Troubling narratives conference_K Poursanidou_20 June 2014

advertisement

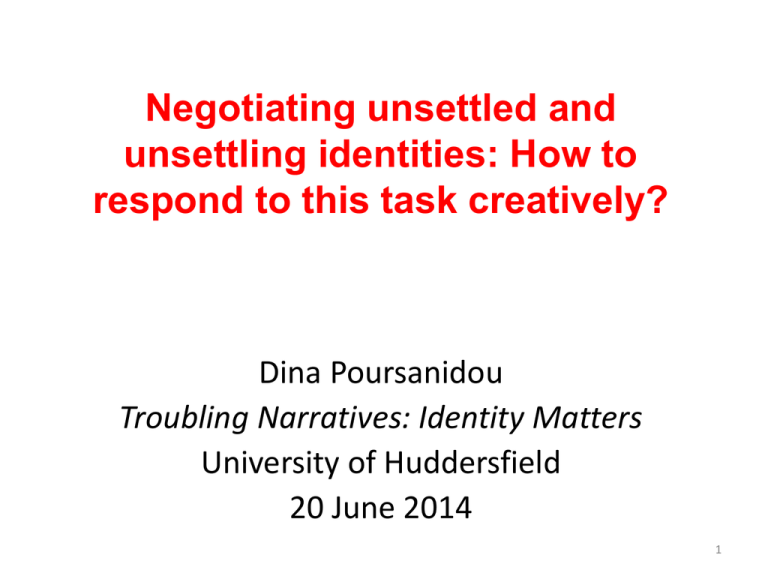

Negotiating unsettled and unsettling identities: How to respond to this task creatively? Dina Poursanidou Troubling Narratives: Identity Matters University of Huddersfield 20 June 2014 1 My purpose in this paper • Use a piece of qualitative auto-ethnographic research to reflect critically on unsettled/troubled and unsettling/troubling identities, and on the possibilities of negotiating such identities creatively • The research in question has sought to explore the unremitting identity and other struggles implicated in the task of constructing and negotiating my double identity as an academic researcher and a mental health service user-a task full of complexities, challenges, contradictions and ambiguities 2 What I tried to do in my autoethnographic research • Use my story to ask wider questions about the challenges and support/development needs of mental health service users actively involved in University-based mental health research; using autobiography to inform critical social analysis • Use my lived experience as data to problematise mental health service user involvement in University-based research • The reality of involving mental health service users in University-based research is a lot more complex, messy, troubled, and full of contradictions compared to the respective rhetoric • A critical understanding of the manifold and complex ways in which affective/emotional and socio-cultural dimensions of experience interplay in shaping mental health service user involvement in University-based research • My story/auto-ethnography first presented in June 2011; continually evolving, developing; reinvigorated through discussions with different audiences • Not a coherent, consistent, linear, seamless and complete story • A story characterised by contradictions, ambiguities, complexities, 3 interruptions, fragmentation and open-endedness Looking for an Epistemology/Theory of knowledge • ‘Using researcher subjectivity as an instrument of psychosocial knowing’ (Hollway, 2011) • Privileging the concepts of intuition and emotional experience as knowledge tools • Tolerating the absence of a consistent and linear story… tolerating muddle…allowing for imagination • A theory of knowledge consistent with experiences radically outside rational language and discourse (e.g. madness; trauma); How to communicate the unspeakable/ineffable? • Non-positivist, psychoanalytically informed theory of knowledge – Wilfred Bion • An epistemology capturing the embodied, affective encounters that occur between subjectivity and socio-cultural life 4 A psychosocial framework of analysis • A psychosocial framework of analysis ‘ attempts to move from lesser (reductive: purely psychological or purely sociological) to greater understandings (more complex: recognizing both psychically unique and socially contingent elements) of social phenomena’ (Jefferson, 2008) • ‘Conceptualizing the psychosocial subject non-reductively implies that the complexities of both the inner and the outer world are taken seriously. Taking the social world seriously means thinking about questions to do with structure, power and discourse…Taking the inner world seriously involves an engagement with contemporary psychoanalytic theorizing because only there, in our view, are unconscious as well as conscious processes, and the resulting conflicts and contradictions among reason, anxiety and desire, subjected to any sustained, critical attention’ (Gadd and Jefferson, 2007) • Intrapsychic, intersubjective, institutional and macro societal/political and economic domains of experience • Psychosocial influences that have combined in shaping my journey from Willow Ward back to academia 5 Looking for a Methodology • Autobiographical material Forbidden Narratives: Critical autobiography as social science (Church, 1995) • Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity-Researcher as Subject (Ellis and Bochner, 2000) • Personal, intimate, embodied writing • First person voice • Auto-ethnography connects the personal/self to the cultural/culture (Ellis and Bochner, 2000) 6 Why attracted to autoethnography? I My attraction to autoethnography relates to the capacity to see the complex interaction/interplay of the multiple dimensions of experience, ie intrapsychic/affective, intersubjective, institutional and macro-societal/political/economic, through looking at the interaction of self and culture. Perhaps seeing this complex interaction may be a step towards looking critically at and even going beyond often unhelpful dualisms such as individual/social, micro/macro, psychological/societal. Our biographies are inevitably social for example. 