Apologizing to the harmed patient

advertisement

Apologizing to the harmed patient

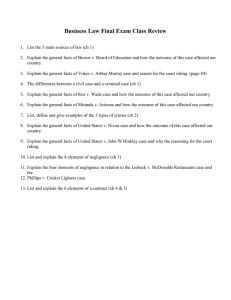

Dr. K Vij

Professor & Head,*

Dr. Anil Garg

Associate Professor,*

Dr. SS Sandhu

Professor,*

Dr. Rahul Khajuria

Demonstrator,*

*Department of Forensic Medicine, Gian Sagar Medical College, Banur, District Patiala, Punjab.

Correspondence E Mail: drvijk@yahoo.com

Abstract:

Section 44 of IPC defines ‘injury’ in its broadest sense. However, a medical injury/harm

carries some restrictive but intriguing concept. And, one of the most contentious and legally

complex areas is the difficulty in differentiating between errors arising from exercise of clinical

judgment and negligent behavior. Errors do occur. And, would occur as the adage “to err is

human” can’t be lost sight of. However, an equally reachable concept i.e. “to apologize is also

human” invites due consideration since it may benefit both parties (spiritually, psychologically,

and perhaps, legally).

Key Words: Apology, medical injury/harm, medical error/mistake, negligence, causation,

informed consent, communicating skills

Introduction:

Section 44 of Indian Penal Court (IPC) defines ‘injury’ as “any harm whatever illegally caused

to any person in body, mind, reputation or property”.1 A medical injury/harm may be

considered as : “any physical harm, bodily impairment, disfigurement, delay in recovery, or

death which (i) is more probably associated in whole or in part with medical intervention rather

than with the condition for which such intervention occurred, and is reasonably to be expected

as a consequence of such intervention, or (ii) is consistent with failure to provide timely and

appropriate intervention, or (iii) is the result of intervention to which the patient has not

consented.”2 In view of such an intriguing concept of medical injury and not losing sight of

much preached adage “to err is human”, it is not unexpected that we can altogether escape

committing errors and/or mistakes. Law Dictionary (Law Lexicon 2007) differentiates ‘error’

from ‘mistake’ thus: An ‘error’ is something incorrectly done through ignorance or inadvertence

whereas a ‘mistake’ is caused by bad judgement or a disregard of rule or principle. 3

Error in clinical judgement vis -a – vis negligent behavior:

It is understandable that one of the most contentious and legally complex areas is the

difficulty in differentiating between errors arising from exercise of clinical judgement and

negligent behavior. Undoubtedly, the leading case in this direction was that of Whitehouse Vs

Jordan and another (1981, 1ALLER 267) extending over the whole decade of the 1970s. 4Herein,

Mr. Jordan, an experienced obstetrician, was accused of causing cerebral palsy in an infant by

pulling too hard during a forceps delivery of a high risk pregnancy. The trial court found him

negligent and the plaintiff was awarded damages of 100000 £. However, the judgement was

reversed at the Appellate Court (by a majority of two to one) on the grounds that the issue was

a matter of clinical judgement not amounting to negligence. The plaintiff then appealed to the

House of Lords in 1981 wherein the five Law Lords, though ultimately upheld the majority

decision of the Court of Appeal; yet extended a dissenting note in respect of Lord Denning’s

distinction between an error of judgement and negligence. It was observed : “ while some

errors of clinical judgement were consistent with the due exercise of professional skill, other

acts or omissions in the course of exercising clinical judgement may be so glaringly below

proper standards as to make a finding of negligence inevitable”.4 The Supreme Court, too,

elucidated this aspect vividly in Spring Meadows Hospital and another Vs Harjot Ahluwalia and

another { 1998 (3 ) CPR I (SC), 1998 (1 ) CPJ I, and JT 1998 (2 ) SC 620} wherein the nurse gave

an intravenous injection of chloroquine instead of chloramphenicol to a child for the treatment

of enteric fever, leading to cardiac arrest and brain damage. The nurse plus the resident doctor

were held negligent. And, the hospital vicariously liable. The observations of the Apex Court, in

essence, were: “ Very often in a claim for compensation arising out of medical negligence a plea

is taken that it is a case of bonafide mistake which under certain circumstances may be

excusable, but a mistake tantamounting to negligence cannot be pardoned. In the former case,

a court can accept that ordinary human fallibility precludes the liability while in the latter, the

conduct of the defendant is considered to have gone beyond the bounds of what is expected of

the reasonable skill of a competent doctor”5

Evaluating the concept of ‘apology’:

Though we have been striving to reduce the rate of errors through system - based

practices and improvement in human skills, yet there is little doubt that the person – based

approach continues to hold sway and that the temptation to blame a particular individual is

hardly resisted by institutes / authorities. Admittedly, little attention has been paid to the

equally reachable concept i.e. “to apologize is also human”.6Putting it in some practical terms,

one may advocate that how can we characterize and address the human complexities of

unpleasant situations so that patients , families , and the doctors may reach some degree of

understanding and move towards forgiveness?.6Healthcare providers are often reluctant for

assuming personal responsibility and believe that they must “invent words with due care and

caution” or display a positive “spin”. Approximately 30 States in America have adopted “I am

sorry” laws, which to varying degrees extend shelter to doctors and render the comments

communicated to the harmed / injured patient inadmissible as evidence for proving liability. 6

Depending upon the wording , the legal effect/ affect of an apology can fall on a continuum

ranging from innocent expressions of sympathy to overt, supportive evidence of wrongdoing. In

Phinney Vs Vinson (605 A. 2d 849), the plaintiff argued that the apology expressed by the

defendant in itself was sufficient evidence of liability. But, the Supreme Court of Vermont

concluded that, probative though it is, an apology is not the automatic equivalent of legal

liability for wrongdoing.6 However, a contrary result was reached in Greenwood Vs Harris

{(1961, Okla.) 362 P. 2d 85} wherein the court held that it was not possible to interpret the

defendant’s statements other than an admission of the defendant’s failure to use and apply the

customary degree of skill exercised by physicians in the community.6

As obvious, examples are available to show that the courts have gone both

ways on this subject and have progressively been conveying that error , mistake , and a bad

result are predominantly medical concepts requiring evidence – based judgements,; whereas

fault , negligence, and culpability are legal concepts approached through legal standards which

necessitate taking into account other elements such as scope, standard of care in a given

scenario , and causation (showing a reasonably close and “causal connection” between the

negligent act or omission and a resulting injury/harm i.e. the so called legal or proximate

cause).And, therefore, efforts need be concentrated to find a balancing point between two

compelling impulses i.e. the compelling urge to say “I am sorry” on the one hand pitted against

the creeping danger of legal liability on the other since one never knows that how far a “sorry”

will be stretched . And, interpreted as legal weakness transforming an indecisive plaintiff into

an aggressive opponent who senses an easy victory.6This is especially so in the prevailing

societal shake-up wherein factors like right to information, quality assurance and

accountability, close involvement of patients in understanding their illnesses and making

decisions to accept or refuse treatment, etc; are increasingly heaping up.7

Conclusion:

Medical science is not a precise science, but rather a scientific humanism. It may be advocated

that ‘the apology’ should be a safe-worded work of art commensurating with the situation.

