Nuttall 1_Nov13_2010 (.doc)

advertisement

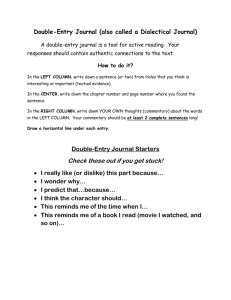

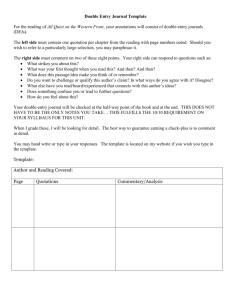

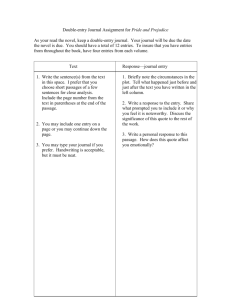

Page 1 of 8 Enhancing Students’ Critical Thinking through Effective Summary and Response Strategies Gabriella G. Nuttall Sacramento City College nuttalg@scc.losrios.edu http://web.scc.losrios.edu/nuttalg/ There are many different assignments that can help students practice their critical thinking skills. However, writing summaries and responses is one of the best tools to help students think more deeply about what they read. I generally follow these seven steps: 1. Identifying Key Words 2. Marking and Annotating a Text 3. Filling out a Summary Chart 4. Writing a Summary 5. Writing a Double-Entry Journal 6. Adding Quotations 7. Writing a Critical Response RESOURCES Kellogg, R.T. (2008). Training writing skills: A cognitive developmental perspective. Journal of writing research, 1(1), 1-26 Singh-Gupta, V., & Troutt-Ervin, E. (1997). Assessment of workplace writing and incorporation into curriculum. Journal of Vocational and Technical Education, 13(2). Retrieved from http://scholar.lib.vt.edu/ejournals/JVTE/v13n2/Singh.html Page 2 of 8 1. Identifying Key Words I use exercises similar to the following exercise to help students understand a writer’s attitude and tone by considering his/her language choices. We also look at signal words that help the students to identify the rhetorical mode(s) used in the text. Identifying Key Words and Signposts This passage classifies the two main types of language variation. Notice that key words that refer to main ideas are repeated throughout the passage. Signal words—or signposts—connect the paragraphs together and indicate the mode, or type, of text structure. VARIATION IN LANGUAGE (excerpted from Making Connections, by K.J. Pakenham, University of Michigan Press, 1998) NOTES It is possible to distinguish two main types of variation. The first of these, which can be called between-group variation, includes the sort of geographical or regional varieties mentioned in the preceding paragraph. A between-group variety refers to that version of a language that marks a person as belonging to a specific social group, e.g., as a native of New York City. Between- group varieties also include varieties associated with social class, with gender or sex, and with ethnic group. Other varieties, which have been less extensively studied, are those associated with age and occupation. Most people take it for granted that regional varieties, or dialects, exist in all languages. What might be surprising to some readers is that there are also distinctions between the English used by men and women. Research, however, has confirmed that such differences do exist. Researchers have found, for example, that in both British English and American English, men tend to use the nonstandard and informal pronunciation [-in] of the -ing ending more often than women do. Men also tend to use nonstandard grammatical forms (e.g., I didn’t see nothing instead of I didn’t see anything) more often than women. The second main type of linguistic variation can be labeled variation within the individual. This variation occurs within the English of one individual and is associated with factors that may change as the social situation changes. These factors include the different roles an individual might play (e.g., as a teacher, as a parent or child) and the relationships with the person or persons to whom the individual is speaking, (e.g., a close friend, a colleague, a subordinate, or a stranger). The individual’s English will also vary with the topic of the interaction (e.g., a topic related to a job or a topic related to the individual’s personal life) and with the physical setting where the interaction occurs (e.g., at a professional meeting, in a classroom, in a restaurant). Variation within the individual is also referred to as style-switching; in it, the speaker moves between levels of English that are perceived to be more formal or more informal. Page 3 of 8 2. Marking and Annotating the Text This task can be used to identify the author’s purpose, audience, main ideas, “signposts,” confusing points, etc. The focus will depend on the type of text and the lesson objectives. I usually select 2-3 areas that the students should identify. Sometimes we just focus on one, such as recognizing facts and opinions or a writer’s bias. Marking and Annotating To mark and annotate the text, do the following: Read the text again Underline more key words in addition to those we underlined in class Use these key words to help you identify important ideas Write notes in the margins about 1) main ideas 2) interesting details 3) confusing points or words Discuss your notes with a group of classmates. When you feel that you have a pretty good understanding of the reading, fill out the summary chart. Page 4 of 8 3. Filling out a Summary Chart This task helps students to approach the summarizing task in a systematic way, break down the text into smaller and more manageable chunks, begin writing the summary, put the ideas in the same order as the original source, and analyze the text structure and organization. Summary Chart As you fill out this chart, use some of the key words we have already identified in the text. Write the title of the reading and name of the author. What is the topic or issue discussed in the reading? What is the author’s main purpose? Is it to inform, persuade, entertain or explain? What is the main idea? Use your own words to summarize it. Write a one-two sentence summary of each paragraph. 1) 2) 3) How is the text organized? E.g., most important to least important ideas, comparison, etc. Page 5 of 8 4. Writing a Summary Synthesizing information is an important skill that the students will use often in their academic studies as well as the workplace. Summarizing teaches students to check for understanding, practice new vocabulary and key words, synthesize information and improve their overall writing skills. The task is simplified at this point because the students have already worked on steps that help them understand the reading. How to Write a Summary 1. Use the Summary Chart to write your summary. 2. Begin your summary by giving the title of the reading and the name of the author if available. 3. Leave out most details (examples, lengthy explanations, etc.). Your summary needs to be much shorter than the original article or passage. 4. Connect the sentences together. Use transition words when necessary. 5. Compare your summary to the original text to make sure that: a. The summary retells the same ideas found in the original text. b. It includes all the main points. c. It does not include your point of view. d. It gives the same importance to each idea as it is given in the original text. e. It includes some important key words and phrases from the original text, but most of the wording and the sentence structure are your own. f. It uses one or two author tags (“according to Smith” or “as Smith says”) to remind the reader that you are summarizing the author’s ideas, not your own. Page 6 of 8 5. Writing a Double-Entry Journal The next step after summarizing is responding to ideas from the text. A double-entry journal does not require students to integrate quotations and/or paraphrases into their own writing, so it is a more accessible task than a critical response. By writing a double-entry journal, the students can learn to: respond to important ideas in the text, make connections between new information and their prior knowledge, evaluate ideas through their own personal experience, and compare and contrast ideas from different texts. The Double-Entry Journal The purpose of a double-entry journal is to help you comprehend and comment upon your readings. It allows you to improve your comprehension while practicing your critical reading skills (analysis). Just by rereading your journal, you can tell if you focused too much on facts (left side full with little on the right), or if you have a good balance of facts and analysis. If you put some effort in writing your double-entry journals, you will be better prepared for more complex writing assignments and will be able to contribute thoughtfully to class discussions. 1. Divide a notebook page into two columns, making sure that the column on the right is wider than the one on the left. Use tables if you type your journal. 2. In the left column, write three or four quotations from the text. Write down the page number and paragraph number for each quotation. You should pick quotations that express important ideas or examples. If a quotation is too long (more than 3 lines), summarize it in your own words. 3. In the right column, write your analysis. Review the notes you wrote in the margins of the text and choose the comments you want to expand upon in your journal. These may include: questions about confusing parts or words (try to answer your own questions) definitions of key words comments about inconsistencies you may note in the text agreement with points presented by the author comparisons with other readings (notice differences as well as similarities) connections to your personal experiences and other real situations 4. When you finish writing your journal, read it again. If necessary, add new comments and/or questions. Page 7 of 8 6. Citing Sources (Quoting) The students have been learning how to paraphrase all along by writing summaries, but they do not yet know how to cite correctly. It is easier for students to learn this by using quotations rather than paraphrasing. Quoting can help students to: select salient points from the text, cite sources, use MLA, APA, etc., learn reporting verbs, learn introductory phrases, practice difficult sentence structures, and apply grammar knowledge. After giving the students a handout about quoting rules, the students practice in the computer lab where I can show the process of selecting and citing sources on a large screen. The following examples refer to readings from the textbook Reader's Choice, 5th edition, by Sandra Silberstein, Mark A. Clarke, Barbara K. Dobson and published by University of Michigan Press. The students were given a quotation and had to add the authors, the title of the article and the correct punctuation. Quoting Practice The first time you mention an article: 1. According to Ron Zemke, Claire Raines and Bob Filipczak, authors of “The CrossGenerational Workplace,” “Understanding generational differences is critical to making them work for the organization and not against it” (322). 2. According to Ron Zemke, Claire Raines and Bob Filipczak (322), having a clear idea of “generational differences is critical to making them work for the organization and not against it.” 3. Ron Zemke, Claire Raines and Bob Filipczak, in the article “The Cross-Generational Workplace,” state that “Understanding generational differences is critical to making them work for the organization and not against it” (322). 4. The article, “The Cross-Generational Workplace,” by Ron Zemke, Claire Raines and Bob Filipczak (323) states, “It is important to keep in mind the dangers of stereotyping and overgeneralization.” The second time you quote or paraphrase from the same article (or third, fourth, etc.): 5. Zemke, Raines and Filipczak explain that “It is important to keep in mind the dangers of stereotyping and overgeneralization” (323). 6. The authors (323) emphasize the importance of keeping “in mind the dangers of stereotyping and overgeneralization.” Page 8 of 8 7. Writing a Critical Response Finally, it is time to pull it all together. By the time they write a critical response, the students have a good understanding of how to identify key points and analyze a text. In a response, the students have an opportunity to examine ideas, share opinions, and become part of a discourse community. Critical Response When you respond academically to a text, it is your job to show that you have understood the reading and have thought deeply and critically about the ideas presented in the text. Here are some steps that you should follow: 1. Review the notes you wrote in the margins of the text. 2. Begin with a short summary of the text in order to introduce the main ideas to the reader. 3. Write a two page response which evaluates some of the ideas from the reading. As you write, be sure to: Use in-text citations. Remember to follow the quoting and paraphrasing guidelines you learned in this course. Analyze the author’s ideas and explain your opinions clearly. Organize your response and use signposts when necessary to help the reader follow your reasoning. Revise and edit your writing carefully. 4. If you have trouble getting started, these questions may help: Has the author made his/her point clear? How? Do you agree or disagree with the author? Why? Has the author left out important information? What is it? Does the author use effective examples to support his/her points? What are they? Why are they effective or ineffective? How does this reading make me feel? Happy/amused/angry/sad? Why? Does the reading remind me of a similar experience I have had? Which one? Do I know someone who has had a similar experience? What happened? Does the text remind me of another selection I have read? How?