Liz Myers 24th Oct 2014 - the Peninsula MRCPsych Course

advertisement

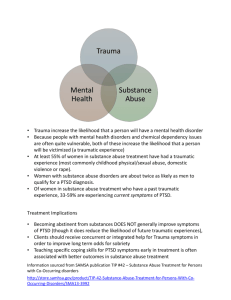

Outline for today........... • Adolescent development, including neuroscience • Introduction to adolescent mental health problems; and some treatments you may come across (e.g. ADHD,ASD,PTSD, depression, anxiety, eating disorders, psychosis, self harm, substance misuse) • Risk and resilience Different aspects of development • Physical – growth and maturation of the brain and body. • Cognitive – skills associated with perception, such as thinking, memory, problem solving, attention, perseverance and language skills. • Emotional – awareness, expression and management of feelings and ability to empathise. • Social – making, maintaining and ending relationships, understanding of social roles, rules, morals, customs and values. Vocation/occupation • Identity – self-evaluations (e.g. self-esteem and self-efficacy), autobiography (i.e. life stories) and sense of belonging. What impacts on early years development? • Parental factors – attachment history and resources, health and wellbeing, abuse, loss and trauma, disabled parent/child, Domestic violence, Substance misuse, Parental MH, neglect and abuse, expectations (gender, reminders of ex- or abusive partners) • Child factors – risk and resilience, prenatal factors (e.g. chromosome abnormalities, intra-uterine growth, pre-natal infection, congenital abnormality), temperament, disabling conditions (hearing loss, physical and learning disabilities, developmental disorders), premature • Environmental factors – social network, connectedness, resources and poverty, gains and losses, transitions, severe illness, lack of opportunity to practice skills, poverty • Cultural factors – awareness and definitions of development and abuse • THESE FACTORS ALL INTERACT….. What interferes with ‘healthy’ brain development? • • • • • • • Prenatal exposure to drugs and alcohol Malnutrition Neglect – lack of stimulation Poor attachments Physical and sexual abuse Parental ill-health Chronic stress Stages of Adolescence So what happens in Adolescence? • Critical period of brain development • 2nd wave of overproduction of gray (thinking) matter • Frontal cortex myelination (insulation) • “Pruning” (cut back weak branches) • Continuing process until early 20s at least • SO – A WORK IN PROGRESS The Whole Brain is Affected The Pre-frontal cortex and the amygdala PFC – involved in executive function: Increase in pfc neurons just before puberty Pruning. Thickening & myelination The amygdala is involved in the unconscious processing and memory of reactions to emotional events. Increases in size Emotional Functioning in Adolescence • There is a mismatch between emotional and cognitive regulatory modes in adolescence • Brain structures mediating emotional experiences change rapidly at the onset of puberty • Maturation of the frontal brain structures underpinning cognitive control lag behind by several years • Adolescents are left with powerful emotional responses to social stimuli that they cannot easily regulate, contextualise, create plans about or inhibit The PFC Executive function The Amygdala Processes and interprets sensory data Assigns emotional meaning, especially negative Modulates the flow of information from the cortex to the hypothalamus Affects autonomic, endocrine and affective responses Reading Emotion from Facial Expressions 1. This face is expressing... Embarrassment Fear Sadness Surprise http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/ei_quiz This face is expressing... Sadness Pain Anger Disgust http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/ei_quiz http://greatergood.berkeley.edu/ei_quiz This face is expressing... Sadness Shame Disgust Contempt MAIN ISSUES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Substance Use School/occupation Identity Family/whanau support Multiple needs – comorbidities Social disadvantage & exclusion Appropriate & accessible services Implications • Brain more sensitive to experiential input during adolescence (executive function) • ?These skills may be more difficult to “hardwire” after puberty • ?So should we be looking at specific interventions at this age USE IT OR LOSE IT?? Social Cognition • Perspective taking – “step into other’s shoes” • Experiment – shown a face & word, need to name the emotion (uses working memory & decision making) – pubertal “dip” • “Face processing” – (happy,sad,angry,fearful,disgusted,surprised) Young teens use “gut reactions” These abilities develop during puberty (fear,disgust,anger) and then can use reasoning EXECUTIVE FUNCTION • The capacity that allows us to control & coordinate our thoughts & behaviour • Different skills involved e.g.: • ability to initiate and stop actions • control impulses and regulate emotions • monitor and change behaviour as needed DOMAINS OF IMPAIRMENT • • • • • • • Attachment Biology Affect/emotional regulation Dissociation Behavioural control Cognition Self concept Adolescent changes 2 • The adolescent capacity to inhibit responses is not fully mature; mortality rises in adolescence due to risk taking behaviour • Adolescents tend to take greater risks than adults. • Adolescents tend to foresee fewer possible outcomes of their risk-taking, underestimate the likelihood of negative outcomes, and overvalue the benefits of having fun and obtaining the approval of others • BUT is some risk taking essential for healthy development? So what happens in Adolescence? • Adolescence, (esp 14 to 16), constitutes another “critical” period” of particularly dramatic developmental changes • Neural pathways are “hardwired’ by the process of pruning and myelinisation • Parietal and temporal lobes mostly mature in adolescent brain – vision, hearing, spatial awareness, language And also……. • Frontal & prefrontal cortex continue to develop until early 20s – cognitive processing and executive function • Development is idiosyncratic and non-linear • The brain regions undergoing transformation during adolescence are highly sensitive to stressors, including environmental influences Adolescent changes 1 • Continued improvement on: • Selective attention, working