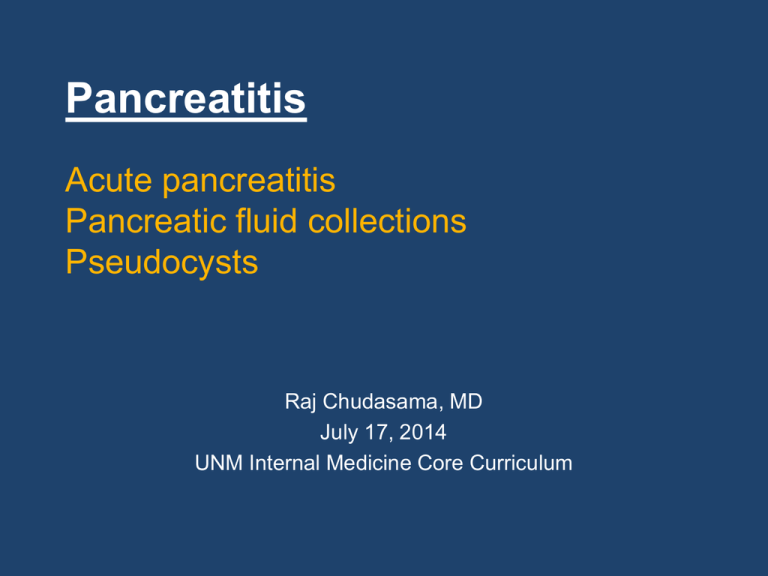

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis

Pancreatic fluid collections

Pseudocysts

Raj Chudasama, MD

July 17, 2014

UNM Internal Medicine Core Curriculum

Outline

• Acute pancreatitis

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Definition

Diagnosis

Determining etiology

Predicting severity

Time course

Necrotizing pancreatitis

Fluid collections

Management pearls

• Pseudocysts

Acute pancreatitis resources

• American College of Gastroenterology Guideline:

Management of Acute Pancreatitis.

– Tenner, Am J Gastro 2013

• Classification of acute pancreatitis—2012: revision

of the Atlanta classification and definitions by

international consensus.

– Banks, Gut 2013

• IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the

management of acute pancreatitis.

– Pancreatology 2013

Acute Pancreatitis - Definition

• Defined by at least the first two of three

features:

– Abdominal pain suggestive of pancreatitis

– Serum amylase and/or lipase levels > 3x

greater than upper limit of normal

– Characteristic findings on CT, MRI, or US.

The Revised Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis

2012

Acute Pancreatitis - Diagnosis

• Serum Amylase

– 40% pancreas

– Sensitivity: 45-85%

– Specificity: 91-99%

• Serum Lipase

– ~100% pancreas

– Sensitivity: 55-100%

– Specificity: 96%

AGA Institute Technical Review on Acute Pancreatitis.

Gastroenterology 2007; 132:2022-2044

Inciting Event

• Gallstones

(45%)

• Alcohol (35%)

• Other (10%)

• Idiopathic

(10%)

Pandol et al. Gastroenterology 2007;132:11271151

Acute Pancreatitis - Imaging

• Transabdominal ultrasonography

– Primary role to identify gallstones or ductal dilation

– Sensitivity to detect stones is ~ 70%

• Contrast enhanced CT scan or MRI

– Reserved for patients

• with unclear diagnosis

• Confirmation of severe acute pancreatitis

• Who fail to improve clinically with initial management

– Optimal timing is 72-96h after presentation

– 15-30% of patients with mild pancreatitis will have

normal CT scan

Determining the etiology

• Transabdominal US should be performed

on all patients

• Check TG (>1000 is significant) if no

gallstones or alcohol use.

• In patient > 40 yr, always consider tumor

• Refer idiopathic pancreatitis to specialist

• Consider genetic testing on pt < 30 yr if

family history of pancreatitis and no other

cause found after 2nd attack

Predicting severe AP

• Severity scoring systems

– Cumbersome

– Require 48h to become accurate

– Severe disease usually obvious regardless

of score

• CT/MRI not reliable in first 24-48h

• CRP takes 72h to become accurate

Predicting severe AP

• Instead, consider

–

–

–

–

–

Early fluid losses

Hypovolemic shock

Organ dysfunction

Patient-specific risk-factors

SIRS

• Heart Rate >90 beats/min

• Temperature >38°C or <36°C

• Respiratory status

– RR >20 breaths/min or

– PaCO2 < 32mmHg

• WBC Count

– >12,000 cells/ul or

– <4,000 cells/ul or

– >10% band forms

Clinical findings associated with

severe pancreatitis

• Patient characteristics

– Age >55

– Obesity (BMI >30 kg/m2)

