Lecture_1 - Department of Biological Science

advertisement

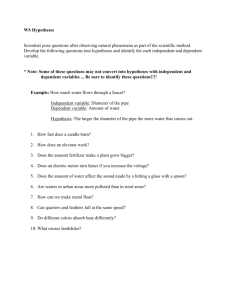

Welcome to Experimental Biology • • • • Get a syllabus First day policy applies today (take roll) You do need to purchase a book from Target TA’s are Sarah Tso, David McNutt, Amanda Buchanan, Elise Gornish, and Ben Nomann I. Purpose of this Course • Teach basic scientific method • Create scientific literacy in our biology majors to make better citizens • Introduce students to research at a Research I university (supposed to be for sophomores, but it is never too late) II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions 1. Science: investigation of rational concepts that can be tested using observation and experimentation -- defined by method of investigation -- limited to the study of physical universe -- must be amenable to experimentation. II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions 1. Science 2. Scientific Method: formal way of asking and answering questions in science -- common to all fields of science II. Scientific Method After anyone touches switch, lights come on Hey, can you turn off the light the same way? Flip the switch! Does the switch on the wall control the lights? Flipping the switch turns on the lights. II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions 1. Science 2. Scientific Method 3. Hypothesis: any proposed explanation for an observed phenomenon, used for further exploration -- not a guess, as it is based on prior knowledge -- generally stated as a testable fact II. Scientific Method So, the scientific method deals with formulating and testing hypotheses. Things to remember: 1. Science is limited to the physical universe – does not include supernatural forces. Anything that can't be tested by observation. and experimentation. is not science, by definition e.g. A ball falling could be explained by either Gravity - vs divine intervention -- Science can only test one of these. e.g. "creation science" = oxymoron 2. Doing science = uncovering rules that govern physical universe (vs. facts) when testing hypotheses. We assume that a given set of physical conditions will produce a consistent result II. Scientific Method Please note that these definitions do NOT suggest that science and religion are at odds. Instead, science is based on a formalized methodology that operates on the physical universe. It simply cannot be applied to many religious, spiritual questions, and therefore in general has nothing to say about the religion. This is related to a current interesting controversy in evolutionary biology and philosophy. A variety of “atheistic humanists”, principally the biologist Richard Dawkins and the philosophy Daniel Dennet argue that belief in Darwin’s view of evolution necessarily leads to a belief that there is no god(s). They suggests that religion is a “cowardly flabbiness of the intellect that afflicts otherwise rational people”. II. Scientific Method Other prominent scientists and philosophers, such as Ken Miller and FSU’s Michael Ruse, argue that this view is not only wrong, but is also “dangerous, both at a moral and a legal level.” Ruse goes on to suggest that Dawkin’s view is essentially promoting atheism as a religion. This has important implications for the legal arguments among creationism, intelligent design, and evolution, because the current courts are tossing out intelligent design in schools because of its religious content, over the supposed pure scientific view of evolution. --- We won’t resolve this general question in this class. I (along with most major religions in the United States) feel that evolution has a firm basis in scientific methodology and should be taught in schools. “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution” (T. Dobzhansky). II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions B. How do we test hypotheses in Science? -- by the rejection of alternative hypotheses -- no such thing as proof, only evidence. -- pose reasonable alternative hypotheses (often includes a null hypothesis proposing no effect). -- design experiment that can discriminate or disprove alternate hypotheses. -- experiments should basically disprove all hypotheses but one. II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions B. How do we test hypotheses in Science? Let’s consider another light example -- a light that does not go on when we flip the switch. We might suspect that either the lamp or the bulb is bad. A good test would be to move that bulb to another lamp in the same room and try it again. If again the light does not go on, have we proven that the bulb, rather than the lamp, is bad? No, there are other possible explanations. For example, the power could be out. We have simple eliminated the hypothesis that only that lamp is bad. Another similar example is the earth and sun -- who goes around whom? II. Scientific Method Perhaps a better example is the earth and sun -- who goes around whom? If we assume that the sun goes around the earth once a day, we can make some predictions about when the sun will rise and set that hold up pretty well. We could also even develop a way to explain seasons, by simply having the sun take an erratic course around the earth. So, does this mean that the sun does go around the earth? II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions B. How do we test hypotheses in Science? -- in short, the problem is that with deductive logic you can get the right answer (a successful prediction) for the wrong reason. Therefore a more conservative method is favored - the rejection of hypotheses that give rise to inaccurate predictions. - Nothing is ever proven, only disproved. - Science must always be open to new ideas, new alternative hypotheses. II. Scientific Method A. Some Definitions B. How do we test hypotheses in Science? C. Why learn the scientific method? -- it is necessary to make responsible decisions about the world around you, especially here in Biological Science at FSU. Examples: -- Buck-tooth faced baby -- Vioxx, Celebrex, Aleve -- politics, advertising, insurance -- Global Warming II. Scientific Method Vioxx. Celebrex. Now Aleve. What's a Patient to Think? By ANAHAD O'CONNOR Published: December 28, 2004, New York Times. When Audrey Eisen flicked her computer on last Monday night and read the news that the painkiller Aleve had been linked to heart attacks, she winced in disbelief. Ms. Eisen, 64, a retired professor who lives in New York, had just returned from her drugstore with a package of Aleve. Her pharmacist allowed her to return it the next morning, no questions asked. It was the third painkiller in four months that Ms. Eisen, who has degenerative spine and disk disease, had quit abruptly because of studies linking the drugs to heart attacks. She flushed her Vioxx down the toilet in September, after it was withdrawn from the market, and switched to Celebrex. But when problems surfaced with Celebrex this month, she had to stop that, too. II. Scientific Method U.S. approves weight-loss drug for obese dogs 07/01/2007 14:07 By Susan Heavey WASHINGTON (Reuters) – U.S. health officials have approved the first prescription weight-loss drug aimed at treating Americans’ increasingly plump pooches. The drug, Pfizer’s Slentrol, helps decrease appetite and fat absorption to help the roughly 5 percent of U.S. dogs that are obese lose weight. Another 20 percent to 30 percent are overweight (two-thirds of Americans are also overweight or obese). Also known as dirlotapide, the once-daily liquid can also cause various side effects, including vomiting, loose stools, diarrhoea and lethargy. Slentrol is not for human use and will carry warnings to discourage people from using it, the FDA said. II. Scientific Method Steven Lima, Thomas Valone, and Thomas Caraco. 1985. Foraging-efficiency -- predation-risk trade-off in the grey squirrel. Animal Behaviour 33:155-165. II. Scientific Method Steven Lima, Thomas Valone, and Thomas Caraco. 1985. Foragingefficiency -- predation-risk trade-off in the grey squirrel. Animal Behaviour 33:155-165. Predict that tendency to carry a food item should decrease with distance of food from cover (predation risk) and increase with item size (food reward). Both risk and reward should influence behavior Experiments were conducted in Highland Park in Rochester, New York. The reward was chocolate-chip cookies, cut to weigh 1, 2, or 3 g. More “natural” foods were buried rather than eaten and cookies may be a “natural” food for a park squirrel anyway. Food was placed at different distances from trees. II. Scientific Method Steven Lima, Thomas Valone, and Thomas Caraco. 1985. II. Scientific Method Steven Lima, Thomas Valone, and Thomas Caraco. 1985. Foragingefficiency -- predation-risk trade-off in the grey squirrel. Animal Behaviour 33:155-165. The authors conclude that the results support their hypothesis. Simple models that only incorporate foraging rate or only exposure to predators are insufficient, as both are important.