memory, problem solving • Perspective taking – “step into other’s shoes” • Social cognition - Young teens use “gut reactions”, abilities develop during puberty and then can use reasoning Why would anyone DO that? The Pros and Cons Increased risk of damage from drugs/alcohol Increased risk of developing addiction Increased risk of mental illness Increased risk-taking Areas of the brain controlling impulsive behaviour, judgement and emotional control mature last. Greater capacity to learn and create. Greater capacity to embrace high risk/high reward decisions. Sleep Family Influences • Increase in parent-child conflict, mostly mothers –autonomy, authority • Conflict may be valuable as part of development – may encourage advanced reasoning • Midlife crisis for parents??? • Sibling relationships – high degree of conflict common! • Children don't present themselves to services • Still low cultural competency of professionals? • Cultural difference in expression and tolerance of symptoms More specifically….. • • • • • • • • Prosocial father’s absence Antisocial father’s presence Coercive parenting Mothers with depression (whilst rearing children) Concentration of crime in families Marital conflict and domestic violence Low supervision, weak parent child attachment Genetic liability and effect of children's behaviour on parents Effects of Trauma • Chronic stress can lead to changes in brain structure and function because it occurs at a sensitive developmental period • This can present as: fluctuations in mood, suicidal thoughts, and intense distress which may lead to self harm. • Acting out, risk taking behaviour, self destructiveness, and delinquency • Depression, withdrawal Some clinical implications • Neurochemical changes, leading to increased physiological responsivity • Dysregulation of biological stress system • Decreased cognitive function, attention, concentration, executive function, memory & learning • Can interfere with the capacity to integrate sensory, cognitive & emotional information. Difficult to organise & express feelings, struggles to allow others to help • Hyper arousal, fighting, avoidant, dissociative. …. Some Important Considerations • EF -The capacity that allows us to control & coordinate our thoughts & behaviour • Different skills involved e.g. working memory, voluntary response inhibition, decision making, filtering out unimportant information, holding in mind a plan to carry out in the future, inhibiting impulses, Problem solving!! • Social Cognition - Perspective taking – “step into other’s shoes”, “Face processing” – (happy,sad,angry,fearful,disgusted,surprised) • Young teens use “gut reactions” - these abilities develop during puberty (fear,disgust,anger) and then can use reasoning Ripples in a Pond - Why Violence and Abuse Happens Interpersonal and Family Factors Abusive parenting Abusive expression of power differentials Poor conflict resolution & communication skills Lack of interpersonal respect Types of Violence Child Abuse Sexual Violence Dating Violence Domestic Abuse Bullying Youth Violence Hate Crimes Elder Abuse Individual Factors Genetics Hormones Nutrition Males Alcohol Drugs Tobacco Emotional intelligence Past abuse Genetics Hormones Nutrition Females Physiological Learning Disability Individual Factors alterations in Increased Brain risk of brain following perpetrating abuse affect abuse the limbic ADHD Conduct system, Disorder midbrain Anti-Social & frontal lobes Behaviour & Offending Personality PTSD behaviour Disorders Risk behaviour Brain Dissociative Disorders Increased risk of re-abuse Learning Disability Withdrawal Alcohol Drugs Tobacco Past abuse Depression Borderline & Suicide Personality Disorder STIs Pregnancy Obesity CHD Cancer CHD Cancer -Plasticity of the brainAlterations in the brain are adaptable especially until the mid- 20’s CBT/ therapy, protective & pro-social skills reduces harm & aids recovery Community and Societal Factors Legislation re alcohol & drugs Deprivation & economic inequalities Historical & cultural norms Prejudice & inequalities re gender, age, race, sexuality Nurse J 2006 33 Psychiatric Diagnoses……. • EMOTIONAL DISORDERS – adjustment disorders, anxiety disorders, depression • DISRUPTIVE BEHAVIOUR – O.D.D., Conduct disorders • DEVELOPMENTAL – ADHD, Autistic spectrum • INTELLECTUAL DISABILITY • SUBSTANCE USE • PSYCHOSIS (inc Bipolar I Disorder) Psychosocial Immaturity • Susceptibility to peer influence • Attitudes towards & perception of risk • Future orientation • Capacity for self management These factors may affect decision outcomes, even if cognitive processes are mature Also consider “identity crisis”, short lived risky behaviours – mostly stop with settled identity (grow out of it). So why join a gang? • "The gang has taken on the responsibility of doing what the family, school, and other social agencies have failed to do – provide mechanisms for age and sex development, establish norms of behaviour, and define and structure outlets for friendship, human support an the like." (Vigil 1988:168) 21st Century Issues? • The changed nature of the social environment in which young people find themselves compared with that of previous generations. • The nature of peer pressure and role models has been radically altered by exposure to electronically connected social networks and to very different media content. • The human brain continues to mature into the early 20s; the nature of brain maturation and the complicated environment in which young people are currently living place adolescents at higher risk for mental health disorders, particularly anxiety and depression. • The adolescent brain is clearly more sensitive to both alcohol and cannabis, with potential long-lasting adverse consequences Key Messages 1. 2. 3. 