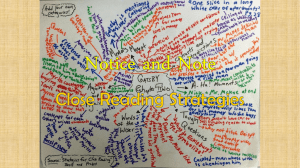

Notice and Note Powerpoint

advertisement

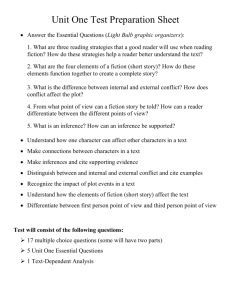

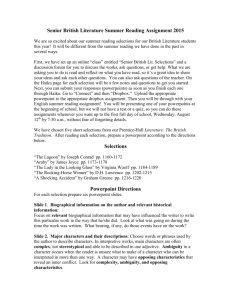

QUOTE FOR THE DAY: “At the end of the game, pawns and kings go back into the same box.” -An Italian Proverb Emerson Grades 6-12 Final After-School Meeting February 6, 2013 AGENDA Announcements: Grimmoire Fairy Tale Writing Contest: Jessica Bennett Note and Notice Book Talk: Barbara Barthel Barbara Barthel and Others Understanding Text Complexity: Barbara Barthel and Bernetta Snell American Lit at Grade 10 or Grade 11?? Bernetta Snell Notice and Note: Strategies for Close Reading Kylene Beers and Robert E. Probst Three Parts 1. The Questions We Pondered 2. The Signposts We Found 3. The Lessons We Teach Introduction: Items of Interest Premise: We want them inside the text, noticing everything, questioning everything, weighing everything they are reading against their lives, the lives of others, and the world around them. Premise: We believe it is the interaction, the transaction, between the reader and the text that not only creates meaning but creates the reason to read. Intro Points of Interest List of the Twenty-Five Most Commonly Taught Novels, Grades 4-8 List of the Twenty-Five Most Commonly Taught Novels, Grades 9-10 Pages 4-5 Final Thought from INTRO: They will need you to put the right books in their hands, books in which they can lose themselves and books in which they can find themselves. Part I: The Questions We Pondered 1. The impact of social networks: Created to help book lovers connect: Shelfari LibraryThing BookCrossing Reader2 Booktribes Revish ConnectViaBooks Part I Reading Habits Survey, Page 14 Also appears in the Appendix Discussion on-screen reading versus primary text reading Another Aspect of the Book At the end of each section, the authors provide a final activity: Talking with Colleagues . . . Great for a book study Great for personal reflection as well Part I Highlights The Role of Fiction The authors promote the POWER of fiction in the classroom: Nonfiction lets us learn more; fiction lets us be more. It seems that not only is it [fiction] a genre with broad appeal, but current reseach shows that it also affects the way we interact with one another. The POWER of Fiction: Contemporary research in psychology and brain functioning confirms the value of fiction in our intellectual and emotional lives, telling us that the effects of reading fiction are far more significant than the mere pleasure of vicarious experiences and the temporary and insignificant release of momentary escape from the present. The humanities, it turns out, do tend to humanize. Part I: RIGOR Rigor is not an attribute of a text but a characteristic of our behavior with that text. Put another way, rigor resides in the energy and attention given to the text, not in the text itself. Part I: Rigor It’s Rigor, Not Rigor Mortis When the text is too tough, then the task is simply hard, not rigorous. The essential element in rigor is engagement. Rigor, in other words, lies in the transaction between the reader and the text and then among readers. The essence of rigor is engagement and commitment. Part I: Intellectual Communities We doubt, no matter how great any standard—common or otherwise—is deemed to be, that any student will arrive in the classroom aching to use detail to support her opinion or rushing to compare and contrast two stories. Part I: Intellectual Communities New standards, without addressing old problems, will not change anything. What might make a difference is to stop teaching students simply to pass a test . . . . What might make a difference would be schools becoming the intellectual communities that they ought to be but can’t be when the penalty for not teaching to the test is so high. Part I: The Role of Talk Suggested reading: Talk About Understanding by Ellin Keene. John Dewey said that the “vital habits” of democracy include “the ability to follow an argument, grasp the point of view of another, expand the boundaries of understanding, [and] debate the alternative purposes that might be pursued. Best developed through TALK. Part I: The Role of Talk The difference between monologic and dialogic talk” Monologic talk is authoritative and presumes that the goal of the listener is to agree with or learn from the speaker. Dialogic conversation expects that the speaker becomes the listener and the listener becomes the speaker, that through give-and take new ideas might emerge, one might change one’s mind when the other is convincing, and the other might reshape an opinion when the first is persuasive. Part I: Role of Talk Asking questions for which you already know the answer is inauthentic, yet that’s the type of questioning that goes on in most classrooms. Research also reveals that in dialogic classrooms, students do more of the questioning, and as a result, achievement increases. Part I: Role of Talk Tips for Improving Student-to-Student Discourse 1. Listen to the conversations in your classroom, asking if there is evidence of rigorous thinking. (Page 33 offers a checklist “Rigor and Talk.”) 2. Step back and let students pose questions. 3. Give various students prompts that can keep the conversation going. 4. Record small-group conversations, using either an audio recorder or video camera. Part I: Role of Talk Tips for Improving Student-to-Student Discourse 5. Give students specific feedback about their comments as a natural part of the conversation. 