Clinical Skills - University of Sydney

advertisement

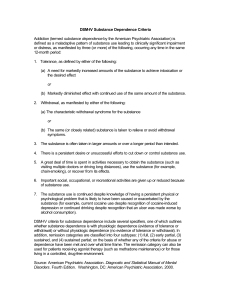

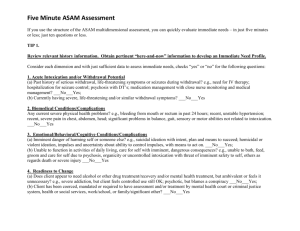

Clinical Skills © 2009 University of Sydney Module Learning Outcomes To be better able to : • Engage in a therapeutic relationship • Make a drug and alcohol assessment by: – history-taking and – physical examination • Provide appropriate advice and brief intervention for substance use issues Case study • Jason, a 36 year old man, presents to your surgery requesting a medical certificate to cover today only. • He went out with friends last night, drank about 15 standard drinks and overslept in the morning. He felt too hung-over to work. How would you approach this situation? What advice should you offer Jason? Does Jason have evidence of a disease? Aims of consultation Engagement Assessment Goal Setting Engagement: the first step What is engagement? • Building a working relationship – – – – showing that you care building rapport building trust working towards mutually acceptable goals – analysing any ‘counter-transference’ that may occur and detaching from any instinctive feelings, if necessary Engagement How to engage people: • • • • • • • Explain (and provide) confidentiality Interview individually Appropriate setting Flexible approach Be non-confrontational Be non-judgmental Be yourself Limits of confidentiality In NSW, we must notify DOCS of: • Injecting drug users <16 yrs old – NSPs may not obtain sufficient information • Children at risk due to carer’s substance abuse • Homeless age 16+, now need to obtain consent • Pregnant IDU placing future infant at risk • Must notify police if knowledge of a serious criminal offence involving a sentence of 5 years or more. In NSW, not required to notify: • IDUs age >16 to DOCS • 14-16 yr olds generally do not require parental consent for medical or counselling intervention if they understand the issues • Condoms and injecting equipment may be given to anyone who requests them Practical suggestions • Consult DOCS, senior colleague or Administration for difficult cases • Keep careful notes concerning decisions about notification Overview of assessment • What is the current status? – Reason for presentation (including social factors) – Is there intoxication or withdrawal? • What is the drug use consumption? – Currently and in the past – Patterns and routes of administration • What are the physical and psychosocial consequences or coexisting problems? • Is there a substance use diagnosis? – Harmful use or dependence • What is the current motivation for change? History taking • Tailored to circumstances – Comprehensive assessment is not always necessary or helpful on first contact – If necessary, can be done over several sessions – What do I need to know in this case at this time? • Assessment is itself a therapeutic process – Links substance use to problems, sometimes for the first time – Quantifies use, enhances self awareness For every patient you see… • Quantified alcohol history • Quantified smoking history • High index of suspicion for other substances – More detailed questions where indicated • Where positive history exists – Assess whether daily intake is increasing or decreasing and if so, why? – Assess avenues for intervention to decrease intake For a comprehensive drug and alcohol history Ask about all the drugs of abuse: • Tobacco • Alcohol • Misuse of prescribed drugs • Illicit drugs: – Cannabis – Stimulants (MDMA, amphetamine, methamphetamine, cocaine) – Opioids – Hallucinogens What is a standard drink? NB: home poured drinks are variable but are approx. 2 standard drinks Drink-less Program, 2005 Non-standard drinks Drink-less Program, 2005 Low risk drinking levels NHMRC Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (2009): 1. For reduced lifetime risk of harm from drinking: 2 standard drinks or less in any 1 day (for healthy men and women, aged 18 and over) 2. For reduced risk of injury in a drinking occasion: No more than 4 standard drinks per occasion. 3. For people <18 years of age: safest not to drink Under 15: Especially important not to drink Between 15-17: Delay drinking initiation for as long as possible 4. Pregnant (or planning a pregnancy) or Breastfeeding: Not drinking is safest option Reaching a diagnosis Harmful use – associated with clear physical or psychological harm Dependence Three or more of the following within the last year – strong desire to use – loss of control – withdrawal – tolerance – salience – use despite harm International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) Physical examination 1: • Look for signs of intoxication or withdrawal: – Drowsiness (alcohol, benzodiazepines, opiates) – Agitation (sedative withdrawal, or stimulant toxicity) – Tremor (alcohol, benzodiazepines withdrawal) – Diaphoresis (alcohol and opioid withdrawal) – Slurred speech, ataxia (alcohol, benzodiazepine intoxication) – Pupils (especially opiates) – Confusion (e.g. Wernicke’s, DTs) or