Laryngeal Dystonia

advertisement

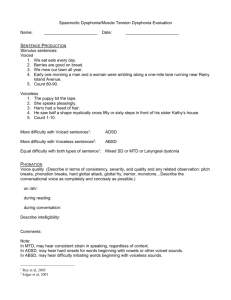

Spasmodic Dysphonia Evaluation and Management UTMB Department of Otolaryngology Olvia Revelo, MSIV Faculty Advisor:Michael Underbrink, MD Grand Rounds Presentation March 10, 2009 Overview Introduction Anatomy of the larynx Etiology Diagnosis Clinical features Therapy Pharmacologic Surgical Conclusion Introduction Spasmodic dysphonia (SD) Focal, adult-onset dystonia of laryngeal muscles Intermittent phonatory breaks during speech secondary to spasms Usually task specific - symptomatic when attempting voluntary speech May be asymptomatic during reflexive phonation (coughing, laughing, crying, yawning) Symptoms reduced/absent during singing or whisper Associations May be associated with: Other focal dystonias Underlying neurological Parkinson’s, ALS Environmental Blepharospasms, Torticollis, Writer’s Cramp Infection, trauma, meds Psychogenic stimulus Stress Demographics Affects approximately 1:10,000 Americans Female to male ratio 3:1 up to 8:1 Peak age of onset 35-45 Positive family history in 12% of affected pt’s Types of Laryngeal Dystonias Adductor – irregular hyperadduction of vocal folds with excessive glottic closure Abductor – incomplete, irregular vocal fold approximation Mixed – both elements are present Anatomy: Laryngeal Cartilage Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Cartilage Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Muscles Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Muscles Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Motion Abduction of vocal ligament Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Motion Adduction of vocal ligament Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Motion Tension of vocal ligament Netter Anatomy: Laryngeal Innervation Netter Etiology Currently unknown Historically psychogenic disorder Traube 1871 “nervous hoarseness” Current theory involves neurologic cause Basal ganglia involved in other focal dystonias Some patients have developed SD post head trauma Diagnosis Diagnosis is based on history and examination of the glottis during various laryngeal tasks. Aronson defined “idiopathic spastic dysphonia”: 1. The voice signs of SD 2. Absence of VC lesions/paralysis 3. Normal peripheral speech mechanisms 4. Resistance of symptoms to voice therapy and psychotherapy Clinical Features: Adductor Type Most common ~85% of diagnosed cases Choked, strained-strangled voice, with abrupt breaks in phonation in the middle of vowels Breaks are due to hyper-adduction of the folds Difficulty with “We eat eels every day” and “We mow our lawn all year” Clinical features: Abductor Type Rare ~15% of patients with SD Breathy, effortful voice with abrupt breaks resulting in whispered elements of their speech. Excessive and prolonged abduction during voiceless consonants (/h/,/s/,/f/,/p/,/t/,/k/) Difficulty with “The puppy bit the tape” and “When he comes home we’ll feed him” Mixed Type Extremely rare, with symptoms of both adductor and abductor type Diagnosis important for predicting treatment response Diagnosis Electromyography Fiberoptic laryngoscopy Videostroboscopy Aerodynamic testing Vocal spectrographic analysis Therapy Pharmacotherapy Botox Neuropharmacologic Voice Therapy Surgical Recurrent laryngeal nerve section Recurrent laryngeal nerve avulsion Therapy Surgical - Experimental Recurrent laryngeal nerve denervation and reinnervation Type II thyroplasty Posterior cricoarytenoid myoplasty with medialization thyroplasty Botulinum Toxin Goldstandard treatment for SD Prevents presynaptic release of acetylcholine (Ach) at neuromuscular junction. Different serotypes of botulinum toxin exhibit specific proteolysis of proteins involved in transport and binding of Ach vesicles to presynaptic membrane. Result in temporary paralysis Botox mechanism of action Release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction is mediated by the assembly of a synaptic fusion complex that allows the membrane of the synaptic vesicle containing acetylcholine to fuse with the neuronal cell membrane. The synaptic fusion complex is a set of SNARE proteins, which include synaptobrevin, SNAP-25, and syntaxin. After membrane fusion, acetylcholine is released into the synaptic cleft and then bound by receptors on the muscle cell. JAMA. 2001;285:1059-1070 Botox mechanism of action Botulinum toxin binds to the neuronal cell membrane at the nerve terminus and enters the neuron by endocytosis. The light chain of botulinum toxin cleaves specific sites on the SNARE proteins, preventing complete assembly of the synaptic fusion complex and thereby blocking acetylcholine release. Botulinum toxins types B, D, F, and