Basics of Hemodynamic Monitoring

advertisement

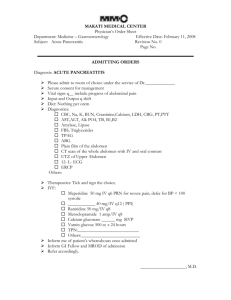

Case Based Presentation Severe Acute Pancreatitis, Or How I Spent My Christmas Vacation S. Mountain January 8, 2009 The Case The patient is a 25-year-old obese woman with a history of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) and hypercholesterolemia who presents to the emergency department for evaluation of the acute onset of abdominal pain. The patient describes the pain, which she says began 12 hours before her evaluation, as a constant epigastric cramping associated with nausea and vomiting. She denies fever, chills, change in bowel habits, or alteration in the character of her stool or urine. The patient's past medical history is significant for obesity, NIDDM, hypercholesterolemia, and depression. She is uncertain of the names of the oral hypoglycemic and antilipidemic drugs that had been prescribed to her. She does not use tobacco or alcohol. There has been no recent travel. Laboratory studies performed 3 months before her admission revealed an elevated cholesterol level of 597 mg/dL, with an HDL level of 42 mg/dL, and an elevated triglyceride level of 3034 mg/dL. The physical examination is significant for morbid obesity (weight, 301 lb); temperature, 37°C; blood pressure, 100/50; pulse, 110/min; respiratory rate, 16/min; regular heart rate; clear lungs on auscultation; and a diffusely tender abdomen without rebound or guarding. The stool is guaiac negative. Laboratory studies: – White blood cell count 11.6 x 103 – Hemoglobin 13.7 g/dL – Hematocrit 40.4% (normal: 37%-47%) – Sodium 135 mmol/L – Potassium 4 mmol/L – Chloride 101 mmol/L – Bicarbonate 11.2 mmol/L – Blood urea nitrogen 7 mg/dL – Creatinine 0.7 mg/dL – Calcium 7.3 mg/dL Laboratory studies: – – – – – – – – – – Glucose 219 mg/dL Albumin 2.6 g/dL Amylase 222 U/L Lipase 5562 U/L (normal: 25-300 U/L) Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 48 U/L Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 28 U/L Alkaline phosphatase 88 U/L Total bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL Cholesterol 784 mg/dL (normal: 190-260 mg/dL) Triglycerides 5250 mg/dL (normal: 10-160 mg/dL) Figure 1. The patient's serum, which is lipemic, is compared with normal serum. Figure 2. The abdominal CT scan reveals phlegmonous changes of the pancreas in the perirenal space, transverse mesocolon, and small bowel mesentery. 1. What is the diagnosis? Define severe acute pancreatitis (SAP). Todd Diagnosis: Pancreatitis (of the severe acute variety) – Evidenced by clinical syndrome, laboratory studies and imaging. Definition: Pancreatitis associated with other end organ failure, and/or complications . – – – – Necrosis Abscess Pseudocyst formation Radiographic: evidence of previous 3 complications, rather than degree of inflammatory changes. Severity of Illness scores (i.e. APACHE II > 8 2. What are the most common etiologies of SAP in developed countries? How about in North America (i.e. the USA)? What are some other causes of pancreatitis? What is the most likely cause in this patient? Noemie Acute Pancreatitis Annual incidence 4.9 to 35 per 100,000 Mortality of acute pancreatitis 10% and in severe AP up to 30% Two most common causes of AP are gallstones and alcohol (70%) Etiologies of severe acute pancreatitis Gallstones (35%) Alcohol (35%) Trauma Hypertriglyceridemia Drugs Infection Tumor Pancreas Divisum Post ERCP Hypercalcemia Idiopathic (10%) Autoimmune (PAN, SLE) Gallstone pancreatitis Most common cause in most areas of the world Only 3% to 7% of pts with gallstones dvp pancreatitis More common in women vs men Dx: – Ultrasound – ALT > 3 x normal has a 95% PPV1 – Bili and ALP does not influence dx 30 to 50% recurrence rate without definitive therapy 1. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994 Oct;89(10):1863-6. Acute Alcoholic Pancreatitis Most common dx in US ETOH might the production of digestive and lysosomal enzymes Can present as acute on chronic pancreatitis calcifications on CT Lipase:amylase ratio > 2 – 91% sensitivity and 76% specificity What is the most likely cause in this patient? chol 15.44, HDL 1.09, trig 34.27 Hypertriglyceridemia – Accounts for 1 to 4% of Acute Pancreatitis – Trig > 11 mmol/L can precipitate attacks – Acquired causes in adults: Alcohol, Obesity, DM, Hypothyroidism, pregnancy, Steroid, BBB, nephrotic syndrom – Trig > 11mmol/L opalescent and milky serum – Amylase may be falsely low – Goal is to lower their Trig<2.2mmol/L 3. What is the pathogenesis of SAP? Neil Pathogenesis Premature intrapancreatic activation of digestive enzymes – Autodigestion of pancreatic structure – Ischemia Inflammatory response – Cytokine release (IL-6, TNF-alpha, IL-1B) – Neutrophils – Platelet Activating Factor (PAF) Pathogenesis (2) Increased vascular permeability and microcirculation impairment – Constriction of arterioles and stasis of neuts – Ischemia results in rupture of lysosomes and release of cytokines – Increased vascular permeability and NO release Infection and necrosis 4. How is pancreatitis diagnosed? What are the roles and timing of amylase and lipase elevation, and how do they differ depending on the underlying etiology? What is the appropriate role and timing of imaging? Marios Diagnosing pancreatitis Diagnosis is usually made on the basis of: – Clinical presentation – Elevated pancreatic enzymes – Radiologic evidence of inflammation Pancreatic enzymes Most common and available are serum amylase and lipase Both are released into the circulation as their production continues in the face of reduced or absent secretion Levels do not correlate with severity Serum Amylase Rises within 6-12 hours of onset Elevated for 3 to 5 days in uncomplicated attacks May be lower in cases of hypertriglyceridemia-associated pancreatitis or in chronic alcoholics Serum Amylase Not specific to pancreatic disease: – Also produced by salivary glands and fallopian tubes – Can be absorbed from the gut in intestinal inflammation/infarction or from the peritoneum in cases of perforated bowel – Clearance is reduced in renal failure or with macroamylasemia (eg from pentaspan) Serum Lipase Thought to be more specific than amylase Can also be elevated in renal failure and in intestinal inflammation Appears earlier and stays elevated longer than serum amylase Lipase VS Amylase ROC curves for amylase and lipase Enzyme levels over time (actual figures from the paper) Role and timing of imaging in pancreatitis Abdominal series Usually part of the initial work-up in ER Can be normal, or show non-specific findings such as an ileus and air-fluid levels More specific findings include the coloncut-off sign, and a sentinel loop Colon Cutoff sign Colon Cutoff Sign Ultrasonography No role in the diagnosis or staging of severe pancreatitis – Bowel gas often obscures view of pancreas – Cannot identify necrosis Should be performed in all patients with first attacks of pancreatitis to rule-out gallstones Contrast-enhanced CT Unless there is diagnostic uncertainty, admission CTs are not usually necessary. Can be performed after 48-72 hours of conservative management if there is lack of improvement or worsening of clinical status. Intravenous contrast is preferred in order to show areas of necrosis, which will appear as unenhanced areas (< 50 HU) 5. What are some of the prognostic scoring systems used to predict severity of pancreatitis? Please discuss both clinical and radiographic scoring systems, but focus on those that are clinically relevant and useful for an intensivist. Naisan Clinical Scoring Systems Scoring systems Despite traditional measures, including scoring systems, serum measurements and radiological evaluation, acute pancreatitis patients remain challenging to risk stratify Serum lipase and amylase levels are poorly correlated with disease severity CRP is a good discriminator between severe and mild disease 48 h after the onset of symptoms. A cut-off level of 150 mg/l is accepted a BMI above 30, is a reliable predictor of severe outcome independently of age Lab Markers Predicting Severity In a meta-analysis of 399 patients presenting with acute pancreatitis, a serum haematocrit above 44mg/dl, BMI above 30 kg/m2, and pleural effusion on chest X-ray, were the most sensitive predictors of overall severity in acute pancreatitis. In the same paper, these criteria were validated in a prospective cohort of 238 American patients, as the ‘panc 3 score’ Brown A, James-Stevenson T, Dyson T, et al. The panc 3 score: a rapid and accurate test for predicting severity on Clinical Scoring Ranson Criteria distinguish between mild and severe pancreatitis with about 80% accuracy. The Ranson criteria, however, require evaluation of 11 parameters over 48 hours. The APACHE II scale has advantages in that it can be performed on admission, can be reevaluated at any time during the patient’s hospitalizaton. It is cumbersome to use clinically though MPM II Lemeshow S et al. Mortality probability models (MPM II) based on an international cohort of intensive care patients. JAMA 1993;270:2478-86 Severe Pancreatitis Severe acute pancreatitis is diagnosed if 3 or more of Ranson’s criteria are present, if the APACHE II score is 8 or more, or if one or more of the following are present: shock, renal insufficiency, and pulmonary insufficiency – Banks PA. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:377-86. Practical approach to predicting severity requiring admission to an ICU: a BMI above 30, and left-sided or bilateral effusion on CXR within 24 h of admission, An APACHE II score of at least 8 at 24 h after admission, and a CRP above 150 mg/l or a Ranson score above 3 at 48 h after admission. The development of organ failure or pancreatic necrosis (i.e., SAP by definition) also warrants immediate transfer to an ICU. – A. Wilmer / European Journal of Internal Medicine 15 (2004) 274–280 Imaging Criteria CT Severity Index --74-year-old man with acute pancreatitis Mortele, K. J. et al. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004;183:1261-1265 Copyright © 2006 by the American Roentgen Ray Society Radiological Scoring Gurleyik et al found a sensitivity of 85% and a specificity of 98% in predicting severe pancreatitis based solely on CT severity index. – Computed tomography severity index, APACHE II score, serumCRP concentration for predicting the severity of acute pancreatitis. JOP 2005; 6(6):562–7. severity index less than 3 had a 4% morbidity rate and no mortality, whereas patients who had a SI of more than 6 had a 92% morbidity rate and a 17% mortality – Balthazar EJ, Robinson DL, Megibow AJ, et al. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT in establishing prognosis. Radiology 1990;174(2):331–6. CT severity index patients who had a CT severity index greater than 5 were eight times more likely to die, 17 times more likely to have a prolonged hospital course, and 10 times more likely to require necrosectomy than patients who had a severity index less than 5 6. What is the appropriate initial management approach for a patient with SAP? Yoan Non ICU pt – NPO,Fluids – Analgesia, – No ATBx – Abdo U/S: R/O gallstone – Feed low fat when anorexia gone Management, ICU patient Shock, pulmonary failure, renal failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, multiorgan system failure Initially NPO Aggressive fluid resuscitation and monitoring (up to 500cc/hr + bolus) ATBX – Give if infected pancreatic necrosis (CT guided aspiration) – Do not give for fever only (inflammatory) Abdo U/S: R/O gallstone-ERCP if gallstone pancreatitis-Cholecystect in same hospit NJ feeds initiated early (after initial ressuc- possibly NG) TPN = 2nd line if feeds not tolerated CT C+: early if doubt and for baseline, then at 2-5d, then PRN vs q1week 7. When should the patient with SAP be monitored in an ICU or step-down unit? Todd Indications for ICU/stepdown admission: Shock (hypovolemic/distributive in setting of SIRS) – Need for invasive cardiovascular monitoring. – Hemodynamic support (pressors). – Massive volume resuscitation, usually “too heavy” for standard ward care, with resuscitation taking too long for typical busy ER. Organ failure – Lung injury – Renal failure Specific patient characteristics: elderly, morbid obesity (BMI > 30), extensive pancreatic necrosis (>30%) The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and was treated with intravenous fluids, narcotic analgesia, and insulin for her diabetes. Twenty-four hours after admission, the patient was noted to be tachypneic and dyspneic, requiring oxygen administration. 8. What is the frequency of lung injury in SAP? What is the proposed mechanism? Discuss the main preventive and therapeutic strategies. Noemie Lung injury and Acute Pancreatitis 30% of pts with acute pancreatitis dvp ALI/ARDS Responsible for 60% of all deaths in 1st week Mechanism: – Autodigestion of pancreas --> extravasation of proteolytic enzymes and vasoactive mediators – Systemic activation of inflammatory cells (Neutrophils) – Endothelial hyperpermeability and leak Current Opinion in Critical Care 2002,8:158-163 Lung injury and Acute Pancreatitis Prevention and treatment: – Low tidal volume ventilation – Inhibition of proinflammatory cascade Experimental/Animal models Antibodies against neutrophil chemoattractants Hypertonic saline – Attenuates neutrophil activation – Nutrition Enteral feeding shown to have better outcome (ICAM) Current Opinion in Critical Care 2002,8:158-163 Forty-eight hours after admission, the patient was found to have marked hypocalcemia (calcium, 0.7 mmol/L) and hypophosphatemia (phosphorus, 0.52 mmol/L), requiring supplementation. On rounds, you need to make a decision on nutrition, as the patient has not yet been fed. 9. What is the etiology of the hypocalcemia and hypophosphatemia? Neil What is the etiology of the hypocalcemia and hypophosphatemia? PTH – Suppressed secretion – Inactivitated Cytokines result in intracellular shift of phosphate 10. What is the optimal mode and timing of nutritional support for the patient with SAP? Are there any specific nutritional supplements that are beneficial in SAP? Are probiotics useful? Marios Nutrition in pancreatitis What is the optimal mode and timing of nutritional support for the patient with SAP? Total infectious complications Mortality Nutritional supplements in SAP Are probiotics useful? www.thelancet.com Vol 371 February 23, 2008 On the seventh hospital day, the patient develops a leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 13.35 x 103) with 32% bands. Panculturing is performed. You are concerned about the possibility of a secondary pancreatic infection. 11. What is the frequency of infectious complication in SAP? What is the impact on prognosis? Naisan Incidence 20% of patients develop pancreatic necrosis 15-50% pts that have pancreatic necrosis develop infected necrosis from translocation of gut-derived micro-organisms The highest risk group is those with 30% or more necrosis infection might occur within the 1st week, but its incidence tends to peak in the third week Prognosis death occurs in 10 to 20% of patients with infected necrosis. Infectious complications account for 80% of deaths from SAP, as well as the majority of late complications 12. Should patients with SAP receive prophylactic antibiotics? What is the evidence? What about selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD)? Yoan Question 12 Should patients with SAP receive prophylactic antibiotics? What is the evidence? What about selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD)? Yoan Nathens et al. Management of the critically ill patient with severe acute pancreatitis. CCM 2004 Cochrane Data Review/Metaanalysis 2006 Meta Analysis on ATBX in SAP Am J Gastroenterol 2008 US RCT Multicentric 100pts Proved Pancreatic necrosis Meropenem/placebo No decrease in Ix No change in hard outcomes Dellinger EP, Tellado JM, Soto NE, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Ann Surg 2007; 245:674–683. We recommend against the routine use of prophylactic systemic antibacterial or antifungal agents in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis in light of inconclusive evidence and divided expert opinion Nathens et al. Management of the critically ill patient with severe acute pancreatitis. CCM 2004 We recommend against the routine use of selective decontamination of the digestive tract in the management of necrotizing pancreatitis. Further investigation of this promising strategy in SAP is warranted Nathens et al. Management of the critically ill patient with severe acute pancreatitis. CCM 2004 Cultures all come back negative, and the empiric antibiotic therapy you initiated is discontinued. A repeat abdominal CT scan reveals worsening phlegmonous changes of the pancreas. The WBC continues to rise, as do the lipase and amylase. 13. What are the indications for surgery in acute pancreatitis and what is the optimal timing for intervention? What are the roles for less invasive approaches, including percutaneous drainage and laparoscopy? Are there any specific approaches that need to be considered with this etiology? Todd Indications for Surgery in SAP: Cholecystectomy (stone-associated disease) Necrosectomy: – Infected necrotic tissue (up to 40% of patients with SAP). – Possibly in sterile necrotic pancreatitis, in setting of recalcitrant SIRS/clinical deterioration, or failed attempts at enteral refeeding after 2-4 weeks. – Abdominal compartment syndrome in setting of pancreatitis. Timing Key is allowing necrotic pancreas to demarcate – Early in abdominal compartment syndrome, possibly in gallstone-related disease with cholecystitis. – Delayed, i.e. >2 weeks, for necrosectomy (barring uncontrolled SIRS), cholecystectomy. Other tools Less invasive options: – Percutaneous drainage (also useful for obtaining gram stain/culture to guide surgical decision and antimicrobial choice). May add continuous peritoneal lavage (no planned re-laparotomy) – Percutaneous necrosectomy. – Laparoscopy/Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD). Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography To decompress ducts and drain infected biliary sludge in patients with choledocholithiasis. – This is an early intervention (< 72 hrs) in setting of obstructive jaundice or biliary sepsis. Miscellaneous Plasma Exchange (PLEX) If lipemic plasma is the problem, get rid of it (at least temporarily)… Described in Therapeutic Apheresis 2002 Dec. 6 (6) 454-58. – 2 patients in Japan with necrotizing pancreatitis in setting of hypertriglyceridemia. Early PLEX--> survival after 60-day hospital course Delayed (20 days after onset of illness) --> death from multiorgan failure and sepsis. 14. Under what circumstances should patients with gallstone pancreatitis undergo interventions for clearance of the bile duct? Noemie Gallstone AP and interventions for clearance of the bile duct? CBD stones cause 35-40% of SAP 1998 UK guidelines: – In SAP with u/s proven stone with obstructive jaundice, urgent ERCP+ES is recommended – In mild suspected gallstone pancreatitis, conservative management is recommended. If pt’s condition fails to improve in 24-48H, ERCP is indicated European Journal of Internal Medicine 2004;15:274-280 Studies compared emergency ERCP+ES vs conservative Tx ERCP+ES significantly reduced overall complication rate (41% vs 31%) Trend toward mortality benefit Does not influence the course of mild biliary AP Ann Surg 2006;243: 154-168. Primary Cholecystectomy vs early ERCP One level I trial comparing ERC+ES vs cholecystectomy for mild biliary AP – Hospital stay and overall cost for cholecystectomy group Three level I trials looking at symptomatic CBD stones – suggested less recurrent biliary sx – Late mortality in ERC group was in one trial Recommend that mild biliary AP be treated with cholecystectomy + intraop cholangio. Ann Surg 2006;243: 154-168. 15. Is there a role for therapy targeting the inflammatory response in patients with SAP? Neil Is there a role for therapy targeting the inflammatory response in patients with SAP? Octreotide – Benefit in meta-analysis – Big RCT = no benefit Antioxidants vs placebo in SAP – no difference in organ function Lexipafant (PAF antagonist) – No improvement in DBRCT Siriwardena et al. The patient's abdominal pain and laboratory values stabilize and improve slightly with medical management, and surgical intervention is withheld. However, on day 11, the patient’s hemoglobin drops to 85 from 110 the day before. 16. List at least 4 potential causes of GI bleeding in SAP. Which are most common; which are least? Yoan Jury et al. Review Surg Tx Pancreatitis. MedClinNAm 2008 Cappel et al. Review Pancreatitis MedClinNAm 2008 Left colic artery pseudoaneurysm from pancreatitis presenting as upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Marichal DA, Savage C, Meler JD, Kirsch D, Rees CR. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009 Jan;20(1):133-6. Epub 2008 Nov 22. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis complicated with pancreatic pseudoaneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery: A case report. He Q, Liu YQ, Liu Y, Guan YS. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Apr 28;14(16):2612-4 During the remainder of her hospitalization, the patient's abdominal pain and laboratory values continue to improve. She recovers with conservative medical management and does not require surgical intervention.On hospital day 20, the patient is discharged in good condition. She is followed by her primary care physician and is compliant with gemfibrozil therapy and continues without reported recurrent episodes of pancreatitis for more than 1 year.