that best fit the contexts in which they are located. But these schools succeed in providing both strong academic content and culturally based curriculum to our students. NIEA is further exploring the opportunities provided by charters and working with tribes and other organizations to help them build the capacity needed to launch their own schools. This will also be one of the areas that NIEA will cover at our upcoming Convention here in South Dakota. Meanwhile we must also work on bringing more highly-effective and culturally competent teachers, especially Native teachers, into our children’s classrooms. This includes working with schools of education – as well as developing our own programs – to improve teacher training. Common Core reading and math standards offer an opportunity to improve the quality of curricula our children are taught. At the same time, we as Native educators must work to ensure that culturally-based curriculum is incorporated into the content. We cannot have standards that ignore our culture and language, and we also cannot ignore the need to provide our kids with strong reading, math and science education. Through a grant with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, NIEA is developing teacher training that will support teachers in meshing Common Core standards and culturally based learning. This important work is one that we are looking to bring to every school serving our Native students. Let us take this time right now to build education nations. Let’s bring our collective energies together to provide our children with education worthy of them. As people united behind to educate the children we love, we can make high-quality education a reality here in South Dakota and every place where our Native children live. Thank you for your dedication to building education nations – and to fighting fiercely for the futures of our Native children. INFOGRAPHIC AND STATISTICS Works Cited Davidson, Charlotte, Dr. "National Indian Education Association." National Indian Education Association. N.p., 24 Jan. 2013. Web. 17 Apr. 2014. Horwitz, Sari. "The Hard Lives and High Suicide Rates of Native American Children on Reservations." Washington Post. The Washington Post, 17 Apr. 2014. Web. 17 Apr. 2014. Schwarz, Susan W. "Adolescents Mental Health in The United States." NCCP. National Center for Children in Poverty, June 2009. Web. 16 Apr. 2014. Treuer, David. "The Price of a Slur." The New York Times. The New York Times, 02 Apr. 2014. Web. 08 Apr. 2014.