Acute pancreatitis (Treatment)

advertisement

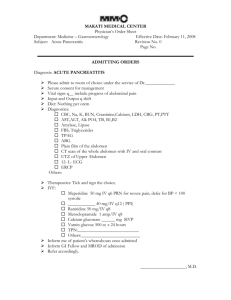

Acute pancreatitis (Treatment) INTRODUCTION 1. 2. 3. Acute pancreatitis can be divided into two broad categories. A. Edematous, interstitial, or mild acute pancreatitis B. Necrotizing or severe acute pancreatitis Treatment of acute pancreatitis is based upon the severity of condition, as determined by clinical, laboratory and severity scoring system. Treatment is aimed at correcting any underlying predisposing factors and at pancreatic inflammation itself. Most attacks of acute pancreatitis are mild with recovery occurring within 5 to 7 days. Death is unusual in such patients. In contrast, severe necrotizing pancreatitis is associated with high rate of complications and significant mortality. 4. 5. 6. A subgroup of patients with severe pancreatitis has early severe acute pancreatitis or fulminant acute pancreatitis characterized by extended pancreatic necrosis with organ failure either at admission or within 72 hours. Early severe acute pancreatitis or fulminant acute pancreatitis has a high mortality of 25 to 30%. An intermediate group of patients with "moderately severe acute pancreatitis", comprised of patients with local complications but no organ failure, has also been recognized. Moderately severe acute pancreatitis has low mortality like mild acute pancreatitis but morbidity (requiring prolonged hospital stay and interventions) similar to severe acute pancreatitis. This topic reviews treatment of acute pancreatitis. Our recommendations are largely consistent with the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines for the treatment of acute pancreatitis. The etiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, methods to predict its severity, and the diagnosis and management of pancreatic pseudocysts are discussed separately. PRETREATMENT ASSESSMENT OF DISEASE SEVERITY 1. The first step in managing patients with acute pancreatitis is determining the severity. The severity of acute pancreatitis can be predicted based upon clinical, laboratory, and radiologic risk factors, severity grading systems, and serum markers. Some of these can be performed on admission to assist in triage of patients, while others can only be obtained after the first 48 to 72 hours or later. Although measurement of amylase and lipase are useful for diagnosis of pancreatitis, serial measurements in patients with acute pancreatitis are not useful to predict prognosis or for altering management. SUPPORTIVE CARE 1. Mild acute pancreatitis is treated with supportive care including pain control, IV fluids, and correction of electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities. The majority of patients requires no further therapy, and recovers and eats within 3 to 7 days. 2. In severe acute pancreatitis, ICU monitoring and support of pulmonary, renal, circulatory, and hepatobiliary function may minimize systemic sequelae. A. Vital signs and urine output should be monitored every few hours in the first 24 to 48 hours. Patients with severe pancreatitis will need ongoing monitoring for other complications that might arise. Sustained hypoxemia, hypotension refractory to bolus of B. IV fluids, and possibly renal insufficiency that does not respond to fluid bolus warrant prompt transfer to ICU for close monitoring. The importance of fluid replacement in the initial stages has been accepted as standard of care. Fluid replacement is important because patients with necrotizing pancreatitis develop vascular leak syndrome. At least one report suggested that inadequate fluid replacement (as evidenced by persistent hemoconcentration at 24 hours) was associated with development of necrotizing pancreatitis. Inadequate hydration can lead to HoTN and ATN. In addition, fluid depletion damages pancreatic microcirculation and results in further pancreatic necrosis. C. D. E. F. Faster initial hydration was associated with decreased mortality. The exact amount and composition of fluid resuscitation that is required has not been extensively studied but several approaches have been published. After initial resuscitation with 20 ml/kg of IVF given over 60 to 90 minutes, approximately 250 to 300 cc of IVF per hour are typically required for 48 hours if cardiac status permits. Adequate fluid replacement can be assessed by improvement in vital signs and urine output and reduction in hematocrit and BUN over 24 hours, particularly if they were high at the onset. Monitoring BUN may be particularly important, as both BUN at the time of admission and the change in BUN during the first 24 hours of hospitalization predict mortality. Increased fluid resuscitation should be considered in patients whose BUN levels stay the same or