7 Why attracted to autoethnography? II Using myself as an instrument of knowing and understanding … Making myself vulnerable… With the conviction that… Scholarship ‘that doesn’t break your heart just isn’t worth doing’ (Behar, 1996, The Vulnerable Observer – Anthropology that Breaks Your Heart) Wanting to do scholarship in which ‘the blood is left in’ (Moriarty, 2013)… 8 Data sources • My reflexive research journal • Reflexive notes from individual psychotherapy sessions that I attended as a client and where the challenges of being a researcher service user were worked throughincluding email communication with my psychologist • Artwork and creative writing reflecting my struggle to make sense of my mental health crisis and recover • Email communication with my psychotherapist and with other service user researchers/academics • My mental health/care notes from 2009 (Jan-April) • Informal conversations with other Service User Researchers • Presentations and discussions of my continually developing auto-ethnography with different audiences 9 Troubling language/self-identifications/identity politics I • Researcher Service User? • Service user? Used secondary mental health services from July 2008 to March 2013 • Consumer? The neoliberal discourse of ‘consumer participation’ in planning and evaluating health/mental health services and in health/mental health services research Consumer choice, control and power ‘The consumer as king’ (Shaw, 2009) • Psychiatric Survivor? • Distressed or disabled? Psychosocial disability (USA) • Person with lived experience Lived experience of what? 10 11 Expert by Experience? (a) I avoid identifying myself as an ‘expert by experience’ - a common label nowadays for mental health service users which I question. If I was to be called an 'expert by experience', what exactly would I be an expert on? On compulsory hospitalisation (sectioning) and how it can destroy one's confidence perhaps? But having had an experience of sectioning (my own experience) does not necessarily make me an expert on detention. It just means that I have lived through detention and I have the experiential/embodied knowledge that stems from that, so when I talk about detention it is not just on a cognitive/academic/theoretical level using knowledge that I have acquired from books, but on an affective, visceral, deeper level as well. Does this make me an expert? I am not sure... Or would I be an expert on madness? But how can one be an expert on madness if madness is something that cannot be known and understood in its entirety, something that cannot be easily articulated? And are we not all experts through our experiences? if so, why would we need the presumed epistemological privilege of being a mental health service user to claim such expertise? (From email communication with a service user academic in USA) 12 Expert by Experience? (b) Furthermore, raw experience (embodied, affective/emotional experience ) is not, in my view, automatically translated into knowledge and expertise...I think raw emotional experience needs to be processed and detoxified and reflected upon in order to become available for thought, in order to become knowledge... so, experience does not equal expertise...On the other hand, I do recognise and value the collective experiential knowledge and expertise that emerges from the psychiatric survivor movement – but I would not call myself ‘an expert by experience’. Finally, apart from ‘experts by experience’ mental health service users often identify themselves as ‘Service User Experts’ ,‘Expert Patient Trainers etc…I feel quite uncomfortable when I see what I perceive as the selfserving 'careerism' of those professionalised lay experts , and the commodification of personal trauma that seems to go with it a lot of the time - although I can understand very well how a ruthlessly competitive job market forces mental health service users to have to ‘sell' their stories of 'lived experience' of mental distress as a qualification for employment...I wonder how immune to that I am myself. (From email communication with a service user academic in USA) 13 Troubling language/self-identifications/identity politics II • Ex-inmate (David Reville)? • Mad-identified (David Reville)? • Mad Pride – Romanticisation of mental distress? • Where is home for me? Academic Research or Psychiatric Survivor Movement? 