– Comorbid disease

• SIRS

• Laboratory findings of hypovolemia

– BUN >20 mg/dl, rising BUN

– Hct >44%, rising Hct

– Elevated Cr

• Radiology findings

– Pleural effusions

– Pulmonary infiltrates

– Multiple or extensive extrapancreatic collections

Classification of severity of

pancreatitis

• Mild acute pancreatitis

• Moderately severe acute pancreatitis

• Severe acute pancreatitis

Severity of pancreatitis

• Mild acute pancreatitis

– No organ failure

– No local complications

– By 48h most patients have substantially

improved and begun eating

– Usually require only brief hospitalization

Severity of pancreatitis

• Moderately severe acute pancreatitis

– Local complications

– Only transient organ failure

• Severe acute pancreatitis

– Revision of criteria in 2013

– Persistent organ failure >48h

• By Modified Marshal Score or

• 1993 Atlanta criteria

–

–

–

–

GI bleeding (>500cc/24h)

Shock – SBP < 90 mm Hg

Pa0 2 <60%

Creatinine >2 mg/dl

Organ Failure

• Score of 2 or more for one of the organ

systems using the modified Marshall

scoring system.

The Revised Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis 2012

Acute Pancreatitis – Natural History

• Early phase

– Occurs within the 7 days of onset of disease

– Changes in the pancreas progress from early

inflammation with peripancreatic edema and

ischemia to resolution or permanent necrosis.

– Severity is based on clinical parameters

• Determined primarily by presence or absence of

organ failure

• More than half of the cases of organ failure occur

in the 1st week of admission

Banks et al. Gut 2013

Acute Pancreatitis – Natural History

• Late phase

– Defined morphologically on the basis of CT

findings

– Begins after the 1st week, and can extend for

weeks to months

– Characterized by persistence of systemic

signs of inflammation or

– Presence of local complications like

increasing necrosis, infection and persistent

multi-organ failure

Banks et al. Gut 2013

Timeline

0h

Clinical picture

SIRS

Labs

Risk factors

24h

Clinical picture

BUN

Hct

SIRS

Organ failure

48h

Clinical picture

APACHE II

Ranson criteria

BISAP

72h

Clinical picture

CT imaging

Early Acute Pancreatitis

Interstitial

Edematous

Pancreatitis

Necrotizing

Pancreatitis

Parenchymal

necrosis

Sterile

Infected

Peripancreatic

necrosis

Sterile

Infected

Parenchymal and

peripancreatic

necrosis

Sterile Infected

• Interstitial pancreatitis

– Pancreatic edema in the absence of necrosis

• Necrotizing pancreatitis

– Diffuse or focal areas of non-viable pancreatic

parenchyma >3cm in size or >30% of

pancreas

– Sterile necrosis at equal risk for organ failure

as infected necrosis

Interstitial edematous pancreatitis

• Localized or diffuse

enlargement of the pancreas

• Homogenous enhancement of

the pancreatic parenchyma

• Peripancreatic and

retroperitoneal tissue usually

normal

• Peripancreatic fat stranding

(arrows)

Copyright © BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & British Society of Gastroenterology. All rights reserved.

Banks P A et al. Gut 2013;62:102-111

Necrotizing Pancreatitis (NP)

• Lack of enhancement of pancreatic

parenchyma after IV contrast

• Occurs in ~20% of patients with AP

• Mortality is ~ 15% in patients with NP, and

up to 30% in those with infected necrosis

• Infected necrosis is the most severe

infectious complication in NP

• Intervention may be required for patients

with infected necrosis

Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Parenchymal necrosis

– Seen in fewer than 5%

of cases

– In the 1st week, CT

shows necrosis as a

more homogenous

nonenhancing area,

and later, a more

heterogeneous area

The Revised Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis

Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Peripancreatic necrosis

• Seen in ~ 20% of cases

• Heterogeneous areas of

nonenhancement are

visualized with

nonliquefied components

• Commonly located in the

retroperitoneum and

lesser sac

• Better prognosis than

parenchymal necrosis

The Revised Atlanta Classification of Acute Pancreatitis

Necrotizing Pancreatitis

Parenchymal necrosis with

peripancreatic necrosis

• Seen in ~ 75-80% of

cases most common

• Peripancreatic necrosis

associated with full

necrosis of the pancreatic

parenchyma may be

connected to the main

pancreatic duct.