Errors do occur (and, probably, would occur).However, during these days of commercialism,

often the public has been raptorial for new sources of pecuniary advantage. And ungrateful

patients, at times, look - upon the field of medical negligence as a Land of Ophir8. Self –

policing combined with timely expression of sympathy and benevolence can go a long way in

unfolding pleasant results for both parties, spiritually as well as psychologically. And, perhaps,

legally too8. The attending doctor must convey his genuine concern about the unfortunate

event and express the same in comprehensible non-medical –terms preferably in the local

language. Doctors who are open-minded and communicative are much less likely to be

complained against as patients / attendants are often forgiving of errors committed by a

friendly and concerned medical professional. It has been forwarded that a high proportion of

complaints are precipitated or escalated into legal action by a progressive breakdown of the

doctor-patient communication.9 An illuminating example in this context may be cited through

the case entitled Nizam Institute of Medical Sciences Vs Prasanth S Dhananka & Others decided

by the Supreme Court on 14th May 2009 wherein the award of Rs . 15 Lac granted by the

National Commission, surprisingly enough, was enhanced to Rs. 1 crore by the SC . Herein, the

complainant (a student of IT engineering) was operated- upon for ‘neurofibroma’ (a benign

encapsulated tumor resulting from proliferation of Schwann cells….. a kind of nerves cells

named after the German histologist ) by a cardio-thoracic surgeon at National Institute of

Medical Sciences (NIMS). However, the complainant developed paraplegia with complete loss

of control over the lower limbs and some other related complications rendering him incapable

of all normal chores of life. The complainant and his parents approached the National

Commission alleging utter negligence on the part of the doctors and making NIMS vicariously

liable and the State of Andhra Pradesh statutorily liable. And, ultimately succeeded in having

such an exemplary amount of compensation primarily on two accounts : (i) Not associating a

neurosurgeon during the operation since the nature of the tumor fell under that field and (ii)

apathetic attitude of the attending doctors, especially the concerned surgeon (Not to talk of

discussing the things, they never heeded to repeated requests of complainant’s father for

supplying a detailed report as to the prognosis of his son’s condition so that he could discuss

the same with experts from some developed countries and adopt timely measures for better

quality of life of his son)10. Another related illustration may be sought in the case entitled

Samira Kohli Vs Dr. Prabha Manchanda and another (SC judgement dated 16.01.2008) wherein

it was categorically conveyed that “the ‘informed consent’ is a process extending over time

encompassing exchange of information, not a form once filled and got signed. The most

significant aspect is the necessity to convey to the patient doctor’s readiness to share the

information and be available to discuss anything the patient may fear as a risk, a side-effect, or

a concern about the proposed treatment”11. Medical profession can afford some eagerness in

expecting the proffered benefits of the solacing approach, though some disillusioned segment

may by nature be so timorous as to apprehend every path beset with lions.

References:

1. KD Gaur. Textbook on indian penal code 4th ed. 2009: universal law publications. p. 92

2. Chhuttani PN. A surgeon’s inquest. Tilok Tirath Vidyavati chhuttani charitable trust,

Chandigarh:1996.p 13-4.

3. P Ramanatha Aiyar: Law Lixan. 3rd ed. 2007: Wadhwa & company, Nagpur. p. 1634,3037

4. Polson CJ, Ghee DJ. The essentials of forensic medicine. 4th ed. 1985: Pergamon press:

UK. P. 756, 657.

5. Koley TK. Medical Negligence and the law in India. Oxford University Press, New Delhi:

p. 95-6.

6. Block AL. Disclosure of adverse outcome and apologizing the injured. chapter 28

patient.Legal medicine. 7th ed. 2007. American College of legal medicine. Mosby

elseveir. USA. P. 279 – 84.

7. Vij K. Textbook of forensic medicine. 5th ed. Elsevier India. 2011. p. 350

8. CG Tedeschi, William G Ekert, Luke G Tedeschi, forensic medicine, 1st ed. 1977, p 1216,

1223

9. Kumar N. Medical profession and consumer protection act. 2012 Bharat law house, New

Delhi: p. 704

10. Nizam institute of medical sciences Vs Prasanth dhananka Civil appeal no. 4119 of 1999

and 3126 of 2000, SC: 14-5-2009

11. Vij K. Textbook of forensic medicine. 5th ed. Elsevier India. 2011.p. 372.