W-2 Suicide Risk Assessment and Management

advertisement

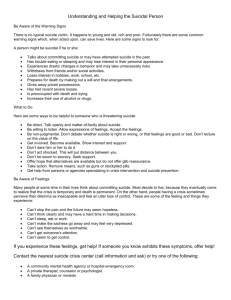

Suicide Risk Assessment and Management Andrew C. Gillespie, PhD, MSW, LISW-S, LICDC-CS Behavioral Healthcare Partners of Central Ohio, Inc. 77 Granville Street Newark, Ohio 43055 1-740-814-0048 andygillespie@bhcpartners.org Captain Ahab from “Moby Dick”, by Herman Melville, 1851. “Walking the deck with quick, side lunging-strides, Ahab commanded the t’gallant sails and royals to be set, and every stunsail spread. The best man in the ship must take the helm. Then, with every mast head manned, the piled- up craft rolled down before the wind. The strange upheaving, lifting tendency of the taffrail breeze filling the hollows of so many sails, made the buoyant, hovering deck to feel like air beneath the feet; while still she rushed along, as if two antagonistic influences were struggling in her – one to mount directly to heaven, the other yawning to some other horizontal goal. And had you watched Ahab’s face that night, you would have thought that in him also two different things were warring. While his one live leg made lively echoes along the deck, every stroke of his dead limb sounded like a coffin-tap. On life and death this old man walked”. Moby Dick, Chapter 51. Suicidal Risk. • “Feeling suicidal is a common experience, dying from this condition is very rare” David Clark (1987). • Suicide and suicidal behaviors have severe consequences, but are statistically rare, even in populations at risk. • Data from suicide hot line statistics estimate that 15 million people yearly experience suicidal ideation, yet the Center for Disease Control reports that approximately 29,000 complete suicide yearly. • Attempts and ideation account for between 0.7% and 5.6% of the population each year, while the annual incidence of suicide in the general population is 10.7 suicides for every 100,000 persons, or 0.0107% of the total population per year. • The statistical rarity of suicide also makes it impossible to predict on the basis of risk factors alone or in combination. • The CDC reports that approximately 750,000 people attempt suicide, and 1 in 25 complete the act (30,000). Recent Rates and What They Tell Us. • United States. • National Average: 11 per 100,000 • Elderly white males (65+): 56 per 100,000 • Elderly black males: 16 per 100,000 • Elderly white females: 2 per 100,000 • Elderly black females: 0 per 100,000 • Adolescent white males: 13 per 100,000 • Adolescent black males: 6 per 100,000 (increasing rapidly) • Native Alaskans: 84 per 100,000 • Law enforcement officers: 9 per 100,000 • College students: 7 per 100,000 • Florida and Arizona has the highest elderly suicide rate. Who is at Risk? “Suicide is the result of an untimely convergence of multiple psychiatric, psychological, social, environmental, occupational, cultural, medical, academic factors that severly challenges an individual’s capacity to cope”. Edwin Schneidman 1954. Three Kinds of Suicide. • Altruistic: to die for a cause, self inflicted death being • • honorable. Egoistic: the individual has too few ties with society, the unconnected individual. Anomic: the accustomed relationship between the individual and society is suddenly shattered or disrupted. Loss of job, relationship, or fortune. Emile Durkheim 1951. Risk Profile. • Single white male. • Adolescent on risk increases particularly between 25 and 40, • • • • • and then further at 65+. Recent relationship problems. Loss of employment. Legal difficulties. Alcohol and other drugs. Estrangement from children. Psychosocial Risk Profile. • • • • • • • • • • Loss of social supports. History of victimization. History of “quitting” employment. Aggressive-impulsive tendencies; Polarized thinking. Suicide notes. Past history of suicide-lethality. Opportunity. Occupation: health professionals, secondary trauma. Childhood trauma. Family history of suicide. Psychiatric/Medical Risk Profile. • Recent diagnosis: schizophrenia, mood disorder, anxiety • • • disorders, and substance disorders. Insomnia, poor concentration and anhedonia. Chronic and terminal illness, particularly chronic pain. Huntington’s; MS; Head Injury; AIDS; and Epilepsy Mitigating Factors. • • • • • • Internal. Successful past response. Positive coping skills. Beliefs. Reality capacity. Resiliency. • • • • • External. Children/pets. Therapeutic relationship. Sense of responsibility. Social supports. Evaluation. • Plan, Lethality, Opportunity and Intent (PLOI). • Examples of questions to ask to elicit information. • Normalize feelings: discuss the fact that 15 million people experience suicidal ideation every year. • Ask about their thoughts, ask for them to elaborate and discuss have they ever acted on these thoughts? • Have you ever felt so sad that life does not feel worth living? • Have you ever thought about hurting yourself? • Do you have a plan? • Have you practiced or rehearsed this plan? • Do you have a means to complete this plan? • Do you have a location picked out? Or a time that you would attempt this plan? • What has stopped you in the past? Evaluation Cont’d. • Have you attempted suicide before? (Really explore: What kept them alive? Were they surprisingly interrupted by chance? Did they specifically pick out a lethal method, a time and location, and by all means should be dead?). • Anyone in your family completed suicide? Central Themes of