Infected necrosis

• Acute necrotic collection (white arrows

pointing at the borders of the ANC)

• Gas bubbles (white arrowheads), a

pathognomonic sign of infected necrosis

Copyright © BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & British Society of Gastroenterology. All rights reserved.

• Incidence in patients with

NP is ~ 30%

• Peak incidence at 2 – 4 w

• Mortality ~ 12-40%

• Consider it when there is

persistent sepsis, new-onset

sepsis or clinical

deterioration

• Pathognomonic sign is

impacted peripancreatic or

intrapancreatic gas bubbles

in a collection on CT

• Can be proven by culture or

gram stain of tissue/fluid

Banks P A et al. Gut 2013;62:102-111

Infected Necrosis

• FNA for culture can be performed for

diagnosis but no longer first line

– Infected necrosis no longer an immediate

indication for invasive intervention

– Intervention is usually delayed to 4 weeks after

onset of disease

– Treatment dictated by clinical deterioration and/or

imaging, rather than positive FNA culture

– Consider FNA if suspicious for fungal

superinfection that is not responding to therapy

Acute Pancreatitis timeline

Interstitial

Edematous

Pancreatitis

Acute

Peripancreatic

Fluid Collection

Pseudocyst

Necrotizing

Pancreatitis

Acute Necrotic

Collection

Walled Off

Necrosis

Acute

Pancreatitis

0

Time (weeks)

4

Pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid

collections in AP

• Acute peripancreatic fluid collection (APFC)

– No defined wall, homogeneous, resolve

spontaneously

• Pseudocyst

– Well defined wall, no solid material

• Acute necrotic fluid collection (ANC)

– Contains variable amounts of fluid and necrotic tissue

– May be associated with disruption of the PD

• Walled-off necrosis (WON)

– Mature, encapsulated collection of pancreatic and/or

peripancreatic necrosis with a well defined

inflammatory wall

Zaheer et al. Abdominal Imaging. 2012

Acute peripancreatic fluid collection (APFC)

• APFC in the left anterior

pararenal space (white

arrows showing the borders)

• Confined by normal

peripancreatic fascial planes

• No defined wall

• Homogeneous

• Resolve spontaneously

• No associated peripancreatic

necrosis.

• Seen within the first 4 weeks

• Adjacent to pancreas (no

intrapancreatic extension)

Banks P A et al. Gut 2013;62:102-111

Copyright © BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & British Society of Gastroenterology. All rights reserved.

Acute necrotic collection (ANC)

• collection containing variable

amounts of both fluid and

necrosis associated with

necrotizing pancreatitis

• Occurs only in the setting of

acute necrotizing pancreatitis

• No definable wall encapsulating

the collection

• Location—intrapancreatic

and/or extrapancreatic

Thin white arrows -- heterogeneous collection in the

region of the neck and body of the pancreas, without

extension in the peripancreatic tissues.

Copyright © BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & British Society of Gastroenterology. All rights reserved. Banks

P A et al. Gut 2013;62:102-111

Pseudocysts

•

•

•

•

•

•

Encapsulated collection of fluid

Well defined inflammatory wall

Usually outside the pancreas with

minimal or no necrosis

4 weeks after onset of interstitial

edematous pancreatitis

Homogeneous fluid density

No non-liquid component

White arrows -- well defined enhancing rim

White stars -- normal enhancing pancreas.

Copyright © BMJ Publishing Group Ltd & British Society of Gastroenterology. All rights reserved.

Banks P A et al. Gut 2013;62:102-111

Walled-off necrosis (WON)

• Mature, encapsulated collection of

pancreatic and/or peripancreatic

necrosis

• Well defined inflammatory wall.

• >4 weeks after onset of

necrotizing pancreatitis.

• Heterogeneous with liquid and

non-liquid density with varying

degrees of loculations (some may

appear homogeneous)

• Well defined wall, that is,

completely encapsulated

• Location—intrapancreatic and/or

extrapancreatic

Clinical case

• 55 yo woman presents with acute gallstone pancreatitis with the CT

showing pancreatic necrosis. She has ongoing pain and nausea

and enteral nutrition is initiated due to inability tolerate oral intake.

