Research proposal-2

advertisement

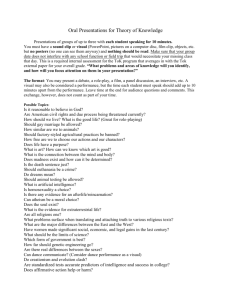

Research proposal Title: How does working in an intermedial setting explore the creative potential of a dance artist? Abstract: This proposal lays out aims and objectives, literature review, methodologies, anticipated problems and research timetable on the topic of intermediality. The literature review reflects on how companies have used intermediality in their work and how new ways of exploring is being represented. The research critically analyses the broad nature of intermediality and leaves an open representation on using and creating with media in live performances. The methodology outlines the paradigmatic framework that will be used in the creative process and what research methods will be undertaken. The proposal concludes with limitations and problems that may arise and a structure to how the creative and research process will materialise. Aims: To create a piece that incorporates film and live performance. To use my own screen dance film as a tool in the choreographic process. Objectives: To work with the company to create movement from the film. To draw upon choreographic processes that I find useful to create material. To create a piece that captures my artist idea of joining film and live performance. Literature review: Intermediality is a mix of digital technology and theatre practice that can use film, television or digital media in a contemporary theatre. (Chapple & Kattenbelt, 2006) Chapple and Kattenbelt explains in their book, Intermediality in Theatre and Performance, that the integration of digital technology and other media in a performance space can create new modes of representation, structuring and positioning of bodies. (2006) This book contains a number of essays written by research groups and draws upon the history of intermediality and how the boundaries between media and theatre can be explored. An essay by Peter M Boenisch titled ‘Choreographing Intermediality in Contemporary Dance Performance’ argues whether ‘intermedialty in contemporary dance performances is located at the point when the bodies of the dancers intersect with their role as a medium, as opposed to the dancing bodies inter-acting with technical media machinery.’ (Boenisch, 2006, p. 151) He explains that media in dance is not a recent discovery but dates back to Merce Cunningham pioneering intermediality into American dance. (Boenisch, 2006) Boenisch describes the use of spatial intermedialtiy in Merce Cunningham’s work; even though there may not be any projected film or light installations, the spatial arrangement of the dancer and the stage makes it look like a film or tv screen. ‘Although the audience still sits in a traditional arrangement opposite the stage, it is the stage space that has changed.’ (Boenisch, 2006, p. 158) In a traditional ballet piece, there is focus on the main dancer who is usually centre stage but Cunningham has created his pieces so that there are many dancers and movement going on at the same time so that audience has a choice on where to focus. Another chapter in this book explains how a company has explored intermediality by incorporating the audience into the performance. The piece consisted of videos, images and text relating to ‘Medea’, the only live performer in the space, and relating to world news. Virtual characters were also projected onto the screens alongside avatar bodies of the audience. The company wanted to create a ‘hypertextual 3D environment’. (Shani, 2006, p. 210) The live dancer in the space was able to control what was projected onto the screen from a computerised wheelchair, where she could re-design and re-work the visuals. The International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media includes many articles that explain how companies and artists have combined media and performance that could inform a choreographers practice and artistic idea. In an article by Helen Bailey, she has focused on a company, Ersatz Dance that work closely with contemporary dance and multimedia and explores pre-recorded and live-recorded video within live performance. Examples of this can be found in Appendix 1 and 2. Through the exploration and focus of intermediality it has led the company to engage with the combination of visual technologies in live performances. (Bailey, 2007) In 1998 Ersatz Dance created a piece, Hyperbolic, that was performance under CCTV cameras then taken into a live performance where they integrated the footage by projection. (Bailey, 2007) The company later shifted their use of media in performances from video to digital animation then to engaging with virtual and live self. The company explored the use of Access Grid as a telematic context which allows a number of technologies to be shared between groups of people in different locations, in other words it is an ‘advanced videoconferencing’. (Wikipedia) Another company that works with this intermediality in this way is a university based project between Liverpool John Moores and Temple university in Philadelphia who videoconference to create and perform collaboratively. ‘These works have explored the medium of telematics performances involving live dance performances in networked dance studio… with live video streamed from a web-cam using the screen projection to connect us in a unique space beyond our institutions.’ (Brooks, 2010, p. 50) Pauline Brooks has worked with visual images combined with dance and then has later moved onto working with telematics choreography and performance. Working with this type of intemediality, limitations occur for example audio delay and picture quality. This can be improved by enhanced or more up to date equipment that will improve the clarity and exploration of the work. In an article by Mark Crossley, he discusses the relationship between live and digital media and how in recent years more companies are integrating media into their work. Crossley discusses pieces by Robert LePage who is one of the world’s leading practitioners of intermedial work and has described the use of using film in a theatre performance as laying out a story to the audience and creating a communication system. ‘If I play in front of an audience in a traditional theatre, the people who are in the room have seen a lot of films, they’ve seen a lot of television, they’ve seen rock videos and they are on the net. They are used to having people telling stories to them in all sorts of ways.’ (Dundjerovic, 2009, p. 51) ‘Seven Streams’ by Robert LePage created a version of this production that used recorded material and live feed that were projected onto a screen. The performers interacted with the digital media, as they were present in the space whilst their live image is projected behind them. Technology is fast evolving and ever changing that audiences can now be involved into intermedial performances rather than sitting and watching the media and live performance happen in front of them. The exploration in intermedial work today is very vast and there could be no limitations to what can be achieved in the future. An approach to intermediality can be taken in either a broad or narrow sense but it is up to the creative company to determine how intermedialty is used. In each of the sources looked at in this review, many different approaches have been used for intermediality and there are many more articles in The International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media that explain how other companies have explored the definition of intermediality. Isabelle Gatt has documented a young company that used a multimedia piece that explored and experimented with stylistic modes. (Gatt, 2012) There are other articles that talk about how improvising with technology can explore the relationships between visual and sonic components. (Millward, 2011) These readings would be beneficial to this study as they could help with the understanding of the creative process that occurs when working with intermediality. Methodology: ‘Research as a process means to search and re-search.’ (Hanstein, 1999, p. 25) Research is an on-going process that can be explorative, improvisational, interpretative and experimental. The research method depends on the type of study. Open interviews and journals would not provide quantitative data such as statistics. Qualitative data allows the researcher to interpret what they've seen and heard and develop an understanding. Modes of enquiry are shaped by a particular research paradigm. This determines the method of approach to the study or question. (Hanstein, 1999) There are three categories of research that make up a paradigmatic framework. A paradigm is a collection of beliefs and establishes how someone sees himself or herself to be in a research study. Hasemen (2006) states that quantitative research embraces a set of scientific and deductive approaches. A positivist researcher works with quantitative data and scientific methods that conclude in structured results such as numbers that can be valid and reliable but may have limitations. A qualitative researcher works with data that is more open and has fewer boundaries, although it may not be valid and reliable as quantitative data is, but it can enable the researcher to explore the meaning and intention behind the findings. Multi-methods used for this can be interviews that allow the interviewer to ask for elaborations on answers, focus groups and case studies. ‘Positivist research attempts to prove or disprove a hypothesis, while postpositivist research attempts to interpret or understand a particular research context.’ (Green & Stinson, 1999, p. 94) Qualitative research methods focuses on the perspectives of the participants and the researcher that is one of the differences to quantitative research that only use the participants’ data. Haseman (2009) states that performative research practice expresses nonnumeric data in the form of moving images, music and sound, live and digital media (Multi-method led by practice). This post-positivist paradigm uses qualitative and quantitative research methods and practice-led research. A post-positivist researchers tend to use broader investigations in their methodologies such as asking why, how and finding out the meanings behind the participants answers. Taking part in open interviews or focus groups allows this action to happen and the researcher is left with a much more personal collection of data to analyse. ‘The principal distinction between this third category and the qualitative and quantitative categories is found in the way it chooses to express its findings.’ (Haseman, 2006, p. 5) A choreographer would fall into the performative paradigm as practice is being undertaken through rehearsals and reflective practice. Hanstein (1999) comments on how in actual practice, research is often shaped by overlapping or integrating modes of inquiry. As a choreographer in past studies the only research methods taken were open interviews via computer documents and film documentation at the end of each rehearsal. A film log enabled the choreographer to analyse the material and note down changes that can then be brought alight in the rehearsal process. For further studies the choreographer has learnt that two research methods alone was not sufficient to carry out a reflective evaluation. The methods mention by Hasemen below need to used to help aid a research investigation. ‘Practice-led researchers have used interviews, reflective dislogue techniques, journals, observation methods, practice trails, personal experience, and expert and peer review methods to complement and enrich their work-based practice’ (Haseman, 2006, p. 8) As a choreographer multi-method research has to be used during a creative process to discover whether the rehearsals are successful for the dancers and choreographer. To find this out the choreographer can carry out fortnightly reflective discussions with their company where in depth thoughts will discover if there are any problems, how they feel about how the rehearsal process is going and whether they feel comfortable performing in the piece. Discussions can also take place in the rehearsal time for instant feedback and for example, relating to this study, the relationship between the live body and projected image needs to be constantly reviewed and reflected on. This is a clear example of practice-led research. ‘Performative research represents a move which holds that practice is the principal research activity- rather than only the practice of performance- and sees the material outcomes of practice as all-important representations of research finding in their own right.’ (Haseman, 2006, p. 7) Reflective practice means learning through experiences and gaining knowledge about the practice. A choreographer needs to critically evaluate their practice so they can analyse what has happened in order to gain new understandings and improve the practice. (Finlay, 2008) As a choreographer, reflection-in-action will play an important role in the choreographic process as problems may occur and actions need to be taken to solve these. While reflecting, new discoveries will emerge whether that’s found from the choreographer, dancers or an outside peer. When a choreographer tries to solve a problem that arises during practice, they firstly need to understand why it has occurred in order to change and solve it. ‘The practitioner’s effort to solve the reframed problem yields new discoveries which call for new reflection-in-action. The process spirals through stages of appreciation, action and appreciation.’ (Schon, 1991, p. 132) This study will involve discovering ideas in every rehearsal so reflection on these finding will be very important to determine a successful outcome. Schon (1991) states that a successful solution of a problem leads to maintaining a reflective journey. So a continual reflective practice will help the choreographer when problems or new experiences arise. Working from a visual stimulus allows the choreographer and the company to experiment, be creative and improvise with the stimuli. Improvising in rehearsals will be a constant form of research, as the choreographer will be discovering new moments within the dance. ‘Exploring, trial and error, improvisation and such acts as defining, refining, elaborating, selecting, rejecting, shaping and reshaping- all experiences that are familiar to us as dance makers- are the fundamental processes of the researcher.’ (Hanstein, 1999, p. 24) A visual stimulus can give a clear intention for the piece from the beginning and can support the material. ‘Visual stimuli provide freedom for the dance composer in that, often, the dance stands alone and unaccompanied by the stimuli. However, the dance should make the origin clear if it is to be an interpretation of it.’ (Smith-Autard, 2010, p. 30) It can provide a strong focus for a performative researcher during the rehearsal process and for the final outcome. The final product of the study will result in an intermedial piece that includes film projected on the screen and in the space alongside live dancers. Through conducting the literature of the proposal an understanding of how other companies have experimented with intermediality in dance and the skills learnt from this can now inform the creative practice in the study. After this study is completed an evaluation will be submitted in the form of a critical evaluative reflection that will discuss research methods and identify issues during the rehearsal process. Word count: 2397 Anticipated problems and limitations I will have to prepare the basic film footage and digital media before rehearsals start so my company and I can work from this in the creative process. Working with film can be unpredictable, as technology cannot always work. There can have problems projecting the image or timing of film could work one week but not the next. Having access to equipment may be a problem if tutors are not available to assist. Creating a coherence between the media and live dancers must always reflected on by myself and tutors as I would like the audience to understand the connection between the two so if the media is not working properly this may cause problems. My dancers availability may become a problem due to other commitments and time of rehearsal. Access to the theatre could be limited due to other students using the space that could cause a problem if I would like to experiment with the projector and use of media. Research timetable Research Timetable Wk commencing 4th Nov Seminar with Fran about research ideas and composing of question. Gather sources for literature review and methodologies Wk commencing 11th Nov Start research proposal. Start to collect possible shots for film. Wk commencing 18th Nov Continue to work on research proposal Wk commencing 25th Nov Hand in draft research proposal Seminar/lecture/tutorial time Wk commencing 2nd Dec Seminar/lecture/tutorial time Arrange rehearsal time slots with company Wk