File

advertisement

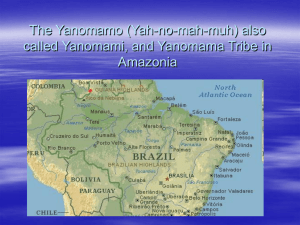

Ya̧ nomamö Cultural Anthropology Final Paper Cherina Santiago 12/5/2011 Ya̧ nomamo The Yanomamo also called Yanomami, and Yanomama are an Indian tribe who live deep in the jungles of the Amazon basin located between Venezuela and Brazil. The Yanomami tribe is widely believed to be the most primitive culture in the world today. These people are cataloged by anthropologists as Neo-Indians because of their cultural characteristics which have been in existence for more than 8,000 years. The Yanomamo population numbers approximately 33,000, the people live in scattered villages numbering around 125. Each village is essentially a large area called a shabono or yano. A shabono is a structure in a large circular shape with back walls and roofs made from trees and are thatched with palm leaves. The primary reason for this structure is a place for the Yanomamo to seek shelter from the rain as well as individual areas where people hang from their hammocks. Hammocks are attached to the roof and serve the purpose of a place to rest while socializing around a family fire. The Yanomamo are considered one of the most successful groups in the Amazon to achieve a superior balance with the environment. A good example of this balance is the way the forest space is used. The space is a systematic series of concentric circles. The circles are delimited so that usage has distinct modes and intensity. The first circle is a five kilometer radius and is for community use: female gathering, fishing, small-scale hunting, and agricultural activities. The second circle is a five to ten kilometer radius and is used for individual hunting and day-to-day food gathering for families. The third circle is a ten to twenty kilometer radius and is used for larger scale collective hunting expeditions lasting one to two weeks preceding a funeral, or three to six weeks for long multifamily hunting or gathering. When there is abundant game in the area, the Yanomamo camp in the third circle to gain a meat surplus, and may also cultivate and harvest crops. The Yanomamo society is based mostly on oral tradition. Tribe members are traditionally monolingual of their village dialect. The Yanomami language includes four subgroups which include Yanomae, Yanomami, Sanuma, and Yanam. Speakers of Yanomae are the largest linguistic subgroup in Brazil. Yanomami is the largest linguistic subgroup in Venezuela. In Yanomame the word Yanomami means man, people, or species. Many young Yanomamo men have learned Spanish and Portuguese, 1 however most only speak their native indigenous language. Education programs within the tribe have begun to focus on children learning their native language first and then can become bilingual, in an effort to enable members to communicate with outsiders. These outsiders include government officials, ranchers, colonists, and gold prospectors who may threaten the Yanomamo’s way of life. The Yanomamo is a hunter-gatherer society. However, they also perform some horticulturist subsistence strategies. The men hunt game or work in their gardens. Men mostly hunt monkey, deer, and armadillos. The women hunt frogs, crabs, termites, grubs, and gather wild fruits or mushrooms. Women typically gather with their young children. When needed, the Yanomamo grow banana, plantain, cassava, manioc, and corn. Tobacco is also cultivated and widely used by all members of the tribe. Fire sticks are used to make a fire; making fire with sticks is an arduous process and requires time, skill, and dexterity. A day’s supply of subsistence can be obtained on an average of two and a half hours. The Yanomamo’s settlement pattern is seminomadic containing micro-movements based on their subsistence needs and may move to more fertile land for farming, or macro-movements in response to threats. Since the roof of their dwellings is thatched, the humid rainforest climate causes rotting. When the roofs begin to rot, rodents infest the shabonos, so the tribe must move and build new villages or a new shabono at a nearby location. Gender roles exist and are relatively inflexible. Men hunt, build houses, and transport materials. Women clear land, work vegetable plots, and are homemakers. Women are also the primary child care takers. The Yanomamo art can most visibly been seen looking at their bodies. They wear no clothing. Mean wear strings around the waist and tie their foreskin to the string in order to keep their penis upright. Women wear a string around their back and between the breasts, and sometimes wear loincloths. The Yanomamo often paint their skin red using seeds from the annatto plant. Women and men both have the same straight round haircuts. Men typically wear multicolored bracelets made with bird feathers. Men also perforate their earlobes with cane and then decorate the cane with flowers or feathers. Sometimes they pierce their nose and lips with thin bamboo sticks. Women pierce their ears or lips using plant shoots decorated with flowers, palm shoots, or scented leaves and wear necklaces of beads and feathers. The Yanomamo women weave baskets using mamure fiber which are used for carrying loads. The baskets are red from crushed annatto and decorated with traditional designs and symbols in black, made from charcoal. The tools used for hunting, spears, quivers, and arrows, are also considered forms of art. 2 Yanomamo children are weaned when they are three. After weaning they are allowed to join the other children in the central yard to play. The children’s games mimic their parent’s activities. The boys hunt small game outside of the shabono, as well as play war using bows and arrows. The girls decorate each other with urucu, bake small manioc flatbreads, and assist their mother with tasks. Boys and girls both climb trees to obtain fruit and play games in the trees, such as pretending to be escaping from a jaguar. Children are rarely disciplined even though the Yanomamo have a fierce reputation. Infanticide is practiced by most Yanomamo villages. This occurs when a pregnancy is considered high risk or if pregnancy occurs soon after the birth of a previous child. Infanticide also takes place when a child is born either of an unwanted female or if the infant is deformed. The Yanomamo system of descent is patrilineal. Men exert power over women. Women are not considered in high regard, rape and sexual abuse are not uncommon. Lineage is not completely biological. It is believed that creating and developing a fetus requires multiple acts of insemination so there is a possibility of multiple biological fathers. All villagers descended from a common male ancestor have the same descent category. The common male ancestor may be defined as the mother’s primary husband in cases of unknown biological paternity. Yanomamo marriage can also be polygnous with one man commonly having multiple wives. Lineage groups are typically small and are limited because of frequent segmentation. This division usually occurs because of fighting between cousins over rights to women within their group. The extent of lineage seldom goes back more than three generations. Descent category is essential to determining if a person is an eligible spouse. When a male and female meet for the first time their first conversation is typically about their descent category. In the kinship system of the Yanomamo there are cross cousins and parallel cousins. A tribe member would consider his mother and all biological mothers’ sisters to be a mother and addresses them as such. Likewise the father consists of the biological father and his brothers. Parallel cousin marriage is rarely practiced to avoid an incestuous relationship. Women keep their patrilineal descent category when they are married. Women must marry outside of their descent category; that is a sibling or parallel cousin who would be called brother or sister. However, descent categories can become very complicated due to polygyny, polyandry, serial monogamy, age imbalance in generations, adoption, women captured in raids, redefinitions in relationships, and incestuous marriages that are not prevented. 3 Endogamy is a common marriage preference within a village. Marriage to cross-cousins is considered a very good match, especially if the parents live in the same village. This results in both spouses remaining in the same village. Marriages are almost always arranged and contribute to the survival and economical needs of the community. Another reason that endogamy is preferred is that it eases the burden on males to perform bride-service, during which the male must live with his parents-inlaw for several years. Bilateral cross cousin marriage generates a moiety system. Two intermarrying moieties dominate a village in numbers and status. When lineages segment they produce a new moiety structure. The Yanomamo are very focused on social structure. The first level of social status in their village is the localized patrilineal moiety. The second social relationship is the village. A village settlement has paired patrilineages which marry in the moiety pattern. Marriage alliances are the next social structure. Endogamy is mostly practiced but exogamy can happen as well to form military alliances with other groups. Feasting alliances are used to maintain a peaceful relationship with other villages when the groups are not linked by war or marriage. The groups will invite one another to elaborate feasts and gift giving from host to guest. These relationships will often turn into a marriage alliance or an enemy. Trading alliances are the last peaceful social relationship. Villages will trade specialized items with one another such as pottery to prevent hostilities. These groups do not have a cordial enough relationship to form marriage alliances or feast together. All groups that do not have an alliance with one another are considered enemies. These groups are in a constant state of war which usually results in the seizure of women. War can be a source for exogamous marriage. These social relationships can change frequently if alliances are unsatisfactory. A good example of the delicate balance of these relationships can be seen in the film, The Ax Fight. A group of visitors from Ironasi-teri were visiting family in the Mishimishimabowei-teri, but there were also members of the group who did not have a friendly relationship with the visitors. When a man from the Ironasi-teri refused to work in the host’s garden but demanded food, the woman tending the garden refused to feed him. The man then beat her with a stick and she went back to her family crying. Her brother and husband confronted the visitor. A fight broke out where several men fought with clubs, axes, and machetes. The fight continued until a man was knocked unconscious. An elder man then stepped in and people dispersed. However, the context of the fight can be interpreted differently because seeing the footage does not show all of the complex relationships between the two groups. 