G cleave synaptobrevin; types A, C, and E cleave SNAP-25; and type C cleaves syntaxin. Without acetylcholine release, the muscle is unable to contract. Botulinum Toxin Effects and Side Effects: Reduction in voice breaks reported by 48 hrs Treatment lasts an average of 3-4 months before recurrence of symptoms Most common side effect is breathiness Other side effects include: dysphagia, prologued voice loss, aspiration, hoarseness, pain at injection site and stridor (with PCA injection) Botulinum Toxin No absolute contraindications Used safely in children Give antireflux medication to patients with reflux 3 – 5% of patients have developed resistance to the toxin Resistant patients can sometimes be treated with other toxin serotypes Botulinum Toxin Injection technique for adductor SD (AdSD) Percutaneous injection guided by electromyographic (EMG) signals. Needle inserted through thyrocricoid membrane and directed upward toward contralateral thyroarytenoid m. Phonation and observation of interference pattern on EMG verifies position Thyroarytenoid injection for adductor spasmodic dysphonia. Needle is advanced through the cricothyroid membrane. Pitman MJ http://www.emedicine.com/ent/TOPIC349.HTM Botulinum Toxin Alternate injection techniques for AdSD All methods yield comparable results. Very patient and physician dependent Transoral laryngoscopic injections The transoral approach involved indirect visualization of the VF via standard laryngoscopicprecedure. VF anesthetized through application of topical cocaine sol’n. BTX is then injected along the superior margin of the VF Transnasal laryngoscopic injections . Transnasal technique uses a flexible nasolaryngoscope with a working channel that is equipped with a flexible catheter needle. Topical phenylephrine and lidocaine are sprayed transnasally, then the scope is introduced. Once in place, lidocainesol’n drip is applied to the surface of the VF via the working channel while the pt phonates to prevent airway penetration or aspiration. Then inject just lateral to the true VF (to avoid damage to VF mucosa) Transcartilaginous “point touch” injections Insertion of the needle through the surface of the thyroid cartilage halfway b/w thyroid Botulinum Toxin Injection technique for abductor SD (AbSD) Requires access to posterior cricoarytenoids Larynx is rotated manually away from injection site. Needle passed posterior to the posterior edge of thyroid at cricoid level into the PCA. Patient is asked to sniff to contract PCA and verify correct position Posterior cricoarytenoid (PCA) injection for abductor spasmodic dysphonia. Needle is advanced through the inferior constrictor muscle to the PCA muscle. Pitman MJ http://www.emedicine.com/ent/TOPIC349.HTM Botulinum Toxin Blitzer et al. 1999 Reported their 12 yr experience with more than 900 patients with SD 90% of patients with AdSD and 66.7% with AbSD achieved a normal voice after injection Injection after nerve section failure showed up to 81% improvement Patients with combined abnormalities only had 30% improvement -Level of evidence (LOE): A Botulinum Toxin Advantages Less invasive than surgery No permanent damage to nerve or laryngeal structures Temporary nature allows for dosage adjustments Readily available Disadvantages Need for repeated injections Unpredictable relationship between dosage and response Resistance to treatment Adverse side effects Pre-Botox Treatment Post-Botox Treatment Pre-Botox Treatment Post-Botox Treatment Neuropharmacology No controlled studies demonstrate effective symptom control Beta blockers – propranolol Anticholinergics – trihexyphenidylHCl (Artane) Benzodiazepines – diazepam, alprazolam Role has been to provide relief without any demonstrable symptom reduction Voice Therapy No demonstrated effectiveness in treating SD May help: Rule out psychogenic disorder Provide support for those who do not benefit from Botox (mild symptoms) Some patients use it in adjunct to Botox to prolong symptom free period Traditional voice therapy approaches for ADSD employ techniques for avoiding overpressure. Breathy voice onsets, reduced speech force, using a head focus, and laryngeal manipulation are aimed at reducing laryngeal tension. Can also use relaxation and respiration training to help gain insight and control of laryngeal tension during speech. Recurrent laryngeal nerve section Dedo 1976 Case series of 34 patients that had RLN section “All experienced symptom improvement” No objective measurement of outcome -LOE:C Dedo 1991 Retrospective review of 300 patients after RLN section 82% had little or no symptoms after 5-14 years No prospective comparative data available -LOE:B Recurrent laryngeal nerve section Aronson