Driven and Not Looking Back: A Qualitative Analysis of Students

advertisement

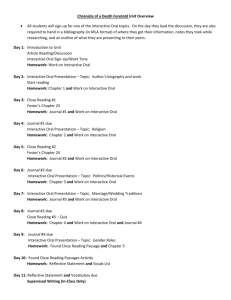

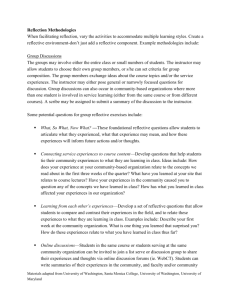

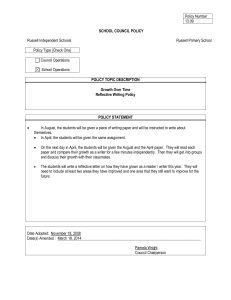

ASSESSING STUDENT TEACHER’S REFLECTIVE THINKING AND PRACTICE Dr. Loren Weybright Assistant Professor of Elementary Education Metropolitan College of New York New York, New York lweybright@mcny.edu 1 Central Questions What reflective thinking skills are revealed in graduate student teacher’s journals, lessons and action research projects (Constructive Action projects )? How can the instructor best foster reflective thinking in students teacher’s investigations into their own learning and teaching? 2 Literature Review Dewey (1933) observed that reflective thinking enabled teachers to consider the outcome of their actions in light of their past experiences. Without that reflection, teachers would mindlessly repeat their prior actions. Schon (1987), building on Dewey and others, proposed a design for educating the reflective practioner where the primary task for novice (and his/her coach or supervisor) was to reflect on his/her own actions and the underlying assumptions that prompt those actions. 3 Literature Review (continued) Schon (1987) also called for research on coaching (field supervision) and on learning by doing in the practicum. The professional schools must also determine the relationship between courses offered and the needs of the beginning teacher in the field. Taggart & Wilson (1998) define reflective thinking as the process of making informed and logical decisions about one’s own practice, then assessing the consequences of those decisions. 4 Participants Data were obtained from all the graduate students in one cohort, totaling 14 women candidates, during their first semester of student teaching, Spring 2006 Semester. Age range: Mid-20s to late 30s Ethnic origins:, 7 African-Americans, 5 European-Americans and 2 Hispanics. Work experience: All had some experience with groups of children prior to admission. Careers: Part-time teaching, business, media, and the health and human service professions. Two students were admitted upon graduation from BA programs, without prior careers. 5 Program Description This study was part of the documentation of the one-year M.S. in Education Program, leading to Childhood Education Certification (Gr.1-6), at Metropolitan College of New York, a small private college located in lower Manhattan. 6 Program Description (Continued) Students enter program as a cohort, following the 3semester program as a group. Students design and complete a Constructive Action (CA) project each semester as part of their integrative seminar. The action research projects during their first semester of student teaching, focused on a series of lessons taught in literacy or mathematics, are designed to integrate course work with field experiences. 7 Procedure This qualitative case study examines students’ critical thinking as revealed in lessons, journals, and their Constructive Action Projects. Data was collected from January through April 2006. The seminar and student teaching supervision was designed by this instructor to provide a forum for students to discuss and share their written and oral reflections about their practice teaching, and to solve problems in their practice. 8 Procedures (Continued) Used multiple sources of data, following Cochran-Smith and Lytle’s (1993) typology for teacher research: Journals: Students completed at least six journals, describing and reflecting on their student teaching. Instructor critiqued each journal and students revised as necessary. (See Appendix C in paper copy for Journal Guidelines.) First and last journals analyzed for level of critical thinking skills. (Appendix A: Reflective Thinking Scale from Sparks-Langer and Colton, 1991. Supervisor’s Observation of Lessons: Journals included reflections on 3 observed lessons, allowing for student and instructor’s review of reflective practice. 9 Procedures (Continued) Constructive Action (CA) Project: Each student designed a small action research study to document their student teaching and children’s responses in a specific curriculum area. Examples of topics include: A case study of a second grade girl’s beginning reading skills. Second graders’ comprehension of the “main idea” in non-fiction. Documenting first graders’ writing skills, using graphic organizers and accountable talk. 10 Procedures (Continued) Essays. The six journals on the student teaching in one focused topic were summarized into an essay for the Results section. Students were directed through a descriptive review or analysis of their journals to identify patterns in children and teacher behaviors and to integrate their findings with other course work and related research. 11 Procedures (Continued) Reflective Thinking Scale: Sparks-Langer & Colton’s (1991) seven-point scale: 1. No Description, 2. Layperson’s description, 3. Identified pedagogical strategies, 4. Explanations only used personal reference, 5. Explained pedagogical principles, 6. Added context of classroom, 7. Ethical/moral considerations. 12 Procedures (Continued) Reflective Practice—Work Sample Analysis: Review of children and student teachers’ work samples, using protocol adapted from Pat Carini’s structured inquiry process, the Descriptive Review (Himley & Carini, Eds., 2000). A example of work sample analysis follows: 13 Procedures: Work Sample Analysis Protocol for Analysis of Child or Adult Work Samples*: 1. Presenter introduces child/teacher work sample, providing context of the assignment and author. 2. Facilitator begins first round, asking each group member for a response: What do you see? 3. Facilitator records group responses on chart or projects on classroom computer/screen. 4. Facilitator categorizes responses. 5. Facilitator asks, in second and third round: What else do you see, or what can be inferred? 