increase. Fluids should be titrated to maintain urine output > 0.5 ml/kg/hr. However, a low urine output may reflect the development of ATN rather than persistent volume depletion. In this setting, aggressive fluid replacement can lead to peripheral and pulmonary edema without improving the urine output. There is some evidence that fluid resuscitation with lactated Ringer’s solution may be superior to normal saline. In one small RCT of 40 patients, patients who received lactated Ringer’s had significantly lower mean CRP levels compared with patients who received normal saline (52 vs. 104 mg/dL) and significant reduction in SIRS after 24 hours (84 vs. 0%). However, in rare patients with acute pancreatitis due to hypercalcemia, lactated Ringer’s is contraindicated because it contains 3 mEq/L calcium. In these patients normal saline is the preferred fluid for volume resuscitation. H. Oxygen saturation needs to be assessed routinely and supplemental oxygen administered to maintain SaO2 > 95%. Blood gas analysis should be done if SaO2 < 95% or if clinical situation demands. Hypoxia may be due to splinting, atelectasis, pleural effusions, opening of intrapulmonary shunts, or ARDS. Persistent or progressive hypoxia may require mechanical ventilation. Electrolytes should be monitored in patients with acute pancreatitis based on disease severity. Hypocalcemia should be corrected if ionized calcium is low or if there are signs of neuromuscular instability (Chvostek’s or Trousseau’s sign). Low magnesium levels may cause hypocalcemia and should be corrected. Serum glucose levels should be carefully monitored hourly in patients with severe I. pancreatitis and sliding scale insulin should be used to keep blood sugar levels under good control. Hyperglycemia may result from parenteral nutritional therapy, decreased insulin release, increased gluconeogenesis, and decreased glucose utilization, and may increase risk of secondary pancreatic infections. DVT prophylaxis should be considered in bedridden patients. G. PAIN MANAGEMENT 1. Abdominal pain is often dominant symptom. Patients with hypovolemia from vascular leak and hemoconcentration may have ischemic pain. Markers of ischemia include metabolic acidosis and elevated serum lactate. Uncontrolled pain can contribute to hemodynamic instability. A. Attention to adequate fluid resuscitation should be the first priority in addressing severe abdominal pain. B. Adequate pain control requires use of IV opiates, usually in the form of patient controlled analgesia pump. Hydromorphone or fentanyl (IV) may be used for pain relief in acute pancreatitis. Fentanyl is being increasingly used due to its better safety profile, especially in renal impairment. As with other opiates, fentanyl can depress respiratory C. function. It can be given both as boluses as well as constant infusion. The typical dose for bolus regimen ranges from 20 to 50 μg with 10-minute lock-out period (time from the end of one dose infusion to the time the machine starts responding to another demand). Patients on PCA should be carefully monitored for side effects. Meperidine has been favored over morphine for analgesia in pancreatitis because studies showed that morphine caused increase in sphincter of Oddi pressure. However, there are no clinical studies to suggest that morphine can aggravate or cause pancreatitis or cholecystitis. It is important to note that meperidine has short half-life and repeated doses can lead to accumulation of metabolite normeperidine that causes neuromuscular irritation and, rarely, seizures. NUTRITION 1. Patients with mild pancreatitis can often be managed with IV hydration alone since recovery often occurs rapidly, allowing patients to resume oral diet within 1 week. Nutritional support is often required in patients with severe pancreatitis. 2. Nutritional support should be provided to those who are unlikely to resume oral intake for more than 5 to 7 days. N-J tube feeding (using elemental or semi-elemental formula) is preferred to TPN. Early enteral nutrition (24 to 48 hours) should be initiated upon transfer to ICU, development of organ dysfunction, or SIRS persisting for 48 hours if severe acute pancreatitis is confirmed. 