4 Yanomamo warfare takes place frequently. However, the reason for Yanomamo warfare is highly controversial. The publication of Napoleon A. Chagnon’s study Yanomamo: The Fierce People brought an implication that aggression is a human genetic attribute. It is said in Chagnon’s work that the tribe is engaged in endless wars over women, status, and revenge. In 1974 the anthropologist Marvin Harris offered the view that warfare was an adaptive response from a population stressed by limited food resources. Yanomami Warfare: A Political History, published in 1995, showed a connection between European presence and war. It seems that recent wars were fought over access to steel tools and other goods. Then, in the 2000 Patrick Tierney, a journalist, published Darkness in El Dorado: How Scientists and Journalists Devastated the Amazon. The book essentially blamed Chagnon for instigating war within the Yanomamo. In 1996, War before Civilization was released, written by Lawrence H. Keeley, an archaeologist who said that humans have always made war based on archeological cases of extreme violence. He said, “War is something like trade or exchange. It is something that all humans do.” In the article, On Yanomami Warfare: Rejoinder, Bruce Albert speaks on all aspects of previous writings. He theorizes that the Yanomamo warfare topic cannot be reduced to a by-product of reproductive, environmental, or contact-induced factors but rather that cultural framework must be looked at first to explain war within the tribe. He also believes that the warfare analysis cannot be complete without looking at the symbolic relationship between raiding and supernatural aggression. Accusations of sorcery are important in triggering cycles of intervillage raiding within the Yanomamo community. Therefore, culture must be the first source of information. Of all these theories Yanomamo warfare is still a debated topic. Religiously, the Yanomamo practice animism. They believe that the rainforest is not just animals or plants, but rather composed of animal spirits in every tree, flower, and shrub. The Yanomamo call these spirits xapiripë. They believe that in order to see these spirits the hallucinogenic drug called yãkõana or yopo must be taken. Yãkõana comes from drying and grinding bark of the virola tree. This process takes several days and is overseen by a shaman. Taking the drug is very painful and can cause extreme headaches and nausea. Yopo is inhaled by being forcibly blown into the nasal cavities by another person through a long pipe; this method represents a transfer of energy. Once the trance state is achieved the Yanomamo can communicate with the spirit world and relate to their visions through chanting and dancing. The act of taking the hallucinogen and communicating with the spirit world is a near daily practice. The shaman takes yopo so he can manipulate the spirits to maintain their presence inside his body, which provides him with spiritual power. The community shamans are healers as well 5 as protectors. The shaman initiation process is the transformation of that person into a higher being. The human body undergoes a metamorphosis to a cosmic body, what they call ‘corporeal cosmo-genesis’. A famous Yanomamo shaman, Davi Kopenawa explains the vision while using Yãkõana; ‘Only those who know the xapiripë can see them because the xapiripë are very small and bright like light. There are many, many xapiripë, thousands of xapiripë like stars. They are beautiful, and decorated with parrot feathers and painted with urucum (annatto) and others have oraikok, others have earrings and use black dye and they dance very beautifully and sing differently.’ The sounds that Davi are speaking of are based on a system called hea, in which each sound has its own unique meaning. For example an animal’s cry might mean that mangos are ripe or a bird’s song might mean that a woman has become pregnant. When a Yanomamo dies, the first reaction is anger since they do not believe that death is a natural phenomenon. It is thought that death is caused by an evil spirit, sent by a shaman of a hostile group. This belief often sparks holy wars among tribes. The Yanomamo funerary rites begin with weeping over the dead. The community then gathers around the deceased and adorns the body with feather, paint, and tobacco. The body is cremated, a week later the ritual called paushimou is held. This ritual is when the bones of the deceased are crushed and then consumed by relatives and allies. This practice is intended to keep the loved one with them forever. There is no inheritance