14 A liminal space in-between… • Home for me = a liminal space in - between academic research and psychiatric survivor movement • ‘An in-between space/territory in which cultures mix and interact to create new hybrid forms’ (Urban social geography glossary) • ‘Living in the borderlands; writing in the margins’ (Grant, 2007) • [Learning To ] Walk Between Worlds (Church, 2001) • Hybrid identity (Grant) – academic researcher + psychiatric survivor + mental health professional • A double identity of an academic researcher and a mental health service user– ‘Breaking the rules of Academia’ – Transgressive identity (Grant) • Being able to theorise one’s own lived experience… • Blending first person experiential accounts where ‘the blood has been left in’ (Moriarty, 2013) with ‘properly academic’ (i.e. critically detached , ‘objective’ and rigorous) commentaries… • ‘The lack of clear boundaries involves transgression and threat’ (Jones, 2012) • A liminal identity space- a difficult, unsettling and contested space; it can 15 also open up creative and subversive possibilities… Liminality and trouble… ‘I am here because I am a woman of the border: between places, between identities, between languages, between cultures, between longings and illusions, one foot in the academy and one foot out’ (Behar, 1996, p. 162) ‘Troubled subject positions’ (Wetherell, 1998) ‘Unsettling relations’ between traditional (non service user) University researchers and mental health service user researchers ( Bannerji et al., 1991; Church, 1995) 16 Paradoxes of service user involvement in academic research as lived contradictions • Mental health service user involvement in academic research as ‘a paradoxical space’ (Rose, 1993; Spandler, 2009); Paradoxes as ‘lived contradictions’ (Cresswell and Spandler, 2013) • The paradox of (women) occupying several social spaces (e.g. insider and outsider positionings) simultaneously (Rose, 1993) • A past diagnosis of ‘psychotic depression’, detention under a section, and use of secondary mental health services got me a job – The ‘Mental illness as an advantage’ paradox; ‘For some academic researchers, mental illness can be an advantage’ (The Guardian) • Being a mental health service user in academic research -privileged as having ‘unique insights’, ‘valuable service user knowledge’, ‘expertise by experience’; BUT the mental health service user identity is a stigmatising , devalued , ‘spoiled’ (Goffman, 2009) social identity I have often wished to disown • Mental health service user involvement in academic research: its potential simultaneously for both emancipation and appropriation/cooptation/assimilation (Beresford, 2002) 17 Paradoxical space 18 Service user involvement as appropriation/assimilation/co-optation ‘Service user involvement and participation practices have become so incorporated that they are best viewed as part of the overarching system connecting psychiatric surveillance with societal governance’ (Cooke and Kothari, 2001) 19 Editorial - Asylum Toronto ‘The market-driven principles of mental health care under neo-liberalism have never been more obvious. With patients situated as consumers in a mental health system defined by concepts of risk, dominated by Big Pharma, and driven by profit, there is little acknowledgement of rights let alone any substantial resistance to a rapidly expanding mental health system. Worse, many so-called ‘mental health activists’ have become consumed by assimilationist strategies, opting to promote the idea that change can be delivered from within, and advocating peer support and continuing professional education as the new solution to age-old systemic problems: coercion and forced treatment, racism and white supremacy, poverty, homelessness and social isolation … When did we start seeing the mental health care ‘system’ in the likeness of a group of naïve and idiotic professionals – doctors, nurses, health practitioners, policy makers – who are at the same time well-intentioned and unknowing? And when did we decide that a seat at their table or a moment of their time would make even a bit of difference? What led us to believe that there was power in disclosing our stories, our experiences and our secrets? When did we start deluding ourselves that we mattered that much – or at all, in truth? It would be laughable if it weren’t so pervasive. And dangerous.’ (Asylum - The magazine for democratic psychiatry, Volume 20, Number 4, 2013, p.3))20 Recovering Our Stories: A Small Act of Resistance ‘We all have stories. Many of our stories are deeply personal. Some of our stories are painful, traumatic, hilarious, heroic, bold, banal. Our stories connect us—they reflect who we are and how we relate to one another. Stories are extremely powerful and have the potential to bring us together, to shed light on the injustice committed against us and they lead us to understand that not one of us is alone in this world. But our stories are also a commodity—they help others sell their products, their programs, their services—and sometimes they mine our stories for the details that serve their interests best—and in doing so present us as less than whole. - Becky McFarlane, Recovering Our Stories event, June 2011’ (Costa et al., 2012, p. 86) 21 Asylum - The magazine for democratic psychiatry, Volume 20, Number 4, 2013 Cartoon by Merinda Epstein 22 Park House, North Manchester General Hospital Willow Ward: The culmination of my mental health crisis (July 2008-June 2010) Detained in Willow Ward under MHA (January – April 2009) 23 Park House, NMGH- Entrance I used to hate the sight of this entrance… 24 