4. • Secure & healthy relationships provide building blocks for human health & development These begin in infancy and support healthy brain, social and emotional development. Humans are born with predisposition for relatedness; a sense of belonging and connectedness to others (we are social beings); the opposite –alienation; disconnection; no sense of belonging relate to wide range of problems. Difficulties children experience and present to others are outcomes of difficulties in their relationships; harm; loss and trauma and how these are internalised. Theories include evolutionary biology and attachment –the importance of safety for survival (Crittenden); neuroscience, attachment and brain development; Developmental psychopathology emphasising the importance of early attachment history and trauma & later mental health difficulties . Why Adolescent/Youth Mental Health? • Adolescence and early adulthood is a critical time for personal development. The major threat to this comes from mental ill health with 75% of mental and substance use disorders emerging by age 25. More severe disorders are typically preceded by less severe disorders that are rarely brought to clinical attention. By age 21, just over half of young people will have experienced a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. • Latest research reveals the complex interplay of genes, environment, psychological and social factors underpinning the development of these conditions in young people. These conditions can have a devastating impact on young people’s potential to establish their own independence and goals. • Mental health problems that commence in young adulthood have important long-term vocational consequences, including reduced workforce participation, lower income and lower economic living standards at age 30. “Roughly half of all lifetime mental disorders in most studies start by the mid-teens and three quarters by the mid-20s. Later onsets are mostly secondary conditions. Severe disorders are typically preceded by less severe disorders that are seldom brought to clinical attention” Kessler et al, Current Opinion Psychiatry, 2007 Common Psychological problems of Looked after Children • • • • • • • • • • • Attachment problems Relationship problems Attention and Concentration Difficulties Low tolerance/control/emotional regulation Anger and aggression Conduct difficulties Anxiety Depression Substance misuse Self-harm High rates of risk taking behaviours DOMAINS OF IMPAIRMENT • • • • • • • Attachment Biology Affect/emotional regulation Dissociation Behavioural control Cognition Self concept AFFECT/EMOTION REGULATION • Easily aroused, high intensity emotions • Difficulty describing feelings and internal experience • Chronic and pervasive low mood, or sense of emptiness & dread • Chronic suicidality • Over-inhibition or excessive expressions of anger • Difficulty communicating desires and wishes ATTACHMENT • Uncertainty about reliability & predictability of the world • Problems with boundaries • Distrust, suspiciousness • Social isolation • Difficulty attuning to other people’s emotional states and point of view • Difficulty with perspective taking SELF CONCEPT • • • • • • Lack of continuous sense of self Low self esteem Shame & guilt Poor sense of separateness Body image disturbance Sense of being ineffective in dealing with environment BEHAVIOUR • • • • • • • • • • Poor impulse control Self destructive Aggression Sleep disturbance Eating disorders Substance abuse Oppositionality Excessive compliance Difficulty understanding & complying with rules Re-enactment of past trauma Therapeutic models • • • • • • Developmental Attachment Trauma Loss Systemic Theory Cognitive Behavioural Theory Ethical Issues • Lots, particularly with this client group – Informed Consent – Confidentiality – Testing procedures – Practical considerations – Legal How resilience has been defined? “Resilience is the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress – such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems, or workplace and financial stressors. It means “bouncing back” from difficult experiences… ….The road to resiliency is likely to involve considerable emotional distress.” American Psychological Association Important Adolescent Factors • • • • • • School – Achieving? Attending??!! Leisure/recreation opportunities Family/parental relationships Peer group Drugs & Alcohol Impulsivity, Risk taking What is resilience? • Individual attributes or trait? (i.e. fairly fixed, such as high intellect) • Factors which predict vulnerability/risk or strengths/protection? (i.e. internal or external, such as educational attainment and family stability) • Processes and mechanisms (i.e. ways in which people deal with adversity, such as ability to seek support and availability of support) So what is resilience? • It’s the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or even significant sources of stress, such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems, education/workplace and financial stresses. • Although resilience often refers to the ability to “bounce back” from difficult experiences before this starts to happen people have experienced emotional pain and sadness as a result of a major adversity or trauma in their lives. • The road to resiliency often involves considerable emotional distress – it comes later on rather than immediately. • Resilience is related to the nature of the risk or adversity, our previous experiences, the quality of our relationships and attachments and the environment in which we live. • Resilience is not a trait that people have or don’t have. Factors associated with resilience The importance of relationships • The primary factor is having caring & supportive relationships within & outside the family. Relationships that offer love, trust and security, provide role models & offer encouragement & reassurance. • Resilient people don’t go it alone, when bad things happens they reach out to the people who care about them and they ask for help The importance of our own personal qualities, attributes and skills • The capacity to make realistic plans and take steps to carry them out; • Having a positive view of yourself and confidence in your strengths and abilities; • The ability to recognise your own feelings & read & understand other people’s feelings; • The capacity to manage strong feelings and impulses; • Being prepared to take appropriate risks and a willingness to try things and think failure is part of life – mistakes are learning opportunities NOTE: the road to resilience is different for