Hopelessness: Four very specific questions: (These questions must be weaved into the conversation, as these are a clearer indicator of completers versus gesturers). • Unlovability. Do you feel that you are a lovable person? • Helplessness. Do you believe that you can solve your • • problems? Psychache. Do you believe that your pain will lessen? Perceived Burdensomeness. Do you believe that everyone would be better off if you were not here/dead? The Fueling Emotions. • • • • Hopelessness. Death is better than life. The problem cannot be solved. I will always be in pain. • • • • Helplessness. I am flawed. The world would be better without me. I cannot control my life. J. Klott, 2007 Management. • Treat the person not the condition. • Treat the ambivalence. • Help them cope. • Where do you hurt? And How may I help? • The suicide prevention contract, or “no-harm” contract is commonly used in clinical practice, but should not be considered as a substitute for a careful clinical assessment. The willingness to enter such a contract should not be viewed as an absolute indicator of suitability for discharge. They are contraindicated with clients that are agitated, psychotic, impulsive, or under the influence of an intoxicating substance. Further, they should not be used with newly admitted or unknown clients. Management Cont’d. • Determine a setting for treatment and supervision. • Attend to client safety. • Establish a cooperative and collaborative therapeutic relationship. • Treat in the setting that is the least restrictive setting, yet most likely to be safe and effective. • Use of family (Safety sweep of environment). • Outpatient. • Partial hospitalization. • Crisis Unit. • Inpatient (voluntarily or involuntarily). • Maintain support of family members, who themselves may be vulnerable to their own stress and inability to cope. Documentation. • After risk assessment and treatment options, documentation of findings and course of treatment is ESSENTIAL. This not only provides continuity of care, but safeguards the treator/assessor in terms of liability of risk management. It also allows clear collaboration with colleagues or supervisor. • Documentation must be completed immediately following the risk assessment and treatment option chosen. If in doubt as to how to treat, then seek input immediately from colleagues or supervisor, before allowing the treatment option to be implemented. • It is better to err on the side of caution, knowing that the client will remain safe. Documentation Example. • Client is a 35 year old recently separated white male, who is experiencing severe depression and feelings of hopelessness. He is currently experiencing possible future charges for Domestic Violence, and has disclosed prolonged and chronic use of AOD. He is currently expressing suicidal ideation, and has reported past attempts with high lethality, and a current plan and opportunity. Additional risk is assessed due to his circumstances and lack of supports, and his inability to verbalize meaningful protective factors. The plan is to provide inpatient hospitalization, with full suicide precautions and further observation. He will also receive medication management, and psychotherapy, until further stabilization. Statistics on Completed Suicide. • Inpatient observation is used to protect clients from harming themselves or others, either in the form of constant observation, or 15 minute checks. In spite of these precautions, approximately 1500 patients yearly complete suicide within an inpatient setting, even while these precautions are in place. It is estimated that 13% of inpatients require this type of observation. • 78% of patients who completed suicide within Hospital settings denied suicidal ideation during their last communication with staff, and that 73% of completed suicide in inpatient settings occur after 28 days of admission. • Suicidal ideation at the time of admission increases the risk factors, however, research has found that less than 50% of patients who completed suicide in a Hospital, were admitted with suicidal ideation. • A high proportion of suicide completers have visited their Primary Care Physician within the previous 6 months. References. • American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th Edit. Washington, D.C. • American Psychiatry Association, 2009. Practice Guidelines for the Assessment and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Behaviors. Obtained from the World Wide Web, 01/16/09. http://www.psychiatryonline.com/content.aspx?aID=56046 • Durkheim, E., 1951. Suicide: A Study in Sociology. The Free Press, Simon and Schuster, New York, NY. • Gliatto, M.F., and Rai, A.K. (1999). Evaluation and Treatment of Patients with Suicidal Ideation. American Family Physician.March 1999 • Grant, J., 2007. Suicide assessment and Treatment, in Current Psychiatry, Vol 6:6, June 2007 References Cont’d. • Klott, J., 2007. Stopping the Pain, Suicide and Self-Mutilation. PESI, Eau Claire, WI. • Muzina, D. J., 2007. Suicide Intervention in Current Psychiatry, Vol 6:9 Sept 2007. • Melville, H., 1851 Moby Dick, Harper and Row, New York, NY. • Schneidman, E. 1973. Deaths of Man. Quadrangle, The New York Times Books, New York, NY. • Schneidman, E. 2001. Comprehending Suicide, American Psychological Association. Washington. D.C. • Schneidman, E. 2004. Autopsy of a Suicidal Mind. Oxford University Press. New York, NY.