Digestive and Circulatory Systems

advertisement

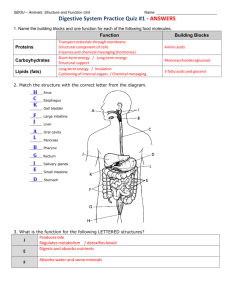

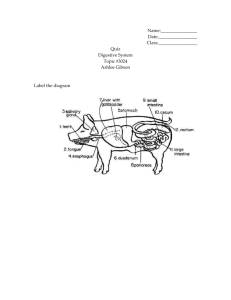

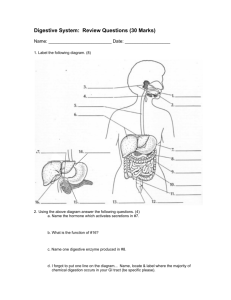

Sarah Lopes A&P II – Dr. Jayne Jarger The Digestive and Circulatory Systems While all bodily systems are vital to our survival, the digestive and circulatory systems are among the most prominent. Several times a day, we put the digestive system into action by consuming food for energy, and we can physically feel our heart beating at all times. These two systems are closely intertwined, and one could not operate without the other. The digestive system begins with the mouth, where food is mechanically broken down with the teeth and salivary amylase begins to chemically break down carbohydrates. The muscular tongue maneuvers the food around the mouth during chewing and then aids in deglutition of the bolus of food. The bolus travels down the esophagus as muscles contract behind it to push it along. This process is known as peristalsis, and it occurs throughout the alimentary canal. When the bolus of food reaches the stomach, it must pass through the lower esophageal sphincter, which is also known as the cardiac sphincter, because the receiving end of the stomach is referred to as the cardia. The stomach has other named portions, such as the fundus, which is the most superior point, the greater and lesser curvatures on the lateral and medial aspects, and the pyloric region on the exiting end of the stomach. The mucosa of the stomach is covered in folds called rugae and also contains gastric pits, which become gastric glands as they move deeper into the epithelium. This is where gastric juice is produced to chemically digest the ingested food. The stomach is where protein digestion is initiated. The mixture of gastric juices and ingested food is called chyme, and it is released in small amounts through the pyloric sphincter into the small intestine. The small intestine is where lipid digestion is initiated, and where the majority of digestion occurs. There are 3 sections: the duodenum on the proximal end, joined to the pylorus of the stomach, the jejunum, and the ileum on the distal end, joined to the large intestine. The liver and pancreas are considered to be digestive accessory organs, and are connected to the duodenum via ducts which release bile and pancreatic juice, respectively. Bile is composed of several compounds, including bile salts, which emulsify fats. Pancreatic juice contains a variety of enzymes that break down the food components of the chyme, as well as bicarbonate ions that neutralize the hydrochloric acid released by the stomach. The lining of the small intestine has ridges known as circular folds, which are covered in finger-like villi. The cells of the villi have their own projections called microvilli, which make up the brush border. There structures serve to provide maximum surface area for absorption of nutrients. As the chyme passes through the small intestine, nutrients are absorbed through the mucosa and enter the bloodstream, with exception of the lipids, which enter the lacteals of the lymphatic system and later enter the blood through lymphatic ducts. Indigestible matter eventually reaches the cecum of the large intestine after useful nutrients have been extracted, and this leftover material is formed into feces. Under normal circumstances, water is reabsorbed at the large intestine (colon). After passing through the ascending, transverse, and descending colon, waste matter arrives in the rectum and exits through the anus. The cardiovascular system includes the heart, arteries which carry blood away from the heart, and veins which carry blood back to the heart. In systemic circulation, arteries carry oxygen-rich blood to tissues, and veins carry oxygen-poor blood away from the tissues. On the contrary, pulmonary arteries leading to the lungs carry oxygen-poor blood, and once oxygenated, pulmonary veins carry the blood back to the heart so that it can be distributed around the body. The heart has 4 chambers: the right and left atria and right and left ventricles. Deoxygenated blood enters the right atrium from the superior and interior venae cavae, passes through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle, and then out toward the lungs through the pulmonary trunk. Returning from the lungs, oxygenated blood flows into the left atrium, through the biscuspid (mitral) valve into the left ventricle, and out through the aorta to all tissues of the body. The familiar heartbeat sound is created by the closing of the atrioventricular valves just before systole, followed by the closing of the semilunar valves just before diastole. The beating of the heart is controlled by the cardiac conduction system, made up of cells that have the unique ability to contract without nervous or hormonal input. The arterial and venous systems are actually one continuous loop that carries blood to tissues and back again. Similar to the alimentary canal, they are surrounded by layers of muscle that constrict to propel their contents along. As these vessels move more distally from the heart, they become more and more narrow until they reach such a small diameter, only one RBC can pass through at a time. The RBCs carry oxygen via hemoglobin molecules, which contain iron absorbed through the digestive system. As previously mentioned, all other nutrients enter the bloodstream as well, and are carried to appropriate bodily tissues. At the same time, mesenteric arteries carry oxygenated blood to the digestive organ tissues and mesenteric veins carry deoxygenated blood away. Also, bile salts from the liver are recycled via the portal vein, carried back from the duodenum to the liver several times during the digestion of each meal. Lastly, water absorbed through the digestive system is needed for normal blood plasma volume.