int_cescr_ngo_aut_14625_e

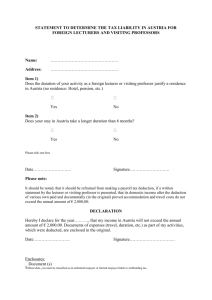

advertisement