and DeSanto 1983 Followed 33 patients for 3 years post RLN section 36% maintained improved voices Of the 64% failed voices, 48% were worse than before surgery Effectiveness of unilateral RLN section for severe ADSD decreases with time Limitations: small sample study -LOE:C Recurrent laryngeal nerve avulsion Netterville 1991 Retrospective review of 12 patients No recurrence at 1.5 years -LOE:C Follow up report 1996 18 patients followed for 3-7 yrs post RLN avulsion 16/18 patients were without spasm Most common side effect was breathy voice – Six underwent medialization laryngoplasty -LOE:C Therapy Surgical Experimental Recurrent laryngeal nerve denervation and reinnervation Type II thyroplasty Posterior cricoarytenoidmyoplasty with medializationthyroplasty Recurrent laryngeal nerve denervation and reinnervation Berke and Blumin 2006 Retrospective study analyzing satisfaction surveys and perceptual evaluation of post operative voice 83 of 136 patients returned surveys with 91% satisfied with fluency of voice 46 patients provided voice recordings for perceptual evaluation: 26% had voice breaks, and 30% breathiness -LOE:B Recurrent laryngeal nerve denervation and reinnervation Limitations: high drop out rate (61%), small sample size, no long term prospective studies Advantages Permanent effect Less breathiness due to maintenance of VF tone from ansa cervicalis innervation Disadvantages Technical difficulty Recurrence of symptoms Does not prevent unwanted reinnervations Midline lateralization thyroplasty Isshiki et al. 2001 Retrospective review of 6 SD patients 5/6 patients obtained near normal voices Failure attributed to difficulty in lateralization and concurrent focal neck dystonia Limitations: small samples, no long term prospective studies, no objective measures described -LOE:C Atlas of Head & Neck Surgery—otolaryngology By Byron J. Bailey, Karen H. Calhoun, Norman Modified Type II Thyroplasty Midline lateralization thyroplasty (type 2 thyroplasty) after completion of the procedure. “A” type using a composite graft for the closure of a tiny perforation at or slightly above the anterior commissure. A muscle flap is used to cover the graft. G = A composite graft. Isshiki: Laryngoscope, Volume 111(4).April 2001.615-621 Modified Type II Thyroplasty B” type without using a graft. (A) The incised edges are pulled apart to test the lateralization effect on voice. (B) The incised edges are separated at a desired distance (usually 3–4 mm) and fixed with silicone shims. Isshiki: Laryngoscope, Volume 111(4).April 2001.615-621 Midline lateralization thyroplasty Chan 2004 Prospective case series with 13 subjects Used method described by Isshiki 9/13 patients failed; 2 had their surgery reversed Reason for failure unclear Limitations: small sample, only used self-rating assessments and no objective measures -LOE:C Unclear why some pts deteriorate over time, especially when they had good early results p sx. Presume that with time the VF hyperadduction is able to overcome the initial lateralization created by the shims because the underlying neuropathology has not been resolved. Continue to recommend BTX as gold standard. Midline lateralization thyroplasty Advantages: Optimal glottal closure can be adjusted and readjusted No damage of physiologic function Reversible Disadvantages: Technically difficult Shim displacement Does not relieve cause of SD Require careful patient selection Lacks reproducibility Limitations of a retrospective study Posterior cricoarytenoid myoplasty with medialization thyroplasty Shaw 2003 Case report of 3 patients with AbSD refractory to BTX treated with surgery and followed up to a year post surgery All reported improved subjective symptoms and showed objective reduction in phonatory breaks Limitations: Small sample and no long term prospective outcomes -LOE:D Posterior cricoarytenoid myoplasty with medialization thyroplasty Shaw , Ann OtolRhynolLaryngol (2003) 112:303-306 Summary Treatment Advantage Disadvantage Botulinum Toxin Type A (Botox) Current “gold standard”; Readily Not permanent cure; risk of available; less invasive immunoresistance; “breathy” voice Type B (Myobloc) Alternative for resistant patients Voice Therapy Inexpensive; No side effects; non- Not effective alone; requires invasive; no contraindications; high patient compliance; takes adjunct to BTX time to learn RLN Section / Avulsion “permanent” treatment Invasive; symptom recurrence Laryngeal adductor denervation-reinnervation “permanent” treatment; option for patients resistant to BTX Invasive; limited availability and long term outcome data Laryngeal framework approach “permanent” treatment; does not target nerve function, reversible