3. Enteral A. Enteral feeding is recommended in patients with severe acute pancreatitis. B. C. D. E. A benefit of enteral nutrition is its ability to maintain the intestinal barrier and prevent bacterial translocation from the gut, which may be a major cause of infection. Another advantage is the avoidance of the complications associated with parenteral nutrition including catheter sepsis (which occurs in 2% even if catheter is managed appropriately) and less frequent complications such as arterial laceration, pneumothorax, vein thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, and catheter embolism. In patients with a partial gastric outlet obstruction due to inflammation or a fluid collection, a few weeks of enteral feeding allows for the inflammation to subside or the fluid collection to mature and be drained, leading to resolution of the obstruction and resumption of oral feeding. Consistent with previous meta-analyses, a 2010 meta-analysis of eight trials demonstrated that enteral nutrition significantly reduced mortality, MOF, systemic infections, and need for surgery compared with those who received parenteral nutrition. Radiologic or endoscopic placement of jejunal feeding tube beyond the ligament of Treitz and enteral feeding should be attempted. If this is not possible, NG feeding has been proposed as an easier alternative. A controlled trial comparing nasogastric with nasojejunal feedings found no significant differences in APACHE II score, CRP measurement, pain levels, or analgesic requirement. However, another small study comparing nasogastric feeding with TPN noted increased pulmonary and total complications in the nasogastric group. Further studies are needed before the nasogastric approach can be recommended. We use high protein, low fat, semi-elemental feeding formulas (Peptamen AF®) because of reduction in pancreatic digestive enzymes. We start at 25 cc per hour and advance as tolerated to at least 30% of the calculated daily requirement (25 kcal/kg ideal body weight), even in the presence of ileus. Signs that the formula is not tolerated include gastric residual volumes > 400 cc (with NG feeding), vomiting (with nasogastric feeding), bloating, or diarrhea (> 5 watery stools or > 500 mL per 24 hours with exclusion of C. difficile toxin and medication-induced diarrhea) that resolves if the feeding is held. The presence of fluid collections or elevated pancreatic enzymes is not necessarily a contraindication to oral or enteral feeding. However, in a subgroup of patients there is clear correlation of pain, recurrence of pancreatitis, or worsening of fluid collections, with feeding, either oral or enteral. These patients often have disrupted pancreatic ducts with fluid collections. Drainage of fluid collections may allow resumption of oral intake. If the fluid collections are not considered suitable for drainage or if the target rate of enteral feeding is not achieved within 48 to 72 hours, supplemental parenteral nutrition should be provided. 4. Parenteral A. Parenteral nutrition should be initiated in patients who do not tolerate enteral feeding. The use of parenteral nutrition as adjunct to enteral nutrition to improve provision of calories and protein to critically ill patients may be harmful according to two studies. The first study was a multicenter trial that randomly assigned 4640 critically ill adults who were already receiving enteral nutrition to have supplemental parenteral nutrition initiated early (within 48 hours of ICU admission) or late (after the eighth day of ICU admission). Those who received early parenteral nutrition were more likely to develop a new infection and had a longer duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU stay, and hospitalization. The second study was an observational study that compared three groups: enteral nutrition alone, enteral nutrition plus early parenteral nutrition, and 5. enteral nutrition plus late parenteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated critically ill adults. Enteral nutrition plus either early or late parenteral nutrition was associated with increased mortality compared with enteral nutrition alone. Initiation of oral feeding A. When to begin oral feedings depends on the severity of pancreatitis. B. In mild pancreatitis, in the absence of ileus, nausea or vomiting, oral feeds can be initiated as soon as the pain starts improving and narcotic requirements are decreasing. This usually occurs 24 to 48 hours after the onset of pancreatitis. Traditionally, patients have been advanced from clear liquid diet to solid food as tolerated. More recent data suggest that early refeeding when patients are subjectively hungry, regardless of resolution of abdominal pain and normalization of pancreatic enzymes, may be safe. In addition, starting first with a solid, low fat diet may also be safe, although it does not necessarily decrease length of stay. C. In moderate to severe pancreatitis, oral feeding is frequently not tolerated due to postprandial pain, nausea, or vomiting, probably related to gastroduodenal inflammation and/or extrinsic compression from fluid collections leading to gastric outlet obstruction. Patients are generally placed on enteral or parenteral feeding as discussed above. When local complications start improving, oral feeds are initiated and advanced as tolerated. INFECTION 1. The occurrence of pancreatic infection is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Approximately 33% of patients with pancreatic necrosis develop infected necrosis. Patients who develop infection tend to have more extensive necrosis. Although infection can occur early in the course of necrotizing pancreatitis, it is more often seen late in the clinical course (after 10 days). 