everyone. What works for one person may not work for another. Useful websites………….. • International Association for Youth Mental Health www.iaymh.org • www.youngminds.org.uk • www.rcpsych.ac.uk • www.camh.org.uk • www.chimat.org.uk • Locally – Cornwall intranet, CPFT • Cornwall Council – Families Information Service • Children's Care Management Centre 01872 221400 Acknowledgements AND Prof Sarah-Jayne Blakemore Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience University College London Much of the material in this talk is taken from the 1st Edition of Nicola Morgan’s very readable book “Blame My Brain”, the 3rd edition of which has just been published, and from the many excellent papers published by Sarah-Jayne Blakemore. Any errors in the information in this talk are entirely my own. May 2nd 2013 Criterion A: DSM-IV The person was exposed to: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence, as follows: (one required) • Direct exposure. • Witnessing, in person. • Indirectly, by learning that a close relative or close friend was exposed to trauma. If the event involved actual or threatened death, it must have been violent or accidental. • Repeated or extreme indirect exposure to aversive details of the event(s), usually in the course of professional duties (e.g., first responders, collecting body parts; professionals repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse). This does not include indirect non-professional exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures. Criterion B: Intrusion Symptoms The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced in the following way(s): (one required) • Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive memories. Note: Children older than six may express this symptom in repetitive play. • Traumatic nightmares. Note: Children may have frightening dreams without content related to the trauma(s). • Dissociative reactions (e.g., flashbacks) which may occur on a continuum from brief episodes to complete loss of consciousness. Note: Children may reenact the event in play. • Intense or prolonged distress after exposure to traumatic reminders. • Marked physiologic reactivity after exposure to traumarelated stimuli. Criterion C: Avoidance Symptoms Persistent effortful avoidance of distressing trauma-related stimuli after the event: (one required) • Trauma-related thoughts or feelings. • Trauma-related external reminders (e.g., people, places, conversations, activities, objects, or situations). Criterion D:Negative alterations in cognitions or moods • Inability to recall key features of the traumatic event (usually dissociative amnesia; not due to head injury, alcohol, or drugs). • Persistent (and often distorted) negative beliefs and expectations about oneself or the world (e.g., "I am bad," "The world is completely dangerous"). • Persistent distorted blame of self or others for causing the traumatic event or for resulting consequences. • Persistent negative trauma-related emotions (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame). • Markedly diminished interest in (pre-traumatic) significant activities. • Feeling alienated from others (e.g., detachment or estrangement). • Constricted affect: persistent inability to experience positive emotions. Criterion E: alterations in arousal and reactivity • • • • • • Irritable or aggressive behavior Self-destructive or reckless behavior Hypervigilance Exaggerated startle response Problems in concentration Sleep disturbance Specify if: With dissociative symptoms • Depersonalization: experience of being an outside observer of or detached from oneself (e.g., feeling as if "this is not happening to me" or one were in a dream). • Derealization: experience of unreality, distance, or distortion (e.g., "things are not real"). Specify if: With delayed expression. • Full diagnosis is not met until at least six months after the trauma(s), although onset of symptoms may occur immediately. Family Systems • Complex factors relating to family systems must be considered in children with PTSD • Parent’s reports of their child’s experience of symptoms following trauma generally minimise the level of distress as described by the child • Secondary stressors are often involved in cases of childhood or adolescent trauma (relocation, changing schools, separation from family members, financial difficulties of the family) Complex PTSD It is worse if: • it happens at an early age – the earlier the age, the worse the trauma • it is caused by a parent or other care giver • the trauma is severe • the trauma goes on for a long time • you are isolated • you are still in touch with the abuser and/or threats to your safety Complex PTSD • Lack of trust in other people – and the world in general – is central to complex PTSD. Treatment often needs to be longer to allow you to develop a secure relationship with a therapist – to experience that it is possible to trust someone in this world without being hurt or abused. The work will often happen in stages: stabilisation, trauma-focussed therapy Psychological theories.......... • When we are frightened, we remember things very clearly. Although it can be distressing to remember these things, it can help us to understand what happened and, in the long run, help us to survive. • The flashbacks can be seen as replays of what happened. They force us to think about what has happened so we might be betterprepared if it were to happen again. • It is tiring and distressing to remember a trauma. Avoidance and numbing keep the number of replays down to a manageable level. • Being 'on guard' means that we can react quickly if another crisis happens. We sometimes see this happening with survivors of an earthquake, when there may be second or third shocks. It can also give us the energy for the work that’s needed after an accident or crisis. Physical theories......... • Adrenaline is a hormone our bodies produce when we are under stress. It 'pumps up' the body to prepare it for action. When the stress disappears, the level of adrenaline should go back to normal. In PTSD, it may be that the vivid memories of the trauma keep the levels of adrenaline high. This will make a person