stimulant/hallucinogen intoxication/psychosis Physical examination 2: Medical complications • Mental State: sensorium, intoxication, mood, signs of psychosis • Vital signs (e.g. fever, tachycardia of alcohol withdrawal or infectious complications) • Venepuncture sites / track marks (recent or old) • Lymphadenopathy • Liver • Heart • Lungs Old track marks Where is your patient ‘at’? What is his/her current motivation? • What is the presenting problem? – e.g. sore foot, accommodation? • Does your patient want to stop or cut down? Assessment ‘Readiness to Change’ Model Pre-contemplation Relapse Contemplation Maintenance Action Determination Prochaska & Di Clemente, 1982, Psychotherapy --- Practice, 19 Principles of management • • • • • Use of evidence-based interventions Establishing a therapeutic relationship Motivating the patient towards a goal Holistic approach Withdrawal management (detoxification) if needed • Relapse prevention • Harm minimisation Intervention approaches • Counselling – individual – group – brief and long-term • Pharmacotherapy • Peer support e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous Early and brief intervention • An intervention as short as five minutes can produce a sustained reduction in consumption • Early intervention leads to reduced consumption and related problems • Targets those at risk of harm, but typically not dependent Early and brief intervention • Proactive, opportunistic detection • Consists of brief advice or counselling at the point of detection • For users not ready to change, may increase their motivation • For users wanting to change: – advising on appropriate goals and strategies – support Early and brief intervention Why intervene early? • There are more hazardous and harmful substance users than dependent users • Substance users don’t tend to seek help unless they have advanced problems • Harder to treat once dependence is established • Early intervention is simple, acceptable and cost-effective Early and brief intervention Components of brief intervention Use ‘FLAGS’: – Feedback – Listen – Advice – Goals – Strategies Bien et al, 1993, Addiction, 88 Early and brief intervention A good outcome from brief intervention: • Reduction or cessation of use (even temporary) • Starting to think about reducing • Agreeing to accept referral Motivational enhancement therapy • Aims to increase motivation to change behaviour • Emphasizes the patient’s right to choose • Assumes the responsibility and capability for change are found within the patient Motivational enhancement therapy 5 Key Components: • Express empathy • • • • Elicit ambivalence Elicit self-motivational statements Display counselling micro-skills Roll with resistance Motivational enhancement therapy Strategies • Explore ambivalence – ‘What’s good about your drug use?’ – minimise, but validate – ‘What’s not so good?’ - expand – Explore discrepancies – Resolve these through change • Display counselling micro-skills – e.g. active listening, supportive counselling that is non-judgmental • Enhance self-efficacy (the patient’s belief in their ability to achieve these goals of substance use change) • Help decision making, through problem solving • Summarise; make suggestions Goal-setting Goals must be: • Realistic and achievable • Specific and observable • Client’s goals rather than those of others Goal-setting Whose goals? • Patient vs family vs therapist • short-term vs long-term • drug-specific vs other health and lifestyle issues • Look at the social context – Spouse told patient to come in, court-mandate, etc Harm minimisation as an interim measure • Long term abstinence may not be achievable on the first episode of treatment • Prevention of complications may lead to better health when the decision to stop drug use is finally taken What if s/he doesn’t want to change? • This is part of the change model (precontemplation) • Leave the door open for future contact • Agree to disagree – Need to accept patient autonomy • Consider any harm reduction strategies – Address presenting issue – Safe injecting or alternative routes e.g. nasally, orally (long evolutionary history of protection against pathogens) – Welfare needs Why harm reduction? • Even if we are willing to “write off” such people, society pays the price via crime, viral infections, health care costs, legal costs • Difficulty of eliminating supply • Free choice: we can advise on good habits but not enforce them • Drug users who want to stop may not be able to do so (dependence) Harm reduction Some examples • Avoidance of driving when intoxicated • Safety when intoxicated • Child protection • Thiamine in alcohol dependence • Safe injecting • What you buy is not always what you think • Avoid over-heating, dehydration with stimulants Drug-seeking behaviour • The attempt to obtain prescriptions for psychoactive drugs by making false or deliberately exaggerated claims of pain or distress • A common and significant problem • Inability to