2. 3. 4. The important organisms causing infection in necrotizing pancreatitis are predominantly gut-derived, including E. coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella, and Enterococcus. The majority of infections (about 75%) are monomicrobial. Fungal infection and infection with GPC are uncommon but occur more frequently in the setting of prophylactic antibiotic use for severe acute pancreatitis, especially when used for > 10 to 14 days. Fungal infections occur in 9% of necrotizing pancreatitis and it is not clear if they are associated with higher mortality. Approaches taken to decrease bacterial infections in acute necrotizing pancreatitis include enteral feeding, systemic antibiotics, percutaneous CT guided aspiration, and necrosectomy. Our approach based upon these data is summarized in the following algorithm. Prophylactic antibiotics A. Although this is still an area of debate, in the author's practice, we initiate antimicrobial B. therapy with imipenem/meropenem and continue it for 7 to 10 days if there is necrotizing pancreatitis (involving > 30% of pancreas). Because of risk of fungal superinfection, antibiotics should be stopped after 7 to 10 days unless infection is documented. Given that the data are equivocal regarding a benefit to prophylactic antibiotics, it is also reasonable to withhold antibiotics until there is clinical evidence of infection (fever, leukocytosis) or infection has been demonstrated after sampling the necrotic tissue. We do not routinely recommend prophylactic antifungal therapy with fluconazole. Studies evaluating the benefits and harms of prophylactic antibiotics have produced disparate results. Contradictory results on the use of prophylactic antibiotics may be due to differences in methodological quality, inconsistent presence of organ failure in these studies, differences in antibiotic regimens and feeding used, and lack of data on adverse effects, making direct comparisons difficult. i. One systematic review concluded prophylactic antibiotics decreased mortality in severe pancreatitis, but not the rate of infected pancreatic necrosis. ii. In contrast, a subsequent meta-analysis of seven trials detected no mortality benefit or reduction in the incidence of infected necrosis. iii. Further casting doubt on the benefit of prophylactic antibiotics is recognition that it can be associated with the selection of resistant organisms and the development of fungal infection. C. Guidelines issued by multiple societies also differ in their recommendations. i. The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines do not recommend prophylactic antibiotics. ii. Guidelines from the AGA do not make firm recommendation with regard to prophylactic antibiotics, but note that: "Antibiotic prophylaxis, if used, should be restricted to patients with substantial pancreatic necrosis (> 30% of the gland necrotic by CT criteria) and should continue < 14 days." iii. Guidelines from the Italian Association for Study of the Pancreas recommend antibiotics for patients with CT-proven necrosis D. Whether there is a benefit to a specific class of antibiotics is also unclear. However, the authors suggest imipenem or meropenem for 14 days for patients with proven necrosis based on the following data. i. In RCT, 60 patients with severe acute pancreatitis with necrosis affecting at least 50% of the pancreas were randomly assigned to receive two weeks of pefloxacin, 400 mg twice daily, or imipenem, 500 mg three times daily, within 120 hours of symptom onset. Rates of infected necrosis were significantly lower in patients treated with imipenem as compared with pefloxacin (10 and 34%), although mortality was not significantly different in the two groups. ii. A meta-analysis of five trials showed reduced sepsis and mortality but not a reduction in prevention of necrosis with antibiotics (imipenem or meropenem). 