tense, irritable, and unable to relax or sleep well. • The hippocampus is a part of the brain that processes memories. High levels of stress hormones, like adrenaline, can stop it from working properly – like 'blowing a fuse'. This means that flashbacks and nightmares continue because the memories of the trauma can’t be processed. If the stress goes away, and the adrenaline levels get back to normal, the brain is able to repair the damage itself, like other natural healing processes in the body. The disturbing memories can then be processed and the flashbacks and nightmares will slowly disappear. Complex PTSD • This can start weeks or months after the traumatic event, but may take years to be recognised. • Trauma affects a child's development - the earlier the trauma, the more harm it does. Some children cope by being defensive or aggressive. Others cut themselves off from what is going on around them, and grow up with a sense of shame and guilt rather than feeling confident and good about themselves. Complex PTSD • • • • • • • • • • As well as many of the symptoms of PTSD described : feel shame and guilt have a sense of numbness, a lack of feelings in your body can't enjoy anything control your emotions by using street drugs, alcohol, or by harming yourself cut yourself off from what is going on around you (dissociation) have physical symptoms caused by your distress find that you can't put your emotions into words want to kill yourself take risks and do things on the 'spur of the moment'. Family Systems • Threat to caregiver is a strong predictor of the development of PTSD in infants and young children • Parents experiences of trauma may precipitate PTSD in their children • Children’s experiences of trauma may precipitate PTSD in their parents • Parents may inflict trauma onto their children (in cases of physical or sexual abuse) Attachment and trauma • Infant and child attachment to a caregiver provides the infant/child with a context through which to organise emotional, cognitive and behavioural interactions (Finzi et. al., 2001). • Three attachment styles; secure, avoidant/ambivalent, and avoidant. Attachment and trauma • Infant and child attachment to a caregiver provides the infant/child with a context through which to organise emotional, cognitive and behavioural interactions (Finzi et. al., 2001). • Three attachment styles; secure, avoidant/ambivalent, and avoidant. Insecure attachment • Child does not see their caregiver as being responsive in times of need • Caregivers may induce traumatic states in their children (e.g., abuse) • Caregivers tend not to interactively repair their child’s negative affective states • Children of abusive caregivers may react with fight-or-flight responses, develop ‘freezing’ responses, or enter a state of ‘fear without solution’ which can result in early dissociative states • Children of abusive caregivers are still dependent on their caregiver; dissociation may allow maintenance of attachment whilst ‘escaping’ harm Implications for therapeutic alliance • Children who have experienced abuse may apply coping strategies informed by early insecure attachment to future relationships • Children may expect similar maltreatment in future relationships • Clinicians need to be mindful of this phenomena when treating traumatised children Shattered Assumptions Shattered assumptions about safety and control can be considered as part of the ‘meaning making’ process that occurs following significant trauma. Prior to a traumatic event; My parents are in control My parents will keep me safe Bad things happen to other people, not me I am worthy and life has meaning Shattered Assumptions Trauma can alter children’s core beliefs about their sense of self and the world. The basic assumptions listed previously can be shattered and reconstituted in forms such as; I am not in control and neither are my parents I am not safe and my parents are unable to keep me safe Bad things can happen to me If bad things happen to me I must deserve it I am not worthy of safety Building relationships with traumatised children and adolescents • Relationships with therapists may be especially important for traumatised populations • Building relationships with traumatised young people can be challenging for therapists • Therapists should foster predictability, consistency and safety in the relationship and in sessions – Use ritual greetings, session format, taking things out and putting away, goodbye Building relationships with children and people adolescents • traumatised Traumatised children and young may test out the limits of the relationship with their therapist – – – – Rule breaking Dangerous behaviour Physical aggression Inappropriate sexual behaviour Therapists must set limits on behaviour whilst maintaining relationship; the young person needs to know that their behaviour does not change the therapists view of them as a person. Treatment of PTSD in children and adolescents Treatments that have been found to effectively treat PTSD in children and adolescents include; • Trauma-focused Cognitive Behaviour Therapy • Systemic family systems approaches • Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing Posttraumatic Growth and TraumaInformed Resilience. • Positive change arising from a persons’ recovery from trauma, through the effective use of coping skills following exposure to trauma • Trauma-informed resilience is a similar concept whereby a person’s ability to ‘bounce back’ from adversity is strengthened following successful recovery from trauma (Steele & Kuban, 2011). Posttraumatic Growth and TraumaInformed Resilience Trauma informed therapy will foster; • physical and emotional safety of the child • self-regulation • sensory cognitive integration • trauma-informed relationships and environments • trauma integration. References • • • • • • • American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: APA. Brewer, J. & Sparkes, A. (2011). Parentally bereaved children and posttraumatic growth: Insights from an ethnographic study of a UK childhood bereavement service. Mortality, 16, 204-222. Carrion, V. G., Weems, C. F., Ray, R., & Reiss, A. L. (2002). Toward an empirical definition of pediatric PTSD: The phenomenology of PTSD symptoms in youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 166-173. Critendon, P. M. & Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1989). Child maltreatment and attachment theory. In Child Maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect by Cicchetti, D. & Carlson, V. Cambridge University Press: United Kingdom. De Zulueta, F. (2009). Post-traumatic stress disorder and attachment: possible links with borderline personality disorder. Advances In Psychiatric Treatment, 15, 172-180. Dyb, G., Jensen, T. K., & Nygaard, E. (2011). Children’s and Parents’ posttraumatic stress reactions after the 2004 Tsumani. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 16, 621-634. Fernandez, S., Cromer, L., Borntrager, C., Swopes, R., Hanson, R. F., & Davis, J. L. (2013). A case series: Cognitive-behavioural treatment (exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy) of trauma-related nightmares experienced by children. Clinical Case Studies, 12, 39-59. References • Finzi, R., Ram, A., Har-Evan, D., Shnit, D. & Weizman, A. (2001). Attachment styles and aggression in physically abused and neglected children. Journal of Youth and Adolescents, 30, 769-786. • Graham-Bermann, S. A., Castor, L. E., Miller, L. E., & Howell, K. H. (2012). The impact of intimate partner violence and additional traumatic events on trauma symptoms and PTSD in preschool-aged children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25, 393-400. • Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 377-391. • Lemma, A. (2010). The power of relationship: A study of key working as an intervention with traumatised young people. Journal of Social Work Practice, 24, 409-427. • Levendosky, A. A., Huth-Bocks, A. C., Semel, M. A., & Shapiro, D. L. (2002). Trauma symptoms in preschool aged children exposed to domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 17, 150-164. • Ostrowski, S. A. (2010). Development of child posttraumatic stress disorder in pediatric trauma victims: The impact of initial child and caregiver PTSD symptoms on the development of subsequent child PTSD. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 70, 5838. References • Pearce, J. W. & Pezzot-Pearce, T. D. (2007). The Therapeutic Relationship in Psychotherapy of Abused and Neglected Children (2nd Ed.). The Guilford Press: New York. • Roth S. & Friedman M. J. (1998): Childhood Trauma Remembered: A Report on the Current Scientific Knowledge Base and Its Applications, Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 7, 83-109. • Scheeringa, M. S., Myers, L., Putnam, F. W., & Zeanah, C. H. (2012). Diagnosing PTSD in early childhood: An empirical assessment of four approaches. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25, 359-367. • Scheeringa, M. S., Weems, C. F., Cohen, J. A., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Guthrie, D. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52, 853-860. • Stafford, B., Zeanah, C. H., & Scheeringa, M. (2003). Exploring psychopathology in early childhood: PTSD and attachment disorders in DC: 0-3 and DSM-IV. Infant Mental Health Journal, 24, 398-409. Category of Protective factors • 1) Individual personality attributes • 2) Family characteristics • 3) Environmental influences (peers, school and community) Profile of the Resilient Child • • • • 1) 2) 3) 4) Social competence Problem-solving skills Autonomy Sense of purpose and future Social Competence • “Resilient children are considerably more responsive (and elicit more positive responses from others), more active, and more flexible and adaptable.” • Bonnie Benard Comic relief • More likely to have a good sense of humor. • Alternative ways of looking at things. • Ability to laugh at themselves and ridiculous situations. • Humor as transcendent strength. • Cleaning up the mess at Micky D’s. Problem solving skills • Ability to think abstractly and flexibly. • Rutter study of abused and neglected girls in British slums. • Good planning skills led to good marriages. • Didn’t repeat the cycle of abuse. • Street kids have to negotiate the demands of their world to survive. Sense of purpose and future • Healthy expectancies, achievement motivation, persistence, hope. • Strongest predictor of positive outcome. • Education aspirations better predictor than academic achievement. • Children of alcoholics pin success on sense of the future. Peer and friends • Often overlooked role in school and community environments. • Positive peer pressure and support. • Particularly effective in reducing drug and alcohol use. • High risk behavior. Families and communities • Families exist within communities. • Communities have important role to play in supporting families. • Power of school to influence the outcome of children from high-risk environments. • Protective factors within the school. Social Cohesiveness • Competent community depends on the availability of social networks. • Provide links within the community. • Networks on campus, extended family, musical groups, friends. Access to community resources • Resources necessary to healthy human development: • Health care, childcare, housing, education, job training, employment and recreation. • Guard against risk factors of social isolation and poverty. • Build social bonds that link individuals and organizations to resources. Cultural norms • Expectations of community. • Community expectations of youth: resource or source of problems? • Youth must view themselves as stakeholders in the community. • Actively involved in organizations and activities. • Society set guidelines for youth. Messages about young people and resilience Chronic stressors can cause more long term problems than acute events. An accumulation of stressors is more damaging e.g. ‘Children may often be able to overcome and even learn from single or moderate risks, but when risk factors accumulate, children’s capacity to survive rapidly diminishes’ (Newman and Blackburn, 2002). Over-protection from stressors can reduce opportunities to develop the skills to deal with adversity. Messages about intervention 1. Reduce vulnerability and risk 2. Reduce the number of