6. Encourage students to elaborate. 7. Ask high-level questions of all students. 8. Encourage students to use the vocabulary of the discipline. 9. Arrange desks so that students see one another’s faces instead of backs of heads. Part I: What Is Close Reading? Be wary of the generalized concepts of close reading being promoted: Observe what author has presented Avoid imputing to the author anything that is not evident in the text Avoid wandering from experience in the text to think about other experiences Avoid parroting the judgments and interpretations of others for our own assessment Part I: Characteristics of Close Reading It should simply imply that we bring the text and the reader close together. Close reading should suggest close attention to the relevant experience, thought, and memory of the reader; the responses and interpretations of other readers; the interactions among those elements. Part I: Characteristics of Close Reading It works with a short passage. The focus is intense. It will extend from the passage itself to the other parts of the text. It should involve a great deal of exploratory discussion. It involves rereading. Part I: Text-Dependent Questions If you’re in a state that has adopted the Common Core State Standards, you know that the standards “virtually eliminate text-to-self connections” (Gewerts 2012), so the questions you are now to ask about a text are what one architect of the CCSS (and recently named College Board president) David Coleman has dubbed “text-dependent questions.” These are questions the answers to which may be found in the text or deduced from evidence in the text. = MONOLOGIC TALK Part I: Text-Dependent Questions Suggested Reading: Making Meaning with Texts (2005) by Rosenblatt We worry that a focus on text- dependent questions may create a nation of teacherdependent kids. (p. 43) Part I: Letting Students Create Text-Dependent Questions 1. Find a short text that you think might be challenging for your class. 2. Read the selection aloud to students as they follow along or, if appropriate, tell the students to read it on their own. 3. Tell them that as they read they should simply mark those spots where they feel confused, have a question, or wonder about something. 4. Ask them to reread the selection. 5. Pull the whole class back together and collect, on the board or flip-charts, the questions that have been generated. Part I: Letting Students Create Text-Dependent Questions 6. Next, in pairs or trios, ask them to look at the questions they think most interesting or important, discuss them, and make notes about their thoughts. 7. Pull the class back together and work through some of the most interesting questions, asking for the ideas produced by the pairs/trios, and expanding or refining them with contributions from others. 8. Decide what follow-up is needed. Part I: Must Everyone Read the Same Book? The problem isn’t that we ask all students to read the same book. It’s that we expect them to read it in the same way. Also, know that when you have some students reading a book that is not at their instructional or independent reading level (meaning it’s causing them some frustration), then you are not improving their reading fluency. Part I: Must Everyone Read the Same Book? The best way to know if a book is at a student’s frustrational, instructional, or independent level is to do a miscue analysis. Suggested book: Miscue Analysis Made Easy by Sandra Wilde, 2000 Part I: Must Everyone Read the Same Book? We think it’s important [asking a small group or large group of students to read the same novel] because there’s a need for community, for learning to listen to someone else’s opinion, for learning to disagree respectfully, for discovering how to support ideas with reason, for discovering that when you talk with another about a book, you learn more than when you think it through alone. P. 51 Part I: Text Complexity of a Text Most leveling systems are based on numerical analysis of the text. These formulas give information about the vocabulary and the syntax, but nothing about the content. A preferable system takes into account many factors, such as qualitative measures. Part I: Text Complexity Pages 60-61 Worksheet for Analysis of Text Complexity of a Literary Text Part I: Qualitative Dimensions Features “Levels of meaning” refers to the complexity of ideas in a text. “Structure” refers to the design of the narrative or exposition. “Language conventionality and clarity” refers to vocabulary, sentence patterns, style, and register. “Knowledge demands” refers to the experience and knowledge necessary to deal with the text. Part I: Text Complexity of a Text Suggested Reading: Text Complexity: Raising Rigor in Reading by Nancy Frey, Dianne Lapp, and Doug Fisher (2012) Part I: Issues of Text Complexity We finally have to face the fact that the most complex factor in text complexity is the transaction between the reader and the text. Consider: Interest is critical. The student’s background and ability are, of course, also of great importance. In addition to ability and background, you will want to consider the attitudes and maturity of the students. Part I: Text Complexity The concept of text complexity, moving as it does beyond the measurable elements to include attention to qualitative issues and to the connection between reader and text, transfers a great deal of responsibility to the teacher and the media specialist and implies great respect for their judgment. Part II: The Note and Notice Signposts Features that