Invasive; limited availability and long term outcome data PCA myoplasty with medializationthyroplasty “permanent” treatment; does not target nerve function Invasive; limited availability and long term outcome data Limited availability and use in SD Summary SD is an idiopathic d/o of the larynx. The mainstay of treatment continues to be BTX injections into the laryngeal muscles. BTX txt is not perfect -- there is an onset time characterized by a breathy voice and dusphagia and an offset time characterized by a recurrence of sxs. Occasionally pts can develop antibodies and resistance. Some pts don’t like to receive multiple injections a year. Because of these shortcomings alternative, more permanent treatments have been sought. Surgery for ASDS was initially developed in the 1970s but has been abandoned because of poor long term results. A RLN denervation and reinervation and laryngoplastic techniques may hold promise for long term treatment. All current therapies for SD are directed toward the symptoms of the d/o. There is still work toward understanding the underlying cause so we can then possibly develop a cure to the disease. References Pearson EJ and Sapienzam CM. Historical approaches to the treatment of Adductor-Type Spasmodic Dysphonia: Review and tutorial. NeuroRehabilitation (2003) 18:325-335 Sulica L. Contemporary management of spasmodic dysphonia. CurrOpinOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2004) 12:543-548 Berke GS and Blumin JH. Spasmodic dysphonia: therapeutic options. CurrOpinOtolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2000) 8:509-513 Grillone GA and Chan T. Laryngeal Dystonia. OtolaryngolClin N Am (2006) 39:87-100 Blitzer A, Brin MF, Stewart C. Botulinum toxin management of Spasmodic Dysphonia: 12-year experience in more than 900 patients. Laryngoscope (1998) 108(10):1431-1441 Mehta RP et al. Long-term therapy for spasmodic dysphonia-acoustic and aerodynamic outcomes. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg (2001) 127:393-399 Aronson AE and DeSanto LW. Adductor spastic dysphonia: three years after recurrent laryngeal nerve resection. Laryngoscope (1983) 93:1-8 Dedo HH and Behlau MS. Reccurent laryngeal nerve section for spastic dysphonia: 5 to 14 year preliminary results in the first 300 patients. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol (1991) 100:274-280 Dedo HH. Recurrent laryngeal nerve section for spastic dysphonia. Ann Otol (1976) 85:451459 Weed DT et al. Long term follow up of recurrent laryngeal nerve avulsion for the treatment of spastic dysphonia. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol (1996) 105:592-601 References Netterville JL et al. Recurrent laryngeal nerve avulsion for traemtent of spasmodic dysphonia. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol (1991) 100:10-14 Chhetri DK, Mendelsohn AH, Blumin JH, Berke GS. Long term follow up results of selective laryngeal adductor dennervation-reinnervation surgery for adductor spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope ( 2006) 116:635-642 Berke GS et al. Selective laryngeal adductor denervation-reinnervation: a new surgical treatment for adductor spasmodic dysphonia. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol (1999) 108:227- 232 Isshiki N et al. Midline lateralization thyroplasty for adductor spasmodic dysphonia. Ann OtolRhinolLaryngol (2000) 109:187-193 Isshiki N, Yamamoto I, Fukagai S Type 2 thyroplasty for spasmodic dysphonia fixation using a titanium bridge. ActaOtolaryngol (2004) 124:309-312 Isshiki N et al. Thyroplasty for adductor spasmodic dysphonia: further experience. Laryngoscope (2001) 111:615-621 Shaw GY, Sechtem PR, Rideout B. Posterior cricoarytenoidmyoplsty with medializationthyroplasty in the management of refractory abductor spasmodic dysphonia. Ann OtolRhynolLaryngol (2003) 112:303-306 Simonyan K et al. Focal white matter changes in spasmodic dysphonia: a combined diffusion tensor imaging and neuropathological study. Brain (2008) 131:447-459 Jurgens U. Neural pathways underlying vocal control. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews (2002) 26:235-258 References Stemple JC. Clinical Voice Pathology 3rd ed. Singular publishing grp(2000)119-127 SataloffRT. Treatment of Voice Disorders. (2005) Plural Publishing Inc. San Diego 167-177 StempleJC. Voice Therapy: Clinical Studies. Mosby-Year Book, Inc. (1993) 125-154 Fried MP. The Larynx: A Muiltidisciplinary Approach. 2nd Ed. (1996) Mosby-Year Book, Inc. 187-198. Cummings Shaefer SD. Neuropathology of spasmodic dysphonia. Laryngoscope (1983) 93:1183-1205 Rubin J, Satalof R, Korovin G. Diagnosis and Treatment of Voice Disorders. 3rd Ed. Plural Publishing Inc (2006) San Diego, CA