Electronic Payment Systems Investment Thesis Visa Inc.

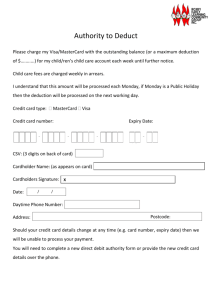

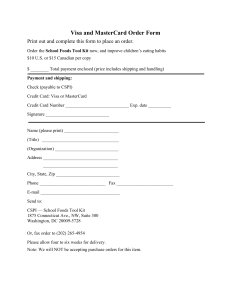

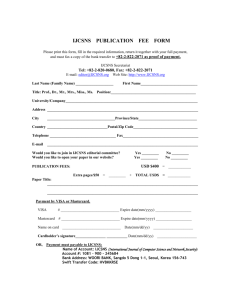

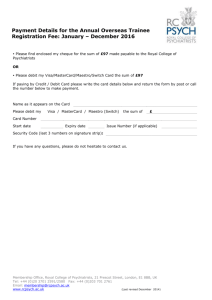

advertisement