Willow Ward – How my worst nightmare came true… • When I was detained in hospital, I was treated as somebody with diminished capacity and insight • Me - As portrayed in my Care Records (January 2009 -April 2009): “..dishevelled, retarded, highly agitated and characterised by suicidal ideation, lethargic and far from mentally alert, incontinent and odorous, occasionally subjected to physical restraint. ..” “Possibly needing ECT treatment due to treatment-resistant severe psychotic depression” • A huge blow to my confidence and a source of profound feelings of humiliation and shame, as well as a source of a deep sense of failure, unfairness/injustice and stigmatisation- all acutely disempowering emotions 25 Fearful Expression Induced By Electricity, Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne (de Boulogne) Fear –Acute anxiety - Panic attacks 26 Melancholy, Edvard Munch Severe and enduring ‘psychotic depression’ Complete lack of motivation and interest in life Acute hopelessness and persistent suicidal thoughts 27 Terror, Alfred Kubin Feeling terrified in Willow Ward 28 Oppression, Alfred Kubin Having my confidence crushed 29 The Pursued One, Alfred Kubin Persecutory anxieties – Paranoid thoughts – ‘Psychotic symptoms’ 30 The Other Side, A. Kubin (1908/2000) – Madness? A novel that tells of a dream kingdom which becomes a nightmare, of a journey to a mysterious city created deep in Asia, which is also a journey to the depths of the subconscious – ‘a sort of Baedeker (Guidebook) for those lands which are half-known to us’, as Kubin himself called it. 31 From Willow Ward back to Academia… How does one go from Willow Ward back to Academia? How does one go from such harrowing states of mind back to academic research? How does one go from ‘the Other Side’ back to Academia? 32 Re-entering Academia: challenges I • Low confidence, performance anxiety, perfectionism/unrelenting standards, self-doubt • Difficulties with delivering work on time and with team work; harsh criticism • Time management/reliability (being late for meetings) • Colleagues’ lowered expectations of me; unwitting prejudices; hard work to restore trust in my abilities • Colleagues’ frustration and anger; caring, sensitive people • What do colleagues-academic researchers see? Somebody with a broken mind or the researcher? • What do other service users see? Because of my academic research background, not a bona fide service user 33 Re-entering Academia: challenges II - As a result of my very severe and persistent depression, lasting a couple of years, I lost what had always been a vital source of self-esteem and recognition for me, as well as an essential tool for being an academic researcher-my capacity to excel intellectually/academically and think creatively about complex phenomena. I could not think clearly, I could not concentrate and retain information, I could not process language, I could not read and understand what I was reading, I could not be intellectually creative. My head was constantly heavy and cloudy due to the potent medication I was prescribed- especially when I was on copious amounts of it. I was off work for nearly 2 years and thus away from opportunities for intellectual stimulation for far too long. Hence, re-entering academic research involved re-learning and re-gaining all these vital cognitive skills and abilities that I had lost. - In my Service User Researcher role, I am expected to be constantly in touch with and use my service user subjectivity, survivor knowledge and emotional (lived) experience as an instrument of knowing and understanding- a particularly challenging task. Survivor knowledge, mad knowledge is difficult, unsettling and troublesome knowledge. How can one bear continuous contact with the inchoate (madness) and the discomfort and terror it generates? How can one continuously tolerate the memory of the collapse of rationality and of the uncertainty of not knowing? - For example, in the context of my Service User Research Fellow post in UCLan, I interviewed users of mental health services about their experiences of independent mental health advocacy whilst in compulsory treatment. The traumatic stories the interviewees told me brought back memories of my own personal traumas and I often struggled in my efforts to achieve a balance between showing empathy and maintaining my emotional boundaries, avoiding over-identification. (From my reflexive research journal) 34 Re-entering Academia: challenges III • The wider neoliberal political and economic environment where Universities operate in England (Sparkes, 2013) -Government cuts in research funding -Acutely competitive research labour market -Pressures to deliver research outputs within tight timescales • Structural and institutional barriers to meaningful mental health service user researcher involvement -Succession of temporary, very short-term and part-time research contracts; financial