5. However, a subgroup of patients receiving prophylactic imipenem had reduction in infected necrosis. Percutaneous CT-guided aspiration A. CT-guided percutaneous aspiration with Gram's stain and culture is recommended when infected pancreatic necrosis is suspected (clinical instability or sepsis physiology, increasing WBC, fevers). Sterile necrosis does not usually require antibiotics and acute fluid collections do not require therapy in the absence of infection or obstruction of a surrounding hollow viscus. B. Continued conservative management in stable patient allows organization of necrotic fluid collections permitting minimally invasive debridement either by endoscopic or C. percutaneous route to clear necrotic debris. However, if there has been no improvement after 1 week of empiric antibiotics in patient with > 30% pancreatic necrosis and there are clinical signs of infection without another obvious site of infection, we perform percutaneous CT-guided aspiration. We repeat percutaneous CT-guided aspiration if conditions of infection remain and no other source are found. If there is evidence of bacterial infection, we consider performing necrosectomy and change the antibiotics according to culture and sensitivity results. If the aspirated material is sterile, we continue conservative treatment for 4 to 6 weeks. A repeat aspiration in 5 to 7 days may be indicated in patients with signs of systemic toxicity since negative fine needle aspiration does not confidently exclude infection. 6. Necrosectomy A. 7. Indications for necrosectomy include infected pancreatic necrosis and sterile symptomatic pancreatic necrosis with abdominal pain preventing oral intake. Surgical debridement of pancreatic necrosis (necrosectomy) can be accomplished by open surgery or minimally invasive approach (endoscopic or percutaneous radiologic). In RCT, compared to open necrosectomy, a minimally invasive step-up approach consisting of percutaneous drainage followed, if necessary, by open necrosectomy, reduced the rate of the composite end point of major complications or death among patients with necrotizing pancreatitis and infected necrotic tissue. Protease inhibitors A. The role of protease inhibitors in the treatment of acute pancreatitis remains unclear as evidence from clinical trials and a meta-analysis show only marginal benefit in patients with severe pancreatitis. TREATMENT OF ASSOCIATED CONDITIONS 1. In addition to the above treatment for pancreatic inflammation, treatment of acute pancreatitis is aimed at correcting any underlying predisposing factors, such as gallstones and hypertriglyceridemia, and treating complications such as splenic vein thrombosis and abdominal compartment syndrome. 2. Gallstone pancreatitis A. Gallstone pancreatitis requires specific therapeutic considerations, in addition to the above recommendations. In this disorder, obstructive stones in the biliary tract or ampulla of Vater are responsible for pancreatitis. B. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) i. ERCP with papillotomy or surgical intervention to remove bile duct stones may lessen the severity of gallstone pancreatitis. Multiple studies suggest that early endoscopic papillotomy is of benefit in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis. Endoscopic papillotomy is typically accompanied by placement of a plastic biliary stent to decrease the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis, which can occur in a patient who already has gallstone pancreatitis. ii. iii. iv. v. vi. In general, ERCP should be performed within 72 hours in those with a high suspicion of persistent bile duct stones (visible CBD stone on noninvasive imaging, persistently dilated CBD, jaundice or rising liver chemistries). In the absence of cholangitis or high suspicion of persistent CBD stone, early ERCP (within 24 to 48 hours) is controversial. Three meta-analyses and one multicenter study reached different conclusions. Two meta-analyses found that early ERCP in patients without cholangitis did not lead to a significant reduction in the risk of overall complications and mortality regardless of the predicted severity. In another meta-analysis of five prospective randomized trials that included 702 patients, early ERCP reduced complications but not mortality in predicted severe pancreatitis; no benefit was observed in predicted mild pancreatitis. We suggest early ERCP should be performed within 24 to 48 hours if there is concomitant cholangitis, persistently abnormal liver tests, or increasing liver tests (indicating the presence of a stone in CBD). In the absence of persistent bile duct stones, cholangitis, persistently abnormal liver tests, or increasing liver tests, patients with biliary pancreatitis, can undergo ERCP before the cholecystectomy. EUS or MRCP to determine the need for ERCP should be considered in patients in whom the clinical course is not improving sufficiently to allow timely laparoscopic cholecystectomy and intraoperative cholangiogram, pregnant patients, patients with high risk of difficult ERCP (altered surgical anatomy or coagulopathy), or if there is intermediate concern regarding