within the Yanomamo. All property of the deceased is burned or forgotten. This property includes their name, body, and belongings. They believe that to keep any memory of the dead is gravely dangerous, as the person has gone onto another world, and no longer belongs in this world. Spiritual beliefs and practices are a core part of the Yanomamo culture. There are many threats to the Yanomamo people. Up until the 1960s, contact between the Yanomamo and the outside world was sporadic and limited. In the mid-1970s the Brazilian government started construction on the Northern Perimeter Highway which cut through the southeastern part of their territory. The Yanomamo population was decreased by nearly 20% because of new diseases brought to their land from workers, to which they had no immunity. These diseases included malaria, tuberculosis, and smallpox, one in five Yanomamo died. During the 1980s violence increased when close to 20,000 Brazilian gold miners invaded the tribe’s land. The Yanomamo fought back and even killed some of the miners, but lost nearly 4,000 of their people. In response, the Brazilian government made attempts to 6 protect Yanomamo communities. However, according to the American Anthropological Association, by 1990 only 30% of the original Yanomamo territory was protected from intruders. In the 1990s there were many murders committed by the miners and lumbermen due to land disputes. Researchers estimate that over 100 Yanomamo have been intentionally murdered since the discovery of oil on their lands. Currently there are as many as 3,000 gold miners working illegally on the Yanomamo’s land. These intruders carry disease which could severely damage the population of the tribe. There are also cattle ranchers who are deforesting the eastern borders of their land. Davi Kopenawa explains the dangerous consequences of mining, logging, and cattle ranching in the Amazon; they cut down trees and make holes, the dirt from the holes fills the river, the dangerous mercury they use kills the fish and animals, and the puddles from the holes attract mosquitos which spread malaria. In June of 2009, Davi went to Europe to ask that pressure be put on the Brazilian government to stop this invasion of land. He fears that the pollution created by this behavior will destroy the rainforests, and eventually the world. Of course, there is dispute over the Yanomamo’s beliefs in what the destruction of the Amazon would do to the planet. As shaman Davi attempts to convey their beliefs, he says, "The error of the whites is to take the riches of the land. You only want to take the riches. But the land is sacred. If the Yanomamai die the shamans will disappear and the governments will continue to take the land. You are worried about climate change. It is arriving. The rains come late, the sun behaves in a strange way. The world is ill. The lungs of the sky are polluted. We know it is happening. We are shamans. We care for the planet, the sun, the moon the darkness and the light. Everything that exists we look after. You cannot go on destroying nature. We will all die, burned and drowned, and that is the Yanomamai word." It is imperative that the Yanomamo continue to fight for their way of life because it could easily be lost in a global environment. The indigenous Yanomamo people aim to practice their culture now and in the future, the same way they have for thousands of years. 7 Bibliography Albert, B. (1990). On Yanomami Warfare: Rejoinder. Current Anthropology Vol. 31, No. 5, 558-563. Chagnon, N. A. (1983). Yanomamo: The Fierce People. New York City: CBS College Publishing. Davis, R. (2009, December). Making Waves Yanomami community under threat Davi Kopenawa. New Internationalist, pp. Issue 428, p36-36. Englebert, V. (2004). A Once Hidden People. World & I, Vol. 19, Issue 5. Ferguson, R. B. (2003, July-August). The birth of war: an archaeological survey concludes that warfare, despite its malignant hold on modern life, has not always been part of the human condition. Natural History Magazine. Gomez, G. G. (2007). Responsive research and community involvement among the Brazillian Yanomami. Proceedings of Conference on Language Documentation and Linguistic Theory (pp. 95-102). London: Peter K. Austin, Oliver Bond & David Nathan (eds) . Indian-Cultures.com. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://indian-cultures.com/Cultures/yanomamo.html John D. Early, J. F. (2000). The Xilixana Yanomami of the Amazon: history, social structure, and population dynamics. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Mustafa Khalili, M. T. (Director). (2009). Climate change is extremely dangerous for all of us: Shaman Davi Kopenawa [Motion Picture]. Scott Ennis, T. A. (1975). Film Guide for The Ax Fight . Documentary Educational Resources . Thomason, A. (1999, May 21). Yanomami. Retrieved from suite101.com: http://www.suite101.com/article.cfm/fourth_world/20044 Ushiñahua, C. (2008-2011). Yanomami Indians: The Fierce People? Retrieved from Amazon-Indians.org: http://www.amazon-indians.org/yanomami.html Vitiello, S. (2003, 09 18). Sounds of the Yanomami Tribe and Amazon Rainforest. All Things Considered NPR. (R. Siegel, Interviewer) 8