uncertainty -Obstacles to career progression (no lead researcher roles; no mental space for writing for publication) -Unemployment -Lack of consistency in occupational health clearance practices for mental health service user researchers – even within the same locality/University Faculty (Manchester) -Current changes in the wider institutional and policy context with regard to Patient and Public Involvement in Research (i.e. changes in the NIHR infrastructure/Clinical Research Networks; ‘dismantling’ of MHRN); loss of vital sources of support and local knowledge? loss of longstanding relationships and resources? uncertainty for mental health service user researchers regarding critical sources of support to do with development needs? 35 Re-entering Academia: challenges IV • Career progression/career pathways and career development support for mental health service user researchers • How many mental health service user researchers get to be Principal Investigators in research studies? The existence of ceilings even for the most qualified and experienced service user researchers • How well are mental health service user researchers supported and mentored in their jobs? What about the development, training, support and employment needs of mental health service user researchers? • Job insecurity (very short contracts or just Honorary contracts) 36 Re-entering Academia: challenges V • Structural, institutional and relational barriers to meaningful mental health service user involvement in academic research • Internal/affective barriers to meaningful mental health service user involvement in academic research – the most difficult to tackle for me… -Fear of relapse -Having to fight critical and disempowering internalised messages from mental health professionals; fighting self-stigma ‘What makes you think you can go from Willow Ward to a research job? You were very ill with psychotic, treatment resistant depression, possibly needing ECT! It can happen again!’ -Self-sabotage and survivor guilt 37 Struggling with Ambivalence… • Ambivalence - a core and often unsettling emotional experience for me in the liminal identity space I inhabit as a mental health service user researcher • Profound ambivalence towards my latest mental health crisis, my mental health service user identity and my mental health service user researcher subjectivity/role itself (huge losses and traumas/biographical disruption/bitterness and grief; opportunities for personal growth and transformation) • Wishing to disown and at the same time to hold on to my mental health service user identity… • The ‘Madness and mad knowledge as a dangerous gift’ paradox the knowledge stemming from my lived experience of mental distress may be an asset, potentially positive and valuable for mental health research BUT at the same time it is something excruciatingly painful that I often wish I did not have! 38 'Blessed are the cracked, for they let in the light’ (Spike Milligan) Spike Milligan (1918 - 2002) - an Irishman; described on his gravestone as 'Writer, Artist, Musician, Humanitarian, Comedian‘; a life-long sufferer from depression; his epitaph reads ‘I told you I was ill’ (http://www.winwisdom.com/ quotes/author/spikemilligan.aspx) 39 Ambivalence Dina: there are people at Start who are brilliant in terms of their talents, and that’s including myself…but because of the mental health stuff they’re compromised in so many areas of their lives…they can’t work, they rely on heavy medication, they can’t travel in public transport, they’re restricted because of their mental health problems…I suppose I feel some bitterness around that because I feel it’s so unfair…and I think I feel that about myself as well…how much I’ve had to struggle to regain my confidence…it’s just twice as hard if you’ve had that load of the mental health thing…I feel privileged that I’ve met these people but there’s a part of me that just feels bitter about the mental health thing…for me and for them I think…when I see how much people are compromised by it, whereas they’ve got amazing potential and talents…I don’t know, I’m not sure about it …whether having had mental health problems has offered me opportunities for change and growth…I have had 20 years of psychotherapy which definitely enabled a great deal of personal development and transformation for me but I often wonder about the huge cost of my 'posttraumatic growth‘… Reflexive notes from therapy session (June 2011) 40 Ambivalence (Recovery ©Daniel Saul-Making Waves) 41 Some hard and troubling questions… • Are Universities genuinely interested in mental health service user/survivor knowledge and involvement in research? • How far can the emancipatory and democratic ideals, and the ethical claims to equality, diversity and inclusion that underpin the discourse of mental health service user involvement in research, be reconciled with the markedly hierarchical, exclusionary and largely non-democratic infrastructures of Academia? • How to do collaborative, relational and participatory work in Academia when individual success and competition dominate? 