Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O'Brien, 2e.

advertisement

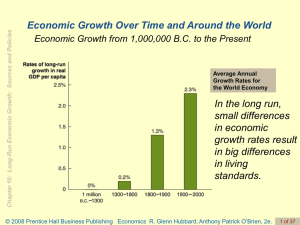

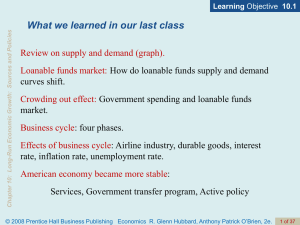

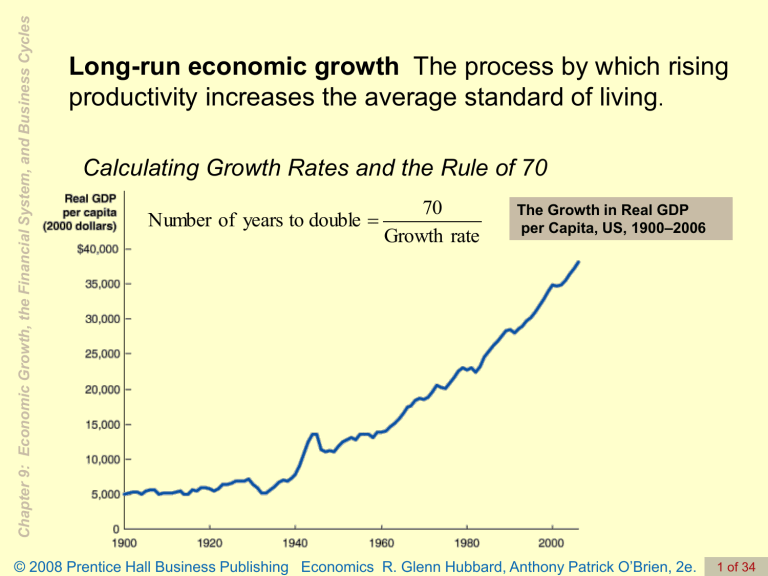

Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Long-run economic growth The process by which rising productivity increases the average standard of living. Calculating Growth Rates and the Rule of 70 Number of years to double 70 Growth rate The Growth in Real GDP per Capita, US, 1900–2006 © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 1 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Making the Connection The Connection between Economic Prosperity and Health © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 2 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Long-Run Economic Growth What Determines the Rate of Long-Run Growth? Labor productivity The quantity of goods and services that can be produced by one worker or by one hour of work. Increases in Capital per Hour Worked Capital Manufactured goods that are used to produce other goods and services. Technological Change Economic growth depends more on technological change than on increases in capital per hour worked. Technological change is an increase in the quantity of output firms can produce using a given quantity of inputs. © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 3 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles The Role of Technological Change in Growth Between 1960 and 1995, real GDP per capita in Singapore grew at an average annual rate of 6.2 percent. This very rapid growth rate results in the level of real GDP per capita doubling about every 11.5 years. In 1995, Alywn Young of the University of Chicago published an article in which he argued that Singapore’s growth depended more on increases in capital per hour worked, increases in the labor force participation rate, and the transfer of workers from agricultural to nonagricultural jobs than on technological change. If Young’s analysis was correct, predict what was likely to happen to Singapore’s growth rate in the years after 1995. © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 4 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Making the Connection What Explains Rapid Economic Growth in Botswana? © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 5 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Learning Objective 9.1 Long-Run Economic Growth Potential Real GDP FIGURE 9.2 Actual and Potential Real GDP © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 6 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Saving, Investment, and the Financial System Channeling resources to productive uses Financial system The system of financial markets and financial intermediaries through which firms acquire funds from households. An Overview of the Financial System Financial markets Markets where financial securities, such as stocks and bonds, are bought and sold. Financial intermediaries Firms, such as banks, mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies, that borrow funds from savers and lend them to borrowers. © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 7 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Saving, Investment, and the Financial System The Macroeconomics of Saving and Investment Y = C + I + G + NX I = Y − C − G - NX Sprivate = Y + TR − C − T = Y - (T -TR) - C T - TR = Net taxes Spublic= (T − TR) − G © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 8 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Saving, Investment, and the Financial System The Macroeconomics of Saving and Investment S = Sprivate + Spublic or S = (Y − (T - TR) − C) + ((T − TR) − G) or S = Y − C − G = I + NX So, we can conclude that total saving must equal total investment: I = S - NX - NX = Capital Inflows © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 9 of 34 The Market for Loanable Funds Demand and Supply in the Loanable Funds Market The Market for Loanable Funds Real interest rate Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Saving, Investment, and the Financial System © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 10 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Saving, Investment, and the Financial System The Market for Loanable Funds Explaining Movements in Saving, Investment, and Interest Rates An Increase in the Demand for Loanable Funds © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 11 of 34 Chapter 9: Economic Growth, the Financial System, and Business Cycles Saving, Investment, and the Financial System The Market for Loanable Funds Explaining Movements in Saving, Investment, and Interest Rates The Effect of a Budget Deficit on the Market for Loanable Funds Crowding out A decline in private expenditures as a result of an increase in government purchases. © 2008 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Economics R. Glenn Hubbard, Anthony Patrick O’Brien, 2e. 12 of 34