NAIRA DEVALUATION: HERE WE GO AGAIN! BY PROFESSOR

advertisement

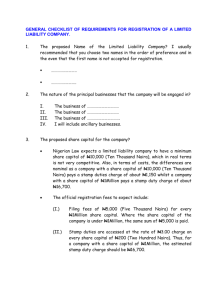

NAIRA DEVALUATION: HERE WE GO AGAIN! BY PROFESSOR EGHOSA OSAGIE, FORMER VICE CHANCELLOR, BENSON IDAHOSA UNVERSITY, BENIN CITY, and FORMER DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH, NATIONAL INSTITUTE, KURU The influence of academics may be thought to be limited to faculty seminar rooms and lecture halls. Rarely is it realized that originators of new academic challenges to orthodox doctrine influence heads of state and presidents regarding the direction of policy and orientation to governance. Not many people are aware that in her years in opposition, Mrs. Thatcher, the brilliant chemist who later studied law, also studied the rudiments of monetarism under the tutelage of Professor Milton Friendman of the University of Chicago. Friendman, as it has now turned out, became the chief priest of monetarism whose main tenets were free market economics, limiting discretionary financial policy by government, the superiority of monetary policy over fiscal policy, and the belief that money matters in macroeconomic analysis. This was in sharp distinction from the analytical conclusions of John Maynard Keynes, who operating from Kings College, Cambridge, propagated the employment of discretionary fiscal policy to stabilize the economy. Keynesianism is widely credited with economic policies which rescued the global economy from the Great Depression of the 1930s. Keynesianism was readily embarrassed by liberal Democrats in the United States, while conservative Republicans were more comfortable with monetarism. The 1980s were years of dramatic changes in global economic policy. Mrs. Thatcher the British Prime Minister, found a ready ally in President Reagan, and both successfully influenced the World Bank and the IMF to design a monetarist economic policy framework in the form of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP) to address economic problems of sub-saharan African countries. These policies were widely applied in the 1980s and beyond. Indeed, aspects of SAP are still being implemented in Nigeria in spite of the fact that it compounded rather than ameliorated economic problem. A key component that has refused to go away is devaluation/depreciation of the naira. To explain this puzzle, we shall be specific. During the first two decades after Independence, Nigeria as well as the rest of the world operated a system of fixed exchange rates. For much of that period, the price of one US dollar was below 70 kobo. The Central Bank managed the allocation of foreign exchange under foreign exchange control regulations. When the system was subjected to corrupt practices during the Second Republic, the World Bank and the IMF recommended devaluation of the naira in 1982. After a detailed analysis of the situation by economists invited by Professor Emma Edozien to advise Government, it was agreed that devaluation was not the appropriate policy response. Government accepted this recommendation. The appropriate response, in our view, was control of corruption which unfortunately was not considered, as the 1979 Constitution was corruption-friendly. Even when the balance-of-payments situated assumed crisis dimensions during the short-lived Buhari Administration with the price of a barrel of crude oil falling below $10 (ten US dollar), the Federal Government resisted the pressure to devalue. Oil prices are volatile, and it is short sighted to hinge a decision to devalue a currency on their movements. Then came the famous national “debate” on devaluation and the IMF in 1985. In spite of empirical evidence that devaluation would set Nigeria on a slippery slope of economic instability without realizing its stated objectives, the naira was devalued not by a deliberate policy of government, but by bankers acting as authorized dealers in foreign exchange with the Central Bank playing the role of major supplier. The slide in the value of the naira accelerated from about N3.00 to the US dollar, to about N80 to the dollar when the military handed power to politicians (really quasi-military politicians) in 1999. The slide continued unabated during the Fourth Republic, thanks to a defective framework of the foreign exchange market, wide-spread corruption (thanks again to the corruption-friendly nature of the 1999 Constitution) and an unstable foreign exchange market in which devaluation elicits further devaluation. It is unfortunate to note here that the principle of convertibility provides ample opportunities for foreign investors and unpatriotic Nigerians to engage in destabilizing speculation against the naira. The Central Bank by its recent devaluation of the naira clearly indicated preference for protection of external reserves at the expense of the value of the naira. Where do we go from here? If current policies on the naira continue, we should expect further devaluation into the indefinite future. The Government may now rejoice that it can calculate the 2015 budget revenue by multiplying monetized dollars by a higher exchange rate. But prices of goods and services would increases in line with the percentage of devaluation due mainly to the heavy import content of investment and consumption. In this regard, the inflation prospect for 2015 is gloomy. Second, many manufacturing enterprises will collapse due to higher costs which make their business unsustainable. This compounds the current unemployment problem. Third, and most important of all, given the fact that Nigeria imports a large percentage of refined petroleum products due to failure to rehabilitate and/or establish new refineries, the naira cost of imported petroleum products will be prohibitive in 2015. The Government would face an embarrassing dilemma: if it continues to subsidize importation of refined petroleum products, the cost of subsidy may rise to about one-third of the total Federal Government Budget. This is clearly unsustainable. If, however the Federal Government discontinues the subsidy programme, the pump price of petrol may go beyond the N200 mark in 2015, an eventuality that will surely invite negative response from key stakeholders. In an election year, this issue may become the most decisive factor influencing the outcome. Nigeria has spent more than 30 years searching for “an appropriate exchange rate” for the naira. So far, it has experimented with a two-tier market, a unified market, wholesale Dutch Action, Retail Dutch Action and a fixed rate system without safeguards against abuses. Three simultaneous exchange rates in the form of the official rate, the inter/bank rate and the parallel market rate co-exist. Yet, there is no light at the end of the tunnel. Speculators, protected by the principal of convertibility, have beaten the system hands down. There appears one way out, an option the Government has been avoiding like the plague since 1986. This is fixing the exchange rate at an appropriate level with specified bands around parity, re-introducing foreign exchange control measures which ban importation of frivolous luxury items, and controlling destabilizing speculation against the naira. I am sure that greedy foreign partfolio investors, unpatriotic Nigerian businessmen and banks, as well as the World Bank and the IMF will vehemently oppose this proposal. But we must be resolute in the belