The View from Inside Anti-Corruption Authorities (ACAs

advertisement

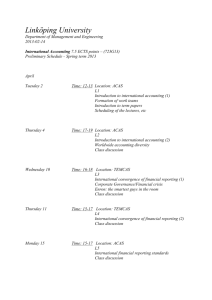

Francesca Recanatini Senior Economist The World Bank Prepared for the European Anti-Corruption Training Laxenburg, September 20, 2011 1. Brief history of ACAs in the World and in Europe 2. Challenges faced by ACAs 3. Structure and mandate of ACAs 4. Institutional structure and relation with other agencies 5. Resources and internal organization 6. Independence, oversight and accountability 7. External stakeholders and expectations 8. Lessons learnt and emerging issues Anti-Corruption Authority (ACA): a specialized agency, body, unit or department established by a government that has the mandate of addressing corruption 1980s and 1990s: establishment of international standards and agreements and parallel mushrooming of ACAs Anti-Corruption Authorities in our work Croatia Czech Case Studies: Rwanda, (2001) Republic Romania Indonesia, Jordan, Morocco, (1991) Slovakia Moldova Serbia (2002) Sierra Leone, Ethiopia, Slovenia (2004) (2002) (2010) Austria Hungary Korea, Mongolia, Slovenia, Latvia (2004) Estonia (2010) (1995) Tanzania Kosovo Montenegro (2002) Macedonia (1918) (2007) (2001) Mongolia (2002) Jordan (2007) (2008) Morocco UK Senegal (2007) Yemen (2003) Bhutan (2007) Sierra Leone (2006) Haiti Ethiopia (2000) (2004) Burkina Faso (2001) Kenya (2007) (2005) Rwanda Cameroon Mauritius (2003) (2006) Malawi (2002) (1997) (2007) Jamaica (1962) Guatemala (2008) Costa Rica Mexico (2004) (1999) Brazil (2001) Argentina (1999) Peru (2010) Barbados (1961) Uganda (1986) South Korea (2002) Philippines (1987) Singapore (1952) Indonesia (2004) Madagascar Hong Kong (2004) Sri Lanka (1974) Botswana (1994) Namibia Nepal Tanzania (1994) Mozambique (2006) (1992) (2007) Lesotho (2004) India Bangladesh Zambia (NA) Pakistan (1984) (1972) (1982) (1999) Anti-Corruption Authorities in Europe ACAs have been established in many European countries starting from mid-late 1990s. 24 of the EU member countries have ratified the UNCAC; excepting, Czech Republic, Germany and Ireland There is no single European model, but different approaches ranging from law enforcement, prevention, and multi-purpose anti-corruption bodies. Anti-Corruption Authorities in… Latvia 2003 Germany 1995 Norway 1989 Lithuania 2004 Ireland 1995 Poland 2006 Czech R. 1991 UK The Serious Fraud Office (SFO) 1987 Anti-corruption Unit (OACU) 2006 Portugal 2001 Spain 1995 Belgium 1998 France 1993 Italy 2004 Austria 2010 Ukraine 2004 Hungary Moldova 2004 2002 Romania Bulgaria 2002 2001 Macedonia 2002 Croatia 2001 Slovenia 2004 Montenegoro 2005 Slovakia Bosnia –H 2004 2002 Wide support of ACAs by multi/bilateral donors However, observed limited “impact” (Meagher (2005), Doig et al.(2005), Heilbrunn (2004), U4 (2007), UNDP (2005), Pope (1999), De Souza (2009), Council of Europe (2004)) GRECO reviews. 2010-2011: UNCAC review. Any lesson learnt? Council of Europe and GRECO Reviews Most countries in Europe have followed up on the requirements of the 20 Guiding Principles and the Criminal Law Convention on Corruption and established specialized anti-corruption services . Many ACA combine several functions. Public education and preventive functions have been neglected throughout Europe. Even ACAs that have a mandate in this field, public education and prevention remain marginal. Council of Europe and GRECO Reviews, cont. In some countries, ACAs have been sufficiently resourced to fulfill their functions; in many others, however, staff, financial and other means remain a challenge. The independence of anti-corruption services, in particular of those with law enforcement functions, remains a difficult issue. In many cases the precise role of anti-corruption services and their relationship to other institutions and actors may need to be defined more clearly. Can ACAs be (or become) an effective tool in the fight against corruption? If so, which factors or policies can be used to make ACAs more effective? => Starting point: a more systematic analysis of ACAs and of “factors” that can affect their functioning and effectiveness Initial information based on Workshop (March 2010) with 10 ACAs Factual information from 58 ACAs collected through a mailed-in survey. Plus 10 case studies (in-depth interviews in the field) Data Portal on ACAs forthcoming (launch planned for November 2011) On going work and data collection Need to have key institutions and laws in place jointly with support of the country leadership Politics and ACAs Tension between prevention and prosecution Trade-offs: the “big fishes” or small ones? Limited resources Perceived unfair evaluation of ACAs and their activities especially in the area of prevention Engaging the private sector ACAs can take many forms and display different functions and mandates, from prevention to investigation and prosecution, policy and research and outreach. Tension among practitioners when it comes to the functions that ACAs should have. Organizational theory recommends single mandate to increase effectiveness. But => “effective” ACAs among both single function agencies and multi-function agencies (Hong Kong, Brazil vs. Slovenia). Sierra Leone’s Anti-Corruption Commission (2000) Its mandate: prevent corruption and investigate allegations of corruption. No prosecutorial powers: all prosecutions were to be authorized by the Attorney General’s office before going to trial. Attempts to establish an independent Committee to review investigations and approve prosecution of cases were rejected as unconstitutional. Historical difficulty in securing convictions led to the revision of the mandate of the ACC through a new Anti-Corruption Act in 2008. The new Act grants prosecutorial powers to the ACC and establishes a prosecutorial unit for that purpose; it increases the number of corruption offenses; and establishes an Advisory Board on Corruption made up of representatives of civil society. In 2009 the ACC handled 122 investigations. 11 cases resulted in convictions and 10 in cautions; 9 cases are still pending trial; 24 were closed for lack of evidence; and the rest are ongoing. => Importance of creating an enabling institutional and procedural environment for anti-corruption efforts Clear mandate leads to better coordination among different agencies Need for clear agreements among agencies Important to understand who was performing some of the functions that the ACA is taking over and why it was not working Good examples of “links” with central banks, judicial agencies and revenue monitoring agencies Less common => relations with regulatory agencies and agencies at the local level Remaining challenge: de jure versus de facto The Supreme Audit Board (BPK) Provide the Investigative audit report, initial data, state loss estimation Financial Intelligence Unit (PPATK) Provide the Suspicious Transaction to support investigation process Bank and Insurance Companies Provide the Financial Statement to support investigation and asset tracing process Other Departments (National Land Agency, Immigration, Department of Law and Human Rights, etc) Provide supporting data related to the case (People Movement System, Company Profile, etc) UNCAC does not distinguish between federal and state (local) level anti-corruption efforts. The mandates and establishment of ACAs should be “in accordance with the fundamental principles of its legal system”. Decentralizing ACAs at the state and municipal level demands a coordination system among the different agencies. If the AC legislation/institution covers both federal and local level, it is essential to clarify the institutional arrangement in terms of mandates and coordination with state authorities. Plus, enough resources need to be available to have a central authority and many field offices. Critical to get the technical and organizational foundations established. But… …resources are a constraint. Potential factors : Lack of a long term horizon commitment Unskilled staff Donors’ involvement Strategy for coping with limited resources (ex. triage of allegations, focus on innovation and IT) Donor Involvement 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 Africa Europe East Asia Yes Latin America No South Asia Middle East and North Africa Importance of legislative set up Independence: selection/removal of ACA leadership and freedom of action Importance of legislative set up Independence: selection/removal of ACA leadership and freedom of action Reporting line Accountability: administrative and judicial Established mechanism to show results. 81 % of the 58 Surveyed ACAs measure the performance of their activities somehow. Does your agency measure performance? No 19% Yes 81% Does your agency measure performance? Prosuction Investigation Prevetion Yes No 0% 20% Prevetion 37 6 40% 60% Investigation 24 7 80% 100% Prosuction 20 32 The mandate of the ACAs included in the sample is - 86 % Prevention, - 77% Investigation and - 38% Prosecution. Mongolia: number of cases investigated and solved under the law, percentage of public officials who submitted income and asset disclosure forms, number of actions plans adopted by public organizations and local governments Indonesia: number of cases investigated and conviction rate Brazil: number of internal investigations completed and penalties enforced, number of companies suspended or debarred, data portals and number of visits, number of training delivered and of participants Importance of legislative set up Independence: selection/removal of ACA leadership and freedom of action Reporting line Accountability: administrative and judicial Need for a clear and established mechanism to show results. But… Political interference remains the key challenge 2004: a government’s change in Slovenia shifted the tide of political support away from the Commission for the Prevention of Corruption. February 2006: Parliament passed a new law that eliminated the need for a separate agency in favor of a commission composed of deputies from the National Assembly. The Commission organized a group of experts to prepare a counter proposal while lobbying 30 MPs to communicate the arguments to the Constitutional Court. April 2006: The Constitutional Court suspended the law as a temporary measure and later declared at least a quarter of the provisions unconstitutional. The Commission faced political pressure in 2008 and 2010, when the National Assembly demanded the resignation of its Director in two separate cases. In 2008, Parliament adopted a decision to remove the Director unless he provided proof of the Commission’s findings in a bribery case involving the Prime Minister and the previous government => not a lawfully valid reason for the Director’s removal from office. He was able to remain in office. In 2010, formal proceedings for the Director’s removal were initiated by the Parliamentary group serving as the oversight mechanism for the Commission, in response to the Commission’s refusal to provide confidential details about corruption cases, including the names of whistleblowers. The decision was postponed indefinitely when it became apparent that the majority required to carry the decision would not be achieved. In June 2010, this Parliamentary oversight group was abolished by virtue of the new Integrity and Corruption Prevention Act. Emerging Lessons: The existing legal framework paired with a strong internal leadership was essential to fence off the repeated political attempts to interfere with the Commission’s work. Critical: To manage expectations and to balance sensationalism with prevention work are key (SL, Nigeria, Kenya, Indonesia) Citizens and the media are powerful tools that can create an enabling environment. But… …the ACA needs: Continuous engagement with public and with the media for inputs and for feedback (KPK) To provide unrestricted access to information To have communication strategy to avoid risks linked to political pressure (Slovenia) • • The Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) has a mandate to prevent, investigate and prosecute corruption. Two critical factors: 1. KPK has achieved 100 % conviction rate in corruption prosecutions. It has in-house investigators, a staff of prosecutors (seconded from the Attorney General’s Office), and a dedicated Anti-Corruption Court presided over by ad hoc judges (selected and screened). Between 2003 and 2009 KPK successfully prosecuted over 150 senior officials: 68 percent received sentences of 2-5 years, 10 percent of 5-10 years, and less than 5 percent of more than 10 years. In contrast, Courts of General Jurisdiction in Indonesia have an almost 50 percent acquittal rate on (more minor) corruption cases brought by the Attorney General’s Office. Important factors that can help explain the KPK’s success: KPK investigators have the authority to gather evidence (wire-taps, bank accounts, tax statements); are trained in gathering evidence; and have the authority to make arrests and seize assets; Investigators and prosecutors work closely together, and the Commissioners review all cases to ensure only those with sufficient evidence to secure a conviction are taken to trial 2. Social media played a vital role in KPK’s political survival KPK’s Chairman was arrested on murder conspiracy charges, and two other Commissioners suspended and arrested on charges of corruption in 2009. The Chairman was convicted. The public felt that these charges, particularly the unrelated charges against the two Commissioners, were an attempt to undermine KPK. Popular support for the Commissioners was widespread and vocal. Public demonstrations were held, and a support page was launched on Facebook, attracting over a million members. A Presidential Commission was rapidly established to review the cases. The charges were eventually dropped after wire-tapped evidence was produced before the Constitutional Court that the allegations had been rigged. ACAs can have an impact. The challenge may be to be able to measure it. Factors that emerge as determinants of success: Strong political support from the country leadership as necessary but not a sufficient condition Middle management needs to work for change as well. Implementation of a comprehensive and clear legal framework for anti-corruption work. Effective mechanisms for inter-agency coordination. Adequacy of financial and human resources. Effective and continuous communication with citizens. Replication of “successful experiences” should be done only with caution, after having carefully understood and integrated country-specific factors Political pressure, vested interests and State Capture are the critical challenge Key to manage expectations and establish performance indicators (in order to capture the impact of ACAs activities), beyond the number of cases investigated and/or prosecuted. External assistance should be tailored and donors should work in partnership with ACAs to promote a mediumterm view, focused on building local capacity and promoting the sustainability of anti-corruption efforts. The Office of the Comptroller General (CGU) is the internal audit unit and the anti-corruption agency of the Brazilian Federal government. Main functions: Corruption Prevention and investigation (Administrative investigation only) CGU has launched several initiatives aimed at raising awareness and preventing corruption, including: 1. Public Spending Observatory (ODP) – was established in 2008. Data-matching and tracking system designed to detect fraud and corruption. ODP provides CGU and other government agencies information on the quantity and quality of public spending as well as with indications of sensitive areas of public spending in terms of corruption risk. 2. Transparency portals – information on resources applied by federal bodies, federal resources transferred to local governments and transactions on the federal government’s Payment card. 3. National Debarment List – list of firms currently debarred and temporarily suspended by the Government. 4. Education for ethics and citizenship – CGU launched an ethics and citizenship education program now included in the national school curriculum. 5. Eagle Eye on the Public Money Program – focuses on education and access to information. established the CGU’s virtual school courses on : internal control; social control; social control of the government education program and public procurement and contracts. From 2004 to 2009 the virtual school has trained: 7,176 public officials, 8,305 counselors, 8,652 municipal leaderships, 8,709 teachers and students and 586 municipalities participated. The school also designed the Distance Course on Social Control, which presents living examples of active social participation. Belgium ACAs The Belgium Investigations of the Office Central Pour la Repression de la corruption (OCRC) have led to the conviction of a number of highranking officials, politicians and business leaders. Success factors have been the recruitment and training of specialized officers and the building of multi-disciplinary team. The possibility to use special investigative techniques (such as wiretapping) is also an advantage. The Norwegian ACAs Due to the preventive work, good relations have been developed with the private sector. The Anti-corruption Team has successfully prosecuted a number of corruption cases. Most of the cases have been entirely private sector cases. A number of investigations have been related to the oil industry Success -- the CPIO was been able to investigate a number of cases of high-level corruption and detected the infiltration of regional police headquarters and a prosecution office by a criminal organization. According to the Council of Europe the level of police corruption is not increasing to any further extent. The main success factors are good cooperation with the police headquarters and prosecution office and information received from society based on trust in the CPIO. Issues -- the CPIO is not allowed to engage in international police cooperation. Since the CPIO is also investigating politicians, there is sometimes strong political pressure on the CPIO and the Prosecutor General. Such pressure is the main concern of the CPIO. In addition, there is an unclear understanding on corruption within the criminal justice system. Success – Most measures foreseen under the 2002-2004 anti-corruption program have been implemented. A range of prevention and public awareness measures have been carried out. New regional anti-corruption councils have been established. Issues -- Low levels of salaries and the insufficient control capacities within the public administration continue to negatively affect the anti-corruption effort. Success – the achievements are limited to criminal justice operations against bribery, misuse of office, fraudulent bankruptcy or similar. In 2002/2003, 182 persons of active and passive bribery were prosecuted. More than 600 cases were reported but proved to provide insufficient evidence to even start preliminary investigations. Issues -- lack of insufficient interest of young and skilled people to work with USKOK, lack of adequate IT and communication equipment. Given that only the Prosecution Department is operational the department does not receive the support from other departments. • • • • Serious Fraud Office (SFO): arm of the Government of the United Kingdom, accountable to the Attorney-General. Established by the Criminal Justice Act 1987 It investigates fraud and corruption. It has special powers to obtain and assess evidence, to prosecute fraudsters, freeze assets and compensate victims. The SFO has jurisdiction over England and Wales and Northern Ireland but not Scotland, the Isle of Man or the Channel Islands. The SFO acts as the focal point for receiving any allegations of corruption offences by UK nationals or incorporated bodies overseas. It is responsible for the initial review of all allegations received. The City of London Police has a division called the Overseas Anticorruption Unit (OACU) that has a specific function of supporting overseas corruption investigations undertaken by SFO. • The United States has a multi-agency model to fight corruption, with law enforcement agencies at the federal level, the state level, the county level, and the local level. Prosecution takes place at the federal level (US attorneys), the state level (attorneys general), and the county level (prosecutors). US's strong commitment to separation of powers means that anti-corruption efforts can be diffuse and uncoordinated. • Brazil does not have a specialized anti-corruption body. Its high level of decentralization has been reported as one of the main obstacles for the implementation of solid anti-corruption initiatives by the federal government. Several agencies scattered between Brazil's 27 states and 5,651 municipalities have mandates to deal with corruption. Implementation and enforcement deficits of the legal and institutional framework are cited as the main challenges In Australia, the New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) is a good example of a well-functioning sub-national anticorruption agency. The ICAC has jurisdiction over state and local government in New South Wales. This extends to parliamentarians, local councilors, public servants, police and staff of universities and state-owned corporations. Anyone can refer matters to the commission. The commission has the coercive powers of a Royal Commission and can compel witnesses to testify. The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) was established in 2002. The ICAC is accountable to a parliamentary committee which put in place mechanisms that ensure proper checks and balances in the operations of the ICAC. The Parliamentary Committee monitors and reviews the ICAC’s functions: reviews the budgetary estimates of the Commission, and issues such instructions as it considers appropriate with regard to the financial management; the staffing requirements of the Commission, and the allocation of resources to the various operations of the ICAC The Committee is composed of nine members of Parliament. One of the members is designated as Chairperson by the Prime Minister. The Committee meets at least once a month The Committee’s role does not extend to monitoring a matter related to any investigation being carried out by ICAC or the findings of the Commission in relation to a particular investigation. In matters where the Commission is of the view that an investigation has disclosed prima facie evidence against a person and considers prosecution, the matter is referred to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). No prosecution can be instituted by ICAC without the consent of the DPP