6. Facilitator and group summarizes responses and identifies next steps 14 Work Sample Analysis (Continued) Further questions to ask of the work: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. What skills/knowledge do you see in evidence? What did the teacher expect of the students? What did the teacher/child appear to value? What 'in the work connects to students' real life? What can we assume about the student's thought process? The teacher's? *Adapted from Coalition of Essential Schools: http://search.essentialschools.org/cgi-bin/htsearch 15 Work Sample Analysis (Continued) Work Sample: “Shauna,” a first grader in an urban school, as documented by Mr. M., Student Teacher, Spring, 2007: Shauna wrote in her journal, 11/06: “Shauna Class 1-214 “Today we are going to fancy up our writing [She writes in carefully formed print, with uneven spacing and letter sizing, but with proper capital “T” and period.] 16 Work Sample Analysis (Continued) Shauna work sample, 4/07: Independent reading assignment: What was the problem and how did they solve it? “Emma had a problem. She “climend” a rope and ladder but it did not work when “sping” came she got a rope and the ladder and boxes and Sam’s Trampoline & her Problem was gone.” Illustration shows tree, rope ladder and girl. 17 Work Sample Analysis (Continued) Group Analysis of Shauna’s 2 work samples, first and second rounds, categories in bold: For follow up: “fancy up” May have been teacher’s language. Mr. M. will ask Shauna later. Attention to detail: content, shaping & spacing of letters Clearly identified “Problem” and “Problem gone” Shows improvement over time in: Response to assigned task, attention to detail, quality of printing, depth of conceptualization of story. Shauna reveals herself as a capable, above average first grader. 18 Work Sample Analysis (Continued) Mr. M. took the group analysis of Shauna’s work back to his classroom to advise his instruction, and the composition of his final project report (Constructive Action document). 19 Results Reflective Thinking Levels: Preliminary results indicate a steady increase in level of reflective thinking in student journals and student teaching. (See Table 1.) Wide range in reflective thinking levels, from several students’ lows in the 3-5 range, to highs in the 6-7 range. Modest gains at top of range and a 2.5 step gain among those students starting at level 3. 20 Results—Content Analysis Used contextual factors when explaining pedagogical principles: “Although she reads and speaks well, it is obvious from observing her that reading and writing are not her preferred activities, and it is not likely that they are actively encouraged at home. Without this reinforcement, continued progress will be very difficult.” (“Iris,” CA 2006.) 6/14 students achieved Level 6 on Sparks-Langer & Colton Reflective Thinking Scale. 21 Results—Content Analysis Integrates reflections with developmental/pedagogical theories: “The thing that stunned me most was the peer mediation that occurred in the group of children, and how one group member was able to take of the direction of the group.” (“Tamara,” Second journal. Peer mediation was the subject of her CA in the previous semester.) 13/14 students made references to theories and practice from other research—a requirement for the CA. 22 Monica’s Summary: First grader’s study of community helpers with read-aloud texts and writing In sum, I chose to organize the lessons with read-alouds, webs and interactive writing because the children were already accustomed to this format of learning. The children learned about community helpers, as seen by: Drawing and listing tools each community helper uses, by identification of a list of community helpers in their neighborhoods, by the Community Helper books each child made. I learned that we as teachers need to be flexible and go back to the drawing board if there is need to meet the needs of the students. I would modify my teaching in the future by being conscious of how important time is and how essential planning is, because if I would have had the time I would have planned more creative and more interesting lessons. The evidence for my success was being able to hear and read the children responses to the questions about community helpers during read-alouds and KWL charts, and finally, the development of a book by each child. 23 Stella: Comparing 1st and Last Journals In comparison, my first and last CA journals had some differences. My first journal was more descriptive about teaching strategies. My last journals included children’s actions and reactions to the lessons. I also included, by the end, examples of children’s dialogue and of their work. 24 Results—Content Analysis Adapted practice to meet needs of children: “Working with Sandy forced me to reevaluate my approach to at risk students and therefore strengthen my teaching practices and beliefs. I hope I have provided Sandy with some of the tools and the confidence to continue to succeed not only in spelling, but also in other areas of her education.” 14/14 students cited similar examples. 25 Results—Content Analysis Accurately predicted how children would respond to an activity and adjusted instruction accordingly. 9/14 students could make predictions about their children’s behavior. Kagen (1990) finds that such predictions are important indicators of effective teaching. 26 Limitations and Future Research Reflective Thinking Scale: Any numbered scale of reflective thinking places complex critical and creative thinking on a linear scale, which cannot capture the breadth and depth of these non-linear behaviors. An alternate scale that will be used future studies is based on M.J.Bierman’s work, and has been has been validated with similar populations. (Schweiker-Marra, Holmes, & Pula, 2003). 27 Limitations and Future Research (Continued) Sample Size: This is the beginning of a longitudinal study. Approximately 30 students will be added in the second year of the program. Validity and Reliability: Several measures will be taken to strengthen the design: Establishing inter-rater reliability Triangulation of measures of participant, instructor and outside rater assessments of reflective thinking Interviews of a sampling of participants 28