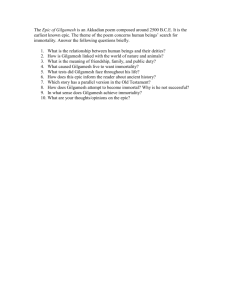

Gilgamesh

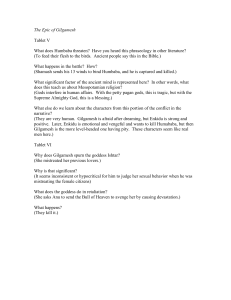

advertisement

The Epic of Gilgamesh (Volume A) History • Mesopotamia, 1900– 250 B.C.E. • Gilgamesh, priestking of Uruk • written in cuneiform • Ur • revised in Babylonian Ur Cuneiform • • • • wedge-shaped script 2100 B.C.E. clay tablets Sumerians Elements of Epic Writing • • • • • • • length content: historic, mythic motifs divine intervention heroic flaw orality and performance, writing language Binary Themes • • • • • • death and friendship nature and civilization power and violence travel and homecoming love and sexuality physical and intellectual journeys Death and Friendship Foil Dichotomies “Go up, Ur-Shanabi, pace out the walls of Uruk. Study the foundation terrace and examine the brickwork. Is not its masonry of kiln-fired brick? And did not seven masters lay its foundations?” (Tablet X, 151) Physical and Intellectual Journeys “Shall I not die too? Am I not like Enkidu?” (Tablet IX, 135) “For whom, Ur-Shanabi, have my hands been toiling? For whom has my heart’s blood been poured out? For myself I have obtained no benefit, I have done a good deed for a reptile!” (Tablet X, 150) Gods Women Flood Myths Discussion Questions Consider the etymology of the name “Gilgamesh” (“the old man is still a young man” OR “the offspring is a hero”). Is Gilgamesh’s name significant, despite the fact that he loses the plant that would return him to his youth? In what ways is it a fitting name despite his failure in the quest for immortality. How, in fact, has he actually accomplished immortality? Discussion Questions Throughout The Epic of Gilgamesh, many dreams occur, and often their meaning is unclear, or at least inscrutable for the characters who have them. Is there a general unity of the dreams? What is their purport? Do they come from the gods? Are they true? Are they good? This concludes the Lecture PowerPoint presentation for The Norton Anthology of World Literature Visit the StudySpace at: http://wwnorton.com/studyspace For more learning resources, please visit the StudySpace site for The Norton Anthology Of World Literature.