Evolutionary Psychology, Lecture 5: Female Mate Preferences.

advertisement

Evolutionary Psychology

Workshop 5: Partner-Wanted Ad’s.

Learning Outcomes.

1. Review the evidence concerning the use of lonely-heart

personal advertisements (LHPA’s) to understand human

mate preferences.

2. Carry out a content analysis of lonely-heart

advertisements.

3. Discuss the findings in light of theoretical predictions.

Background.

Lonely-hearts personal advertisements (LHPA's) are a

highly popular means of meeting potential short- or longterm mating partners.

Around 80% of major newspapers and magazines surveyed

ran LHPA's (Thiessen et al., 1993).

There are problems in that submitters of LHPA's may

represent a biased sample, or that the information provided

may be inaccurate (Wiederman, 1993).

However, according to Thiessen et al., (1993) and

Greenless & Mcgrew (1994) LHPA's provide an ecologically

valid dating and mating arena in which to analyse human

reproductive strategies and mate preferences.

Advantages of Content Analysis

of LHPA’s.

1. Use of LHPA's is common, and those who place a LHPA

do so for valid interpersonal reasons and not just because

they want to be volunteers in research.

2. The placing of a LHPA is a 'real-life' act with genuine

consequences and so is akin to a naturalistic observation

rather than a controlled laboratory study.

3. LHPA users offer a broader range of age, class, and

experiences than do most studies on mate preferences,

which rely on undergraduate students.

4. The commodities of exchange are clear - both sexes

provide

information

about

themselves

and

their

preferences.

5. The success or failure of a strategy can be followed-up.

6. The technique is simple to conduct and evaluate.

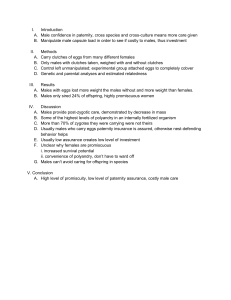

General Predictions.

Based on sexual selection / parental investment we could

argue that females may seek males who demonstrate their

ability and willingness to contribute to a relationship or on

their genetic quality.

Males place a higher emphasis on female fertility and could

thus be predicted to seek information concerning youth,

attractiveness, parental skills, and fertility.

Female Predictions.

We might expect females to offer:

Youth and attractiveness ('cute', 'buxom' 'petite',

'shapely'), caring behaviour ('kind', 'gentle', 'sincere'),

perhaps the promise of sex ('cuddly', 'sensual' 'into fun

times').

They may seek:

Resources, and the willingness to invest them (i.e.

'homeowner',

'employed',

'professional'

'generous',

'sharing' etc).

Intelligence ('educated'), mate reliability ('honesty'), and a

partner who is older than themselves ('mature').

Certain physical features (i.e. 'tall', 'muscular') but may not

particularly emphasise 'good looks'.

Male Predictions.

We might expect males to principally offer:

Resources (i.e. status, job description, property ownership,

likes holidays abroad) and reliability ('honest', 'mature'

etc).

While they may not offer good looks they may emphasise

their height or physique ('tall', 'rugged', 'healthy').

They will seek:

Younger attractive partners and will probably not demand

intelligence, social status, or resources.

Certain characteristics such as 'generosity', 'good sense of

humour', 'kindness', 'caring nature' etc may be sought by

both sexes.

Previous Content-Analysis Studies.

In an analysis of more than 1000 LHPA's, Wiederman

(1993) reported than female advertisers sought resources

11 times more often than males.

Males were likely to offer resources and the willingness to

invest them (e.g. ‘homeowner’, ‘employed’ ‘educated’,

‘generous nature’) than women.

Males who mentioned resources were significantly more

likely to receive a reply.

Thiessen et al., (1993) also reported that males were

significantly more likely to offer resources, while women

were more likely to seek them.

Greenless & Mcgrew (1993) reported that males sought

youth, attractiveness, and sexual availability, while women

sought evidence of resources, financial security, and

possible long-term commitment.

Resource Offering and Requests.

From Thiessen et al., 1993, p216.

The Factor of Age.

In a review of age preferences, Kenrick & Keefe (1992)

found that females typically preferred males who were

around 5-10 years older than themselves, and this

remained fairly consistent over the life span.

Greenless & McGrew (1994) reported that the average age

of male advertisers was 36 as opposed to 34.9 for women

and women are significantly more likely to stipulate the age

of their preferred partner (older than themselves).