the possibility of retained CBD stone, and the patient is not felt to be a good candidate for cholecystectomy with cholangiogram within the near future. C. Cholecystectomy i. Cholecystectomy should be performed after recovery in all patients with gallstone pancreatitis. Failure to perform a cholecystectomy is associated with 25 to 30% risk of recurrent acute pancreatitis, cholecystitis, or cholangitis within 6 to 18 weeks. The risk of recurrent pancreatitis is highest in patients who have not undergone a sphincterotomy. ii. In patients who have had mild pancreatitis, cholecystectomy can usually be iii. performed safely within 7 days after recovery. In a randomized prospective study of 50 patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis, laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed within 48 hours of admission resulted in a shorter hospitalized stay than one performed after resolution of pain and laboratory abnormalities. On the other hand, in patients who have had severe necrotizing pancreatitis, delaying cholecystectomy for at least three weeks may be reasonable because of an increased risk of infection. Cholecystectomy after sphincterotomy in elderly and sick patients is controversial. iv. 3. If the clinical suspicion of CBD stones is high (in those with persistent or worsening liver test abnormalities or cholangitis), a preoperative ERCP is the best test as there is a high likelihood that therapeutic intervention (sphincterotomy, stone extraction) will be required. On the other hand, if the suspicion of persistent CBD stones is low (if liver tests normalize), an intraoperative cholangiogram during cholecystectomy may be preferable to avoid the morbidity associated with ERCP. MRCP and EUS are other imaging options that can exclude CBD stones. A preoperative ERCP can then be performed only in those with stones or sludge in CBD. Biliary sludge A. Most patients with biliary sludge are asymptomatic. However, biliary sludge is commonly found in 20 to 40% of patients with acute pancreatitis with no other obvious cause. On ultrasound, sludge appears as a mobile, low-amplitude echo that layers in the most dependent part of the gallbladder and is not associated with shadowing. We recommend cholecystectomy in patients who have had episode of pancreatitis and have biliary sludge because of high risk of recurrence. B. Although there are no RCT documenting that intervention in patients with pancreatitis and biliary sludge or microcrystals prevents further attacks of pancreatitis, two studies suggest that biliary sludge can lead to pancreatitis, and that these patients may benefit from intervention. i. In one prospective study of 86 patients with acute pancreatitis of which 31 were idiopathic, 23 (74%) had either biliary sludge on ultrasonography (11 patients) ii. 4. and/or cholesterol monohydrate or calcium bilirubinate crystals on biliary microscopy. Of the 21 patients in whom biliary sludge was the only finding (two patients also had dilated bile ducts when restudied), the 10 patients treated by cholecystectomy or papillotomy had fewer recurrences of acute pancreatitis during follow-up (up to seven years) than the 11 untreated patients. Another report evaluated the efficacy of biliary drainage in 51 patients recovering from an attack of acute "idiopathic" pancreatitis. Clusters of cholesterol monohydrate crystals, calcium bilirubinate granules, and/or calcium carbonate microspheroliths were found in 67%. Examination of the gallbladder bile at cholecystectomy or serial ultrasonography of the gallbladder for up to 12 months showed that 73% of the patients with unexplained pancreatitis had biliary sludge or microlithiasis. Dissolution of gallstones by ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) or cholecystectomy prevented further attacks, while those with a delay in surgery or failed UDCA therapy continued to have episodes of pancreatitis. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis A. The treatment of hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis is discussed separately. 5. 6. 7. Hypercalcemia A. Hypercalcemia is a rare cause of acute pancreatitis. If present, treatment should be directed at normalizing serum calcium levels and determining the underlying etiology. It is important to note that Lactated Ringer’s solution is contraindicated in patients with hypercalcemia because it contains 3 mEq/L of calcium and normal saline is the preferred fluid for volume resuscitation. Splenic vein thrombosis A. Splenic vein thrombosis is seen on imaging in up to 19% of patients with acute pancreatitis. B. Treatment should focus on the underlying pancreatitis since the effective treatment may be associated with spontaneous resolution of thrombosis. Anticoagulation may be needed if there is extension of the clot into the portal or superior mesenteric vein resulting in hepatic decompensation or compromise of bowel perfusion. However, this needs to be considered along with the theoretical possibility of hemorrhage into pancreatic necrosis or fluid collections. C. Complications such as variceal bleeding are uncommon (in contrast to chronic pancreatitis) and thus prophylactic splenectomy is not recommended. Abdominal compartment syndrome A. Patients with severe pancreatitis are at increased risk for intraabdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. Factors that can contribute to abdominal compartment syndrome in patients with acute pancreatitis include tissue edema from B. C. aggressive fluid resuscitation, peripancreatic inflammation, ascites, and ileus. Abdominal compartment syndrome is a life threatening complication that results in visceral organ ischemia and tissue necrosis. Abdominal compartment syndrome occurs when intra-abdominal pressure rises above 21 mmHg. Patients in the ICU should be monitored for potential abdominal compartment syndrome with serial measures of urinary bladder pressures. Most patients who develop abdominal compartment syndrome are critically ill and unable to communicate. The rare patient who is able to convey symptoms may complain of malaise, weakness, lightheadedness, dyspnea, abdominal bloating, or abdominal pain. Nearly all patients with abdominal compartment syndrome have a tensely distended abdomen. Progressive oliguria and increased ventilatory requirements are also common in patients with abdominal compartment syndrome. Other findings may include hypotension, tachycardia, an elevated jugular venous pressure, jugular venous distension, peripheral edema, abdominal tenderness, or acute pulmonary decompensation. There may also be evidence of hypoperfusion, including cool skin, obtundation, restlessness, or lactic acidosis. If abdominal compartment syndrome is confirmed, either percutaneous catheter-based or surgical decompression is indicated. D. In patients with severe pancreatitis who require surgical decompression, this typically requires midline laparotomy. Following decompressive laparotomy, temporary abdominal closure is used until the need for an open abdomen has resolved. The abdomen is then closed primarily, functionally, or using skin grafts. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS 1. Acute pancreatitis can be divided into two broad categories: edematous, interstitial or mild acute pancreatitis and necrotizing or severe acute pancreatitis. Treatment varies depending on the severity of the condition. 2. Mild pancreatitis is treated for several days with supportive care including pain control, intravenous fluids, correction of electrolyte and metabolic abnormalities, and nothing by mouth. The majority of patients requires no further therapy, and recovers and eats within 3 to 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 7 days. In severe pancreatitis, intensive care unit monitoring and support of pulmonary, renal, circulatory, and hepatobiliary function may minimize systemic sequelae. Abdominal pain is often the dominant symptom. Adequate pain control requires the use of intravenous opiates, such as meperidine and fentanyl, usually in the form of a patient controlled analgesia pump. In patients with mild pancreatitis, recovery generally occurs quickly, making it generally unnecessary to initiate supplemental nutrition. Soft diet can be started after resolution of pain. In patients with severe pancreatitis, we recommend attempting to provide early enteral nutrition in the first 72 hours through N-J tube placed endoscopically or radiologically. If the target rate is not achieved within 48-72 hours and if severe acute pancreatitis is not resolved, supplemental parenteral nutrition should be provided. The occurrence of pancreatic infection is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in acute necrotizing pancreatitis. We suggest prophylactic imipenem or meropenem in patients with necrosis that involves more than 30% of the pancreas. However, not all guidelines recommend the routine use of antibiotics and it is reasonable to withhold antibiotics unless there is clinical or microbiologic evidence of infection. We suggest the following algorithm, based upon clinical and CT findings, to direct percutaneous aspiration, antibiotic therapy, and minimally invasive or open surgical debridement as needed. In patients with gallstone pancreatitis, we recommend early ERCP and sphincterotomy for those who have a high suspicion of cholestasis and those with cholangitis. Cholecystectomy should be performed after recovery in all patients with gallstone pancreatitis.