She develops fever of 38.9 on day 7. She is hemodynamically

stable with a heart rate of 92, BP 130/74 and O2 sat 98% on RA.

Leukocytosis (WBC=14,000/mm3), normal hepatic function and

BUN/creatinine. Repeat CT scan of abdomen shows non-walled off

pancreatic necrosis and CT guided FNA is performed. Gram stain of

FNA shows gram-negative rods. Which of the following is the most

appropriate management at this point?

– A. Refer the patient for prompt surgical necrosectomy.

– B. Refer the patient to IR for percutaneous drainage.

– C. Initiate therapy with IV imipenem and continue to observe the patient

for signs of organ failure and hemodynamic instability.

– D. Refer the patient for endoscopic transgastric drainage.

– E. Switch the patient’s route of nutrition support to parenteral.

C. Initiate therapy with IV imipenem and continue to observe the patient for

signs of organ failure and hemodynamic instability.

• The patient has infected pancreatic necrosis that

is not well walled off. Importantly, the patient is

hemodynamically stable without organ failure.

• While many patients will eventually need some

type of drainage (surgical, percutaneous or

endoscopic), the current preferred strategy is to

initiate IV antibiotics and delay the drainage

procedure as long as the patient condition is

stable, allowing the necrosis to become organized

(walled off).

Initial management

• Early aggressive intravenous hydration!!!

IV hydration

• Aggressive hydration, 250-500 ml/hr of isotonic

crystalloid solution should be given to all patients

unless significant cardiovascular or renal disease

• Some recommend 5-10 ml/kg/hr

• After resuscitation goals are met, can decrease rate

• Most beneficial in first 12-24h, may have little benefit

after this

• For hypotension or tachycardia, boluses may be

required

• LR is generally preferred

• Reassess fluid requirements every 6h.

• Goal is to decrease BUN

Clinical case

• 65 yo male admitted with severe abdominal pain, fever, nausea and

vomiting. On exam he is febrile, with stable vitals. Upper abdomen

is diffusely tender, with rebound and absent bowel sounds. Left flank

ecchymosis is present. Serum amylase and lipase are elevated.

After aggressive fluid resuscitation, a contrast CT scan on day 2 of

illness demonstrates an edematous pancreas with nonenhancement

of about 30% of the gland and multiple peri-pancreatic fluid

collections. In terms of management, which of the following

statements about nutrition is correct?

– A. TPN and enteral nutrition result in similar metabolic complications.

– B. Nutritional support is indicated in patients with mild pancreatitis to

reduce complications.

– C. TPN is associated with mortality reduction in acute pancreatitis.

– D. Enteral nutrition is the preferred route for nutritional support in

patients with severe acute pancreatitis.

– E. Pancreatic necrosis contraindicates enteral feeding.

Nutrition therapy

• In mild AP, oral feedings can be started

immediately if no nausea/vomiting, and if pain is

improving

• In mild AP, low-fat solid diet appears as safe as a

clear liquid diet

• In severe AP, enteral nutrition recommended to

prevent infectious complications

• Parenteral nutrition should be avoided unless

enteral route not available, not tolerated, or not

meeting caloric requirements

• Nasogastric and nasojejunal feedings appear

comparable

D. Enteral nutrition is the preferred route for nutritional support in patients with

severe acute pancreatitis.

• Patients with mild pancreatitis can be treated with hydration

alone.

• Initial feeding with a low-fat diet is safe and may reduce the

duration of hospitalization compared to clear liquid diet in

patients with mild pancreatitis.

• Multiple studies have demonstrated that enteral feeding is

safe and tolerated in acute pancreatitis.

• Additionally, enteral feeding may preserve gut barrier function

and prevent translocation of bacteria, which are implicated in

pancreatic infections.

• A meta-analysis of the existing literature has demonstrated

improved outcome with enteral feeding compared with

parenteral feeding, with less infectious complications,

reduced cost and better glycemic control.