In around 900 LHPA's from the 'Observer' newspaper

Pawlowski & Dunbar (1999) found that women typically

prefer males 2-3 years older than themselves and this

remains stable across the age range, males however

request increasingly younger partners as they age.

Age Preferences.

Data from Kenrick & Keefe, 1993, p80.

Age Preferences continued.

Data from Pawlowski & Dunbar, 1999, in Barrett et al., (2002) p100.

Characteristics of the Sender.

Waynforth & Dunbar (1995) showed that individual

preferences are contingent upon what the person has to

offer. In more than 800 LHPA's they found:

Women become less demanding as they get older (as their

reproductive value declines).

Males become more demanding as they get older

(resources increase).

Women offering attractiveness are more demanding.

Males offering resources are more demanding.

Males with fewer resources offer family commitment.

Males and females with dependant offspring make lower

demands.

Individuals from higher socio-economic groups make

higher demands than those from lower groups.

Successful LHPA's.

Lynn & Shurgot (1984) found that females describing

themselves as 'slim' received more replies.

Tall, males with dark hair received more replies than

shorter males with lighter hair.

Green et al., (1984) compared the most ‘popular’ male and

female 'dates' with the most 'unpopular’ from a video

dating agency.

Younger and more attractive females were most popular as

were older males with high status.

Rajecki et al., (1991) reported that in general women

received more replies than men, with younger women and

older males receiving the most replies.

Pawlowski & Koziel (2002)

Using matrimonial bureau records of 551 male and 617

female LHPA's they analysed which particular stated traits

influenced the 'hit rate'.

As in previous studies males offered resources and sought

attractiveness, while females offered attractiveness and

sought resources/commitment.

For males the most important predictors of hit rate (in

order of success) were education, age (older), height (tall)

and marital status (single) and resources.

For females the most important factors influencing hit rate

were as follows: weight (thin), height (medium), and

education (less).

Surprisingly attractiveness offered was not a significant

predictor.

Activities.

1. Use the table provided to put together a tally sheet of

features offered and requested by each sex.

We will collect the data together and discuss the findings.

2. Using your knowledge concerning successful LHPA's,

write an LHPA for a male and female that you think should

bring them success.

Results.

% of 460 LHPA's offering/seeking

attractiveness

60

50

%

40

female

male

30

20

10

0

offer

request

Type

Results.

% of 460 LHPA's offering /seeking

youth

40

35

30

%

25

female

20

male

15

10

5

0

offer

request

Type

Results.

%

% of 460 LHPA's offering/seeking

resources

50

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

female

male

offer

request

Type

Results.

% of 460 LHPA's offering/seeking

physical attractiveness

60

50

%

40

female

30

male

20

10

0

offer

request

Type

References.

Green, S.K., Buchanan, D.R., & Heuer, S.K. (1984). Winners,

losers, and choosers: a field investigation of dating initiation.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10: 502-511.

Greenless, I.A., & McGrew, W.C. (1994). Sex and age differences

in preference and tactics of mate attraction: analysis of published

advertisements. Ethology and Sociobiology, 15: 59-72.

Kenrick, D.T., & Keefe, R.C. (1992). Age preferences in mates

reflect sex differences in human reproductive strategies.

Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 15: 75-133.

Lynn, M., & Shurgot, B.A. (1984). Responses to lonely hearts

advertisements: effect of reported physical attractiveness,

physique and coloration. Personality and Social psychology

Bulletin, 10: 349-357.

Pawlowski, B., & Dunbar, R.I.M. (1999). Impact of market value

on human mate choice decisions. Proceedings of the Royal Society

of London, B, 266: 281-285.

References continued.

Pawlowski, B., & Koziel, S. (2002). The impact of traits offered in

personal advertisements on response rates. Evolution and Human

Behaviour, 23: 139-149.

Rajecki, D.W., Bledsoe, S.B., & Rasmussen, J.L. (1991). Successful

personal ads: gender differences and similarities in offers,

stipulations, and outcomes. Basic and Applied Social Psychology,

12: 457-469.

Thiessen, D., Young, R.K., & Burroughs, R. (1993). Lonely hearts

advertisements reflect sexually dimorphic mating strategies.

Ethology and Sociobiology, 14: 209-229.

Waynforth, D., & Dunbar, R.I.M. (1995). Conditional mate choice

strategies in humans: evidence from 'lonely hearts'

advertisements. Behaviour, 132: 755-779.

Wiederman, M.W. (1993). Evolved gender differences in mate

preferences: evidence from personal advertisements. Ethology

and Sociobiology, 14: 331-352.