stressors and ‘pile-up’ 3. Increase available resources 4. Mobilise protective processes 5. Foster resilience strings (Masten, 2004) In adolescence In adolescence attachments are still very important Patterns of behaviour will have become more entrenched Young people are likely to have developed their own repertoires of coping ‘Resilience Matrix’ Devised in collaboration with Sally Wassell and Robbie Gilligan Resilience ‘domains’ Designed with children in mind, but adaptable to other ages cottish Government (2008) A Guide to ‘Getting it right for every child’ Model for Intervention Identify and support protective resources Understand the impact of adversity of transition Remove or reduce the impact of adverse effect of transition Nurture capacity to benefit from these resources Example of Social Competencies Intervention • Need to be clear about the aim of the intervention – consider the comment by Masten and Coatsworth that attempts to boost self-esteem to improve behaviour can lead to ‘misbehaving children who think very highly of themselves.’ Need an ethos where the approach to self-esteem takes account of relationships: ‘Appreciating my own worth and importance and having the character to be accountable for myself and to act responsibly toward others’ (California State Department of Education) Example of Positive Values Intervention • Parent/carer factors associated with pro-social behaviour (Schaffer, 1996 and Zahn-Waxler, RadkeYarrow & King 1979): • provide clear rules and principles for behaviour, reward • • • • 108 kindness, show disapproval of unkindness and explain effects of hurting others present moral messages in an emotional, rather than calm manner attribute prosocial qualities to the child by telling him or her frequently that they are kind and helpful model prosocial behaviour themselves provide empathic care-giving to the child. Social Competencies • Development of social competence is associated with parenting/caring that is warm, sensitive and provides clear boundaries and requirements for behaviour. • Antisocial behaviour is associated with an environment that is harsh, punitive, rejecting and inconsistent. • Need to pay attention to: • cognitive areas • affective areas • behavioural areas. Self-efficacy and competence Resilience associated with sense of self-efficacy, mastery, planful competence and appropriate autonomy. Self-efficacy: Problem-focused coping – change the problem if you can or • Emotion-focused coping – change how you think and feel about the problem ‘A body of research points to ‘problem-focused’ coping, rather than avoidant or passive responses, as being most successful for a range of adversities. This involves responding to hardship by taking active steps to modify features in the environment or oneself that are contributing to the difficulty in question’ (Hill et al, 2007) • ‘Planful competence’ (Rutter) – being able to see different options. In addition: • Empathy, positive values, making a contribution - all contribute to resilience. Active coping • ‘Many children report using avoidance or distraction as a coping strategy when there are problems at home’ (Gorin, 2004). • ‘Periodically separating themselves mentally and physically from the home’ (Bancroft et al 2004). • ‘Some ways of ‘escaping’ are beneficial, but others are costly in terms of an unplanned and problematic transition to adulthood and an unsettled or unstable early adult life.’ (Velleman and Templeton, 2003). Work with the grain… ‘The child is a person and not an object of concern’ (Butler-Sloss, 1988). Therefore we need to concentrate on building on, and enhancing, existing coping mechanisms; involving young people as active participants and avoiding potentially unhelpful consequences. Practitioners link it with principles for practice respectful engagement with, and involvement of the service user in practice 2. the use of solution-focused and strengths-based approaches to practice 3. the need to target all ecological levels 4. the need to take a holistic and multi-agency approach. 1. Solution focused It may be that these terms are being used as ‘shorthand’ for more positive approaches to practice that counteract the preoccupation with risk and problems that can characterise bureaucratic systems Further research needed to examine whether the adoption of optimistic discourses can lead to better outcomes for children over and above the specific model for intervention that is used. Ecological UK services focused heavily on the coping and skills of the individual child with associated support for the parents or carers, and the Australian services were dedicated to improving the well-being of parents and family unit and placing that unit within the best possible community network. The research showing factors at different ecological levels to be associated with resilience suggests should target all levels (Werner & Smith, 1992). Multi-agency The concept of resilience is one that has resonance for all disciplines The promotion of the resilience of children, families and communities can offer a shared approach for the professional network Focusing on what can be done can galvanise the protective network. STRATEGIES anger control / emotional intelligence INTENDED OUTCOMES raised self-esteem / better peer relationships / improved school experience Daniel, B., & Wassell, S. (2002). Assessing and Promoting Resilience in Vulnerable Children I - III. London: Jessica Kingsley. Gilligan, R. (1998). The importance of schools and teachers in child welfare. Child and Family Social Work, 3(1), 13-26. Gilligan, R. (1999). Enhancing the resilience of children and young people in public care by mentoring their talents and interests. Child and Family Social Work, 4(3), 187-196. Gilligan, R. (2001). Promoting Resilience: A Resource Guide on Working with Children in the Care System. London: BAAF. Hill, M., Triseliotis, J., Borland, M., & Lambert, L. (1996). Outcomes of social work intervention with young people. In M. Hill & J. Aldgate (Eds.), Child Welfare Services: Developments in Law, Policy, Practice and Research. London: Jessica Kingsley. Luthar, S. S., & Zelazo, L. B. (2003). Resilience and Vulnerability: Adaptation in the Context of Childhood Adversities. In S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and Vulnerability. New York: Cambridge University Place. Masten, A. S., Best, K. M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 425-444. Newman, T. (2004). What Works in Building Resilience. London: Barnardo's. 120 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) ADHD is a pervasive, heterogeneous behavioural syndrome characterised by the core symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. Autistic Spectrum Disorder • An intrinsic condition, ASD manifests core features which are pervasive and include deficits in: - Social communication - Social interaction - Social imagination • Current prevalence of all ASD diagnoses: 1.6% • Children with an ASD have a higher risk than peers of developing other mental health problems. • NICE have recently released a draft proposal for clinical guidelines which will cover recognition, referral and diagnosis of ASD in children. Conduct disorder and ODD • Conduct disorder: repetitive and persistent pattern of antisocial, aggressive or defiant conduct and violation of social norms • Oppositional defiant disorder: persistently hostile or defiant behaviour without aggressive or antisocial behaviour Associated conditions • Conduct disorders are often seen in association with: – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) – depression – learning disabilities (particularly dyslexia) – substance misuse – less frequently, psychosis and autism Recommendations for children > 12 years • There is limited evidence only for effective interventions with older children/young people. • Those programmes which show early promise are currently being evaluated, for example: - Multi-systemic therapy - Functional family therapy • These approaches tend to be intensive and expensive. They are not currently available locally, though specialist CAMHS do offer other forms of therapeutic support to some families (family therapy, for example). Depression • At any one time, the estimated number of children and young people suffering from depression: – 1 in 100 children – 1 in 33 young people • Prevalence figures exceed treatment numbers: – about 25% of children and young people with depression detected and treated • Suicide is the: – 3rd leading cause of death in 15–24-year-olds – 6th leading cause of death in 5–14-year-olds • Transition to Adult services, where appropriate, requires careful planning Depression KEY SYMPTOMS ASSOCIATED SYMPTOMS persistent poor sadness, or low or irritable mood: AND/OR loss of interests and/or pleasure fatigue or low energy or increased sleep poor concentration or indecisiveness low self-confidence poor or increased appetite suicidal thoughts or acts agitation or slowing of movements guilt or self-blame Mild Up to 4 symptoms Moderate 5-6 symptoms Severe 7-10 symptoms Depression When to refer to the specialist CAMH service: • Depression with multiple-risk histories in another family member • Mild depression and no response to interventions in tier 1 after 2–3 months (Low level intervention and “watchful waiting”) • Moderate or severe depression (including psychotic depression) • Recurrence after recovery from previous moderate or severe depression • Unexplained self-neglect of at least 1 month’s duration that could be harmful to physical health • Active suicidal ideas or plans • Young person or parent/carer requests referral Anxiety • No specific NICE guidance for children and young people for Anxiety, though guidance is available for children with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Obsessional Compulsive Disorder • Type of anxiety experienced by the child (social, generalised, panic, separation, specific phobia) and degree of impairment to functioning is important to detail in referral • Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) and other behavioural approaches indicated for most anxiety disorders. Obsessional-Compulsive disorder (OCD) • Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): characterised by the presence of either obsessions (repetitive, distressing, unwanted thoughts) or compulsions (repetitive, distressing, unproductive behaviours) – commonly both. Symptoms cause significant functional impairment/distress • 1% of young people are affected – adults often report experiencing first symptoms in childhood • Onset can be at any age. Mean age is late adolescence for men, early twenties for women Anorexia nervosa • Severe dietary restriction despite very low weight (BMI <17.5 kg/m2) • Morbid fear of fatness • Distorted body image (that is, an unreasonable belief that one is overweight) • Amenorrhoea • A proportion of patients binge and purge • In assessing whether a person has anorexia nervosa, attention should be paid not just to one off weight and BMI but also to the overall clinical assessment (repeated over time), including rate of weight loss, growth rates in children, objective physical signs and appropriate laboratory tests. Include all information in referral. Bulimia nervosa • Characterised by an irresistible urge to overeat, followed by selfinduced vomiting or purging and accompanied by a morbid fear of becoming fat. • Patients with bulimia nervosa who are vomiting frequently or taking large quantities of laxatives (especially if they are also underweight) should have their fluid and electrolyte balance assessed. o Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and specifically fluoxetine, are the drugs of first choice for the treatment of bulimia nervosa.The effective dose of fluoxetine is higher than for depression (60 mg daily). • No drugs, other than antidepressants, are recommended for the treatment of bulimia nervosa. “Isn’t it just bad parenting?” • Anorexia nervosa – Any family • Schizophrenia – Any family – Genetic factors – Environment factors • Autism – Any family – Genetic factors • ADHD – Any family – Genetic factors Examples of causes • • • • • • • Genes Bereavements Change of school Bullying Trauma Loss Social and family stress • • • • • • • Isolation Alcohol and drugs School exams Physical illness Being a child carer Environment No known cause