ERCP in acute pancreatitis

• Patients with AP and cholangitis should

undergo ERCP within 24h

• In biliary pancreatitis without cholangitis,

timing of ERCP unclear

• Screen for choledocholithiasis with MRCP

(or EUS) if suspicion is high

Antibiotics in AP

• Routine use of prophylactic antibiotics in

severe AP is NOT recommended

• Use of antibiotics in sterile necrosis to

prevent infected necrosis is NOT

recommended

• Probiotic prophylaxis is NOT

recommended

Antibiotics in AP

• Infected necrosis

– Suspect in pt with pancreatic necrosis who

deteriorates or fails to improve after 7-10 days

– Empiric antibiotics after blood cultures vs CTguided FNA

– Carbapenems, quinolones and metronidazole

are best

– Routine use of antifungal agents along with

antibiotics not recommended

Infected necrosis

• Routine percutaneous FNA of peripancreatic collections

to detect bacteria is not indicated, because clinical signs

(i.e. persistent fever, increasing inflammatory markers)

and imaging signs (i.e. gas in peripancreatic collections)

are accurate predictors of infected necrosis in the

majority of patients.

• Although the diagnosis of infection can be confirmed by

FNA, there is a risk of false-negative results.

Indications for intervention in

necrotizing pancreatitis:

• 1) Clinical suspicion of, or documented

infected necrotizing pancreatitis with clinical

deterioration, preferably when the necrosis

has become walled-off,

• 2) In the absence of documented infected

necrotizing pancreatitis, ongoing organ failure

for several weeks after the onset of acute

pancreatitis, preferably when the necrosis

has become walled-off.

Indications for intervention in sterile

necrotizing pancreatitis

• 1) Ongoing gastric outlet, intestinal, or biliary obstruction due

to mass effect of walled-off necrosis (i.e. arbitrarily >4-8

weeks after onset of acute pancreatitis)

• 2) Persistent symptoms in patients with walled-off necrosis

without signs of infection (i.e. arbitrarily >8 weeks after onset

of acute pancreatitis)

• 3) Disconnected duct syndrome (i.e. full transection of the

pancreatic duct in the presence of pancreatic necrosis) with

persisting symptomatic (e.g. pain, obstruction) collection(s)

with necrosis without signs of infections (i.e. arbitrarily >8

weeks after onset of acute pancreatitis)

Interventions in AP

• In general, interventions in necrotizing

pancreatitis should be delayed until all

fluid collections have become walled-off,

at least 4 weeks from presentation

The role of surgery

• In mild gallstone pancreatitis, cholecystectomy should

be performed before discharge to prevent recurrence

• In necrotizing biliary AP, cholecystectomy should be

deferred until active inflammation subsides and fluid

collections resolve or stabilize after 6 weeks

• In patients with biliary pancreatitis who have

undergone sphincterotomy and are fit for surgery,

cholecystectomy is advised, because ERCP and

sphincterotomy prevent recurrence of biliary

pancreatitis but not gallstone related gallbladder

disease, i.e. biliary colic and cholecystitis

Role of surgery cont’d

• Asymptomatic pseudocysts or fluid

collections do not require intervention

• In stable infected necrosis, drainage should

be delayed preferably >4 weeks to allow

liquefaction of contents and development of a

wall around the necrosis

• In symptomatic patients with infected

necrosis, minimally invasive methods of

necrosectomy are preferred to open route

Video-Assisted Retroperitoneal

Debridement (VARD)

• Involves using a 5 cm subcostal incision

and limited direct debridement followed by

subsequent video-assisted debridement

• Morbidity and mortality of 24%-54% and

0%-8% respectively

• Usually only requires one session/patient

Freeman et al. Pancreas 2012; 41 (8): 1176-

Van Brunschot S et al. Clin Gastroenterology and

Hepatology 2012; 10:1190-1201

• Management of pseudocysts

Pseudocysts

• Pseudocysts complicate 10-26% of acute

pancreatitis cases

• Also present in 20-40% of chronic pancreatitis

cases

• Most common after acute exacerbations of chronic

pancreatitis

• Usually nonpalpable on physical examination

• Like arise from disruption of main pancreatic duct

or intrapancreatic branches without significant

parenchymal necrosis

• High amylase levels in fluid

Indications for intervention

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Persistent pain

Gastric or duodenal obstruction

Biliary obstruction

Ascites

Pleural effusion

Enlarging size on serial imaging

Evidence of infection or bleeding

Possible pancreatic cystic malignancy

Van Brunschot S et al. Clin Gastroenterology and

Hepatology 2012; 10:1190-1201