42 Some creative responses to ‘unsettlement’ • Story-telling in various contexts and fora • My auto-ethnography research ; theorisation of my experience • Dina’s Blog • Asylum magazine collective • Doing art • Individual psychotherapy 43 Asylum: collective action and a sense of community http://www.asylumonline.net http://www.pccs-books.co.uk Dina's Blog on Asylum, the Magazine for Democratic Psychiatry http://www.asylumonline.net/dinas-blog/ 44 Beginnings of recovery? Art in Willow Ward II 45 • • • • • • • • • References Bannerji, H., Carty, L., Dehli, K., Heald, S. & McKenna, K. (1992) Unsettling Relations: The University as a Site of Feminist Struggles, Toronto, Women’s Press Behar, R. (1996) The vulnerable observer: Anthropology that breaks your heart, Boston, Beacon Press Beresford, P. (2002) ‘User Involvement in Research and Evaluation: Liberation or Regulation?’, Social Policy & Society, 1:2, 95-105 Church, K. (1995) Forbidden Narratives: Critical Autobiography as Social Science, London, Routledge Church, K. (2001) Learning To Walk Between Worlds - Informal learning in psychiatric survivor-run businesses: A retrospective re-reading of research process and results from 1993-1999, NALL Working Paper No.20, Network for New Approaches to Lifelong Learning, Toronto, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto Cooke, B. & Kothari, U. (2001) Participation: the new tyranny?, London, Zed Books Costa, L. et al. (2012) ‘Recovering our stories: A small act of resistance’, Studies in Social Justice, Vol 6, Issue 1, 85-101 Cresswell, M. & Spandler, H. (2013) ‘The Engaged Academic: Academic Intellectuals and the Psychiatric Survivor Movement’, Social Movement Studies: Journal of Social, Cultural and Political Protest, 12:2, 138-154 Ellis, C. & Bochner, A. P. (2000) ‘Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject’. In Handbook of Qualitative Research, 2nd ed, edited by N.K.36 Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln, Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage References • • • • • • • • Gadd, D. & Jefferson, T. (2007) Psychosocial Criminology: An Introduction, London, Sage Goffman, E. (2009) Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity, New York, Simon and Schuster Hollway, W. (2011) ‘Psycho-social writing from data’, Journal of Psycho-Social Studies, Vol 5, Issue 1, 92-101 Jefferson, T. (2008) ‘WHAT IS ‘‘THE PSYCHOSOCIAL’’? A RESPONSE TO FROSH AND BARAITSER’ (Commentary), Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 13, 366–373 Jones, N. (2012) ‘Schizophrenia Bulletin, the BJP & the Politics of FirstPerson Accounts’, Ruminations on Madness, 15 August (http://phenomenologyofmadness.wordpress.com/2012/08/15/schizophreniabulletin-the-bjp-the-politics-of-first-person-accounts). Accessed 19 February 2014 Kubin, A. (1908/2000) The Other Side, translated by M. Mitchell, Sawtry Cambs, Dedalus Ltd Moriarty, J. (2013) ‘Leaving the blood in: Experiences with an autoethnographic doctoral thesis’. In Contemporary British Autoethnography, edited by N. P. Short, L. Turner & A. Grant, Rotterdam, Sense Publishers Rose, G. (1993) Feminism and Geography: The Limits of Geographical Knowledge, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press 47 References • • • • • • Shaw, E. (2009) ‘The consumer and New Labour: the consumer as king?’ in Simmons, R., Powell, M. and Greener, I. (Eds.) The Consumer in Public Services – Choice, Values and Difference, Bristol, The Policy Press Short, N., Grant, A. & Clarke, L. (2007) ‘Living in the borderlands; writing in the margins: an autoethnographic tale’, Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14, 771–782 Spandler, H. (2009) ‘Spaces of psychiatric contention: A case study of a therapeutic community’, Health & Place, 15, 672–678 Sparkes, A. C. (2013) ‘Qualitative research in sport, exercise and health in the era of neoliberalism, audit and New Public Management: understanding the conditions for the (im)possibilities of a new paradigm dialogue’, Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 5:3, 440-459 Tickle, L. (2009) ‘For some academic researchers, mental illness can be an advantage’, The Guardian, 25 August (www.theguardian.com/education/2009/aug/25/mental-health-academicresearch). Accessed 19 February 2014 Wetherell, M. (1998) ‘Positioning and interpretative repertoires: Conversation analysis and poststructuralism in dialogue’, Discourse and Society, 9(3), 387–412 48 Contact Me! Dr Dina Poursanidou Honorary Research Associate/Service User Researcher University of Manchester Centre for Women's Mental Health Institute of Brain, Behaviour and Mental Health Manchester M13 9PL Email:konstantina.poursanidou @manchester.ac.uk Mobile: 0044 (0) 7792358092 49