appeared in every young adult novel read by the authors: 1. Contrasts and Contradictions 2. Aha Moment 3. Tough Questions 4. Words of the Wiser 5. Again and Again 6. Memory Moment Part II: Signposts The more students noticed these signposts, the more they were using the comprehension processes: visualizing, predicting, summarizing, clarifying, questioning, inferring, and making connections. Part II: Contrasts and Contradictions This is the point in the novel at which a character’s actions or thoughts clearly contradict previous patterns or contrast with patterns the reader would normally expect, suggesting a change or offering new insight into the character. Part II: Aha Moments These are moments when a character’s sudden insight or understanding helps us understand the plot’s movement, the development of the character, or the internal conflict he faces. Part II: Tough Questions It is the point when the main character—a child or teen—pauses to ask, of himself or a trusted other, tough questions. Part II: Words of the Wiser This is the scene in which a wiser and often older character offers a life lesson of some sort to the protagonists. This lesson often emerges as a theme of the novel. Part II: Again and Again This is the image, word, or situation that is repeated, leading the reader to wonder about its significance. Repetition might provide information about a character, about the conflict, about the setting, or about the theme. Part II: Memory Moment A Memory Moment is a scene that interrupts the flow of the story and reveals something important about a character, plot, or theme. Part II: The Signposts Page 75: Chart The Signposts and Definitions The Clues to the Signpost What Literary Element It Helps Readers Understand Tough Questions Questions a character raises that reveal his or her inner struggles Phrases expressing serious doubt or confusion: “What could I possibly do to . . . ? “I couldn’t imagine how I could cope with . . . ? “How could I ever understand why she . ..? Internal conflict Theme Character development Part II: Anchor Questions Students need to assume ownership of the question. Notes and Notice Bookmark Page 79: Chart of Anchor Questions The Notice and Note Signposts The Question That Follows Why We Ask This Question Contrasts and Contradictions Why would the character act (feel) this way? Contrasts and Contradictions show us other aspects of a character or a setting. This question encourages conversation about character, motivation, or the situation he is in. Part II: Generalizable Language Chart on Page 85. The Signpost Our Generalizable Language To help students think about Contrasts and Contradictions When authors show you a character acting in a way that contrasts with how you would expect someone to act or that contradicts how that character has been acting, you know the author is showing you something important about that character. You’ll want to pause and ask yourself, “Why would the character act this way?” As I think about this questions, I wonder if it might be . . . . Part II: Explaining the Signposts Decide upon an order for teaching the Notice and Note Signposts. Set aside time to teach each signpost lesson. Teach each signpost lesson with a text that illustrates the targeted signpost. Recognize that the model text you choose might be one that is not at a student’s independent reading level. Part II: Explaining the Signposts Use a gradual release model. Think about the generalizable language you will use. And, of course, experiment. Section includes an example classroom situation. Section includes process chart moving from most support to least support. Page 88 Part II: Assessment Assess by listening to their talk Our point is not only that you need to listen to students, but also that you need to listen to them over time. . . . As you listen to students, ask yourself if they . . . Identify the scene that made them think of a signpost? Explain why they think that scene represents that signpost? Move to the anchor question with prompting? Offer more than one speculative answer to the anchor question? Remain open to other speculative answers suggested by classmates? Use evidence from the text to support their answers? Connet this signpost to others (same type or different) in other parts of this novel? Part II: Assessment Assess by Reading Their Logs Notice and Note Reading Log Location Signpost I Noticed My Notes About It Page 2 Contrasts and Contradictions I noticed that everyone had to run just because a plane was flying and that isn’t something I would do. It seemed like a contrast and contradictions lesson where something happens that seems odd. Maybe it was during a war and they were afraid this was Part II: Assessment CCSS Dcoument states, “The Standards do not mandate such things as a particular writing process or the full range of metacognitive strategies that students may need to monitor and direct their thinking and learning. Teachers are thus free to provide students with whatever tools and knowledge their professional judgment and experience identify as most helpful for meeting the goals set out in the Standards.” (NGA,CCSSO 2010, p.4) Part III The Lessons We Teach This section contains a lesson to follow for introducing each signpost to students. APPENDIX In this section, you’ll see many of the figures and templates from Parts I and II, as well as the texts needed to support the lessons found in Part III. All of the texts in this Appendix also appear in dgital format at www.NoticeandNote.com