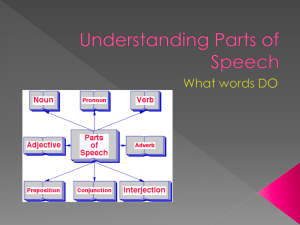

Theme 2 Morphemic and categorial structures of the word

advertisement