identify and manage drugseeking patients can make a doctor’s practice unpleasant and frustrating • An opportunity for intervention Presentations of Drug Seeking • • • • • Pain Insomnia Emotional distress Drug withdrawal Repeatedly running out of medication early • Lost scripts or medication Clinical Features • Ask for their drug of choice by name • Unlikely story e.g. forgot to bring medication on vacation • Refuse all other therapeutic options • Make it difficult to confirm their story e.g. present after hours &/or weekend • Going to multiple doctors • May present with signs of intoxication Drugs sought • Commonly – benzodiazepines, opioids • Less commonly – other sedatives, stimulants, anticholinergics Assessment When Drug Seeking is Suspected • Take an alcohol and drug history • Patients with a current or past history of dependence on other drugs are at greater risk for opioid &/or benzodiazepine dependence. • Examine for signs of intoxication or withdrawal • Examine for track marks in antecubital fossae, lower legs, neck Confirmation Possibilities • Previous doctors, hospital(s) • Medicare Australia Prescription Shopping Information Service - 1 800 631 181 – Doctor needs to apply for an “access number” – With patient consent detailed reports available • NSW Pharmaceutical Services Branch 02 9879 5239 • Other people if appropriate Diagnosis • Is the person dependent? • Is the person drug seeking? • Is the person currently on an opioid treatment program? • What is plan of management? • Do you refuse to prescribe or not and under what conditions? Management • Discuss openly with the patient if you believe they are drug dependent and why you think they’ve come • Offer help and treatment for their problems as indicated Saying ‘no’ • Empathise but be firm • Make it clear early on that there are limits on what you are prepared to do • Say ‘no’ early on to an inappropriate request e.g. “I don’t prescribe benzos to patients I don’t know” • Give reasons for your decisions and plan of management, offer pt some alternative (eg refer to ED). If you are going to prescribe … • Small amounts and safe supply • Form contract including what happens if management is not adhered to • Ensure Medication is part of an appropriate and comprehensive management plan. • Regular follow up • For OTP patients, refer back to their prescriber / treatment centre Managing difficult behaviour • Set clear limits. Can refer to practice / hospital policies • You have the right to say ‘no’ e.g. scripts for benzos, inappropriate medical certificates • Have good security available for staff, other patients, money, prescription pads • Stay calm and don’t respond emotionally • Judicious use of ‘carrot and stick’ approach • If risk of violence, give way to the patient and call security or police when you can. Maintaining a positive attitude • Treatment is a process, not an event, meaning that it may take some time for a patient to cope in a certain situation. • The course of substance use is often similar to that of a chronic relapsing disease • Those who abuse substances have a right to professional assistance and a fair hearing. Project CREATE Kahan et al, 2001, Subst Abus, 22 Self-test case John is a 34 year old man who presents to the emergency department with painful lump in his right cubital fossa. On physical examination you find an abscess on the right cubital fossa, and track marks on the left. He admits to heroin use. • How would you respond to this patient? • Do you have a role in addressing his drug use? • How would you assess and manage him? Self-test answers • Response to patient – Non-judgmental assessment • Medical role involves: – Assessment, treatment of abscess or other complications, referral , consideration of pharmacotherapy • Assess as per earlier slides • Management – Antibiotics, drainage, pharmacotherapy, counselling Revisiting initial case study • Jason, a 36 year old man, presents to your surgery requesting a medical certificate to cover today only. • He went out with friends last night, drank about 15 standard drinks and overslept in the morning. He felt too hung-over to work. How would you approach this situation? What advice should you offer Jason? Does Jason have evidence of a disease? Revisiting initial case study • Approach by assessment • Response depends on assessment findings. Brief intervention? Can we prevent this from recurring? • Hangover or persisting intoxication? Medical disorders? A work certificate may be appropriate. Contributors • Associate Professor Kate Conigrave Staff Specialist, Drug Health Services, RPAH Associate Professor, Medicine and School of Public Health, University of Sydney • Dr Ken Curry Medical Director, Drug Health Services, Canterbury Hospital Clinical Senior Lecturer, University of Sydney • Professor Paul Haber Staff Specialist, Head of Department, Drug Health Services, RPAH Conjoint Professor in Medicine, University of Sydney All images used with permission, where applicable