commencing 9th Dec Feedback on draft proposal Wk commencing 16th Dec Hand in research proposal (16th dec) Over Christmas put together a film to start to create from in January. Wk commencing 6th Jan 2014 Show dancers film and discuss working with media. Start to create material from film Wk commencing 13th Jan Set tasks and workshops for dancers to discover raw material Wk commencing 3rd Feb Tutorial 2 with Bernard (show material) Wk commencing 10th & 17th Feb Project week Wk commencing 24th Feb Work and devise from Bernard’s comments. Discuss music option with dancers. Wk commencing 3rd Mar Finalise composition of film and media, continue to experiment with material Wk commencing 10th Mar Set choreographic tasks to experiment with existing material Wk commencing 17th Mar Prepare piece for tutorial. Choose music and discuss costumes. Wk commencing 24th Mar Tutorial 3 with Bernard Wk commencing 31st Mar Work on any notes from Bernard. Put piece together for final outcome Wk commencing 7th Apr Improve any areas and continue to work on material Wk commencing 20th Jan Revisit material and experiment with film Wk commencing 27th Jan Set phrases in preparation for tutorial Wk commencing 28th Apr Revisit piece after 2 weeks off and rehearse final piece in preparation for show. Finalise music and costumes with dancers Wk commencing 5th May Tech and Dress rehearsal and Level 6 platform (7th8th May) Appendices 1. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBSc7xn8hIc- 7/11 2. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mY0czgfE0Vs- 7/11 References Articles Bailey, H. (2007). Ersatz dancing: Negotiating the live and mediated in digital performance practice. International Journal of Performance Arts & Digital Media , 151164. Brooks, P. (2010). Creating new spaces: Dancing in a telematic world. Internationl Journal of Performance Arts & Digital Media , 49-60. Crossley, M. (2012). From LeCompte to Lepage: Student performer engagement with intermedial practice. International Journal for Peformance Arts & Digital Media , 171188. Gatt, I. (2012). Devising multimedia theatre with young performers: Documenting the Marinando Festival's XANDRU U X-XIXA (X&X). International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media , 205-220. Haseman, B. (2006). A Manifesto for Performative Research. Media International Australia incorporating Culture and Policy, theme issue "Practice-led Research" , 98-106. Millward, F. (2011). Visiosonics- Developing moving images in direct response to sound-improvising with technology. Inernational Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media , 171188. Online Article Finlay, L. (2008). Reflecting on ‘Reflective practice’. Retrieved Dec 8, 2013, from The Open University: http://www.open.ac.uk/cetlworkspace/cetlcontent/documents/4bf2b48887459.pdf Rajewsky, I. O. (2005). Intermediality, Intertextuality, and Remediation: A Literary Perspective on Intermediality. Retrieved December 5, 2013, from http://cri.histart.umontreal.ca/cri/fr/intermedialites/p6/pdfs/p6_rajewsky_text.pdf Books Boenisch, P. M. (2006). Mediation Unfinished: Choreographing Intermediality in Contemporary Dance Performance. In F. Chapple, & C. Kattenbelt, Intermediality in Theatre and Performance (pp. 151-166). New York: Rodopi. Chapple, F., & Kattenbelt, C. (2006). Intermediality in Theatre and Performance. New York: Rodopi. Dundjerovic, A. (2009). Robert LePage. Oxon: Routledge. Fraleigh, S. H., & Hanstein, P. (1999). Researching Dance. Evolving modes of inquiry. London: Dance Books. Green, J., & Stinson, S. (1999). Postpositivist research in dance. In S. H. Fraleigh, & P. Hanstein, Researching Dance. Evolving modes of inquiry (pp. 94-123). London: Dance Books Ltd. Hanstein, P. (1999). From idea to research proposal. In P. Hantein, & S. H. Fraleigh, Researching Dance. Evolving modes of inquiry (pp. 22-61). Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh Press. Schon, D. A. (1991). The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. Shani, H. (2006). Modularity as a guiding principle of theatrical intermediality. In F. Chapple, & C. Kattenbelt, Intermediality in Theare and Performance (pp. 207-221). New York: Rodopi . Smith-Autard, J. M. (2010). Dance Composition. London: Methuen Dance. Stinson, S. (2006). Research as Choreography. Research in Dance Education , 201-209. Website Wikipedia. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2013, from Access Grid: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Access_Grid Bibliography Articles Drobnick, J. (2006). Deborah Hay. A Performance Primer. Performance Research. A Journal of Performing Arts , 43-57. Fernandes, C., & Jurgens, S. (2013). Video annotation in the TKB project: Linguistics meets choreography meets technology. International Journal of Performance Arts & Digital Media , 115-134. Hansen, L. A. (2013). Making do and making new: Performativ moves into interaction design. International Journal of Performance Arts & Digital Media , 135-151. Jernigan, D., Fernandez, S., Pensyl, R., & Shangping, L. (2009). Digitally augmented reality characters in live theatre performances. International Journal of Performance Arts & Digital Media , 35-48. Magruder, M. T. (2011). Transitional space(s): Creations, collaboration and improvisation within shared virtual/physical environment. International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media , 189-204. McMeel, D., Brown, C., & Longley, A. (2011). Design, digital gestures and the in(ter)ference of meaning: Reframing technology's role within design and placce through performative gesture. International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media , 5-22.