Primary Care Practice

advertisement

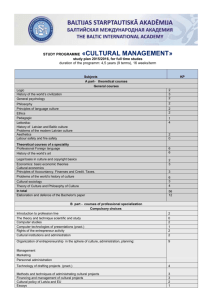

Primary Care Practice: Surprise & Uncertainty Benjamin F. Crabtree UMDNJ-RWJMS Dept Family Medicine Overview Translating evidence into practice Results from two studies of family practices Practices as complex systems Implications of complexity science for managing uncertainty 1000 persons 800 report symptoms 327 consider seeking medical care 217 visit a physician’s office (113 visit a primary care physician’s office) 65 visit a complementary or alternative medical care provider 21 visit a hospital outpatient clinic 14 receive home health care 13 visit an emergency dept 8 are hospitalized <1 is hospitalized in an academic medical center Fig. Results of a reanalysis of the monthly prevalence of illness in the community and the roles of various sources of health care. (Green LA et al., N Engl J Med 2001, 344:2021-2024) Background Recent advances in diagnostic and treatment technologies have produced great opportunities to decrease morbidity and mortality from many common diseases. Clinical trials and evidence-based reviews have established widely accepted clinical guidelines for the management and prevention of diseases. The Uncertainty & Surprise Dissemination of these advances into clinical practice has been disappointing, resulting in disparity between scientific evidence and actual practice. There is an ongoing onslaught of new information and technology resulting in the need for continual learning in practice. Current models of organizational change limit change in clinical practices and do not anticipate uncertainty. Dissemination Strategies Continuing medical education Evidence-based guidelines Opinion leaders Audit and feedback Incentives & disincentives Academic detailing Patient and/or consumer activation Office system innovations Continuous quality improvement Difficulty with current approaches Each has demonstrated some success under certain circumstances, but none is effective in a generalizable manner. Combination of approaches are more effective than individual approaches. Each assumes that physician and practice change is a linear process and fails to account for the complexity of practice systems. Two Studies of Practices Direct Observation of Primary Care (DOPC) Funded by grant from NCI (1 R01 CA60862) Prevention & Competing Demands in Primary Care (P&CD) Funded by grant from AHRQ (R01 HS08776) Direct Observation of Primary Care Cross-sectional observation of 84 family practices & 4454 patient visits to 138 physicians in Ohio Direct Observation Davis Observation Code Checklists Medical Record Reviews Patient Exit questionnaire Billing Data Practice Environment Checklist Ethnographic Fieldnotes Prevention & Competing Demands In-depth multimethod comparative case study of 18 family practices & 1,600 visits to 56 clinicians in Nebraska Prolonged direct observation of practice environment recorded in checklists and field notes Direct observation of 30 encounters/clinician recorded in checklists and field notes Chart audits of patients who were observed Interviews of all clinicians and most staff Variation in Practice Physicians provide integrated, prioritized care within an ongoing personal relationship. Stange KC, Jaen CR, Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF. The value of a family physician. J Fam Pract 1998; 46:363-368. Services are tailored to meet risk factors, patient preferences, and teachable moments. Jaen CR, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC. Making time for tobacco counseling. J Fam Pract 1998; 46:425-428. Variation in Practice Antibiotics are prescribed inappropriately for acute URI despite evidence. Scott J, Cohen D, DiCicco-Bloom B, Orzano J, Jaen C, Crabtree B. Antibiotics use in acute respiratory infections and the ways patients pressure physicians for a prescription. J Fam Pract, 2001; 50(10): 853-8. Smoking cessation counseling rates of physicians vary considerably. Jaen C, McIlvain H, Pol L, Phillips R, Flocke S, Crabtree BF. Tailoring tobacco counseling to the competing demands in the clinical encounter. J Fam Pract, 2001; 50(10): 859-63. Management of emotional distress varies considerably among physicians. Robinson D, Prest L, Susman J, Rouse J, Crabtree B. Technician, friend, detective, and healer: family physicians’ responses to emotional distress. J Fam Pract, 2001; 50(10): 864-70. Variation in Practice Patient care staff roles in practices often do not match professional training. Aita V, Dodendorf D, Lebsack J, Tallia A, Crabtree B. Patient care staffing patterns and roles in community-based family practices. J Fam Pract, 2001; 50(10): 889. Geographic location of practice influences the delivery of services. Pol L, Rouse J, Zyzanski S, Rasmussen D, Crabtree B. Rural, urban, and suburban comparisons of preventive services in family practice clinics. J Rural Health, 2001; 17(2): 114-121. Practices are complex Forced discontinuity of care results in 24% of patients with managed care insurance changing physicians over a 2 year period, impacting quality of care. Flocke S, et al. The impact of insurance type and forced discontinuity on the delivery of primary care. J Fam Pract, 1997; 45: 129-135. Visits are complex with a large variety of problems & multiple problems/visit that are covered in visits of 10 minute average duration. Stange KC, et al. Illuminating the “black box:” A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract, 1998; 46: 377389. Practice are complex Multiple family members are treated in 18% of visits making visits longer, but with no difference in billing. Flocke S, et al. The effect of a secondary patient on the family practice visit. J Fam Pract, 1998; 46: 429-434. Many patients have emotional distress (19% of patients seeing a family physician) with dramatic differences in time use (10 min no distress vs. 11.5 min distress & no dx vs. 12.8 min distress & dx) Callahan EJ, et al. The impact of a recent emotional distress and diagnosis of depression or anxiety on the physician-patient encounter. J Fam Pract, 1998; 46410-418. How can you make sense of all this variation and complexity? 6 Health System 4 Practice 5 Local Community 1 Patient 3 Clinical Encounter 2 Clinician Practices as Complex Adaptive Systems Practices co-evolve locally with communities to meet the particular needs of patients. Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, Stange KC. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract 1998; 46:369-376. Important features of practices that make them unique: • • • • History and initial condition Particular agents and patterns of nonlinear interaction Local fitness landscape Regional and global influences Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Crabtree BF, Stange KC. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract, 2001; 50(10): 872-8. Three Properties of Complex Systems Self-organization Spontaneous development of structures and forms of behavior according to non-linear interactions among agents seeking a better position in the local fitness landscape. Co-evolution Each system evolves over time in relationship to other systems in the local fitness landscape. Emergence The system that evolves is greater than the sum of its parts and cannot be understood just by understanding the individual parts. Franchise Family Practice Suburban practice created by a hospital system to serve an insured middle-class population. Focus is on providing efficient medical services and maximizing financial success. Internal processes related to patient care, office operations, income generation, and physician style all work towards this focus and related goals. Dusty Garden Family Practice Four physician inner-city practice serving a local indigent population. Vision is to empower its underserved community and to improve the community’s health. Founding physician has strong beliefs about caring for the underserved. Internal processes related to patient care, office operations, preventive service delivery, and physician style all work towards this vision. Observation Intervention DOPC Direct Observation of Primary Care P&CD Prevention & Competing Demands in Primary Care STEP-UP Study To Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice Study To Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice STEP-UP Randomized clinical trial of 80 family practices in Ohio Multimethod assessment (MAP) of values, structures, and processes Crabtree B, Miller W, Stange K. Understanding practice from the ground up. J Fam Pract, 2001; 50(10): 881-887. Tailored change strategies Goodwin M, Zyzanski S, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery. The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). Am J Prev Med, 2001; 21: 20-8. Practice Assessment Methods Direct observation of practice and clinical encounters (2-5 days) • • • • Participant observation fieldnotes Structured and unstructured checklists Chart reviews and billing data Informal and formal interviews Physician, staff, and patient surveys Practice Genogram Practice Genogram McIlvain HE, Crabtree BF, Medder J, et al. Using “practice genograms” to understand and describe practice configurations. Fam Med, 1998; 30:490-6. A MD 1987-89 C MD 1987 Age: 50's B MD 1987-92 F (C's wife) Collections Part time G Head Nurse I Aide Part time G Head Nurse 3 days/week D MD 1990 Age: 40's E MD 1992 Age: 30's H Business Manager promoted 1992 J Old timer L Front Desk 1987 K Aide Part time M Front Desk 4 years H Front Desk 1987-92 N Insurance 5 years O Transcriptionist 4 years Feedback & Facilitation Practice report & genogram generated and shared with practice stakeholders Values, structures, processes, and outcomes shared along with reflection points Negotiated intervention • Instrumental approaches • Motivational approaches Follow-up & facilitation Percent of Eligible Services Up to Date Global Preventive Service Delivery Rates 0.43 0.41 0.39 0.37 0.35 0.33 0.31 0.29 0.27 0.25 Baseline 6 months 12 months Intervention 18 months 24 months Control Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, Ruhe M, Weyer SM, Konrad N,Esola D, Stange KC. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery: The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). Am J Prev Med, 2001; 21:20-8. Implications of STEP-UP Assessments for tailoring interventions to fit local fitness landscapes Facilitate interventions to identify and maximize practice capacity to change Practice and clinician self-reflection for ongoing learning Observation Intervention DOPC Direct Observation of Primary Care P&CD Prevention & Competing Demands in Primary Care IMPACT Insights from Multimethod Practice Assessment of Change over Time STEP-UP Study To Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice ULTRA Using Learning Teams for Reflective Adaptation Emergent Quality Multi-method Assessment Process (MAP)/ Reflective Adaptive Process (RAP): an iterative assessment and reflective change approach that uses complexity science as a conceptual framework to guide the processes. ULTRA NHLBI funded group randomized clinical trial of 60 practices in NJ and PA Intervention focused on interrelationships of key stakeholders (agents) Two week practice assessment (MAP), followed by a practice summary report and 3-6 months of facilitated reflective practice teams (RAP) Outcome measures: smoking screening; management of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma; and practice culture and capacity for change Intervention Overview MAP Collected by facilitator first two weeks in practice Practice information form (Completed by Practice Mgr) General observation & key informant interviews & Documents Practice genogram RAP Based on MAP, facilitator helps identify team leader and members with the goal of diversity among agents Team meets for 1 hour weekly, with initial focus on team skills and collaboration Using MAP assessment as starting point, team identifies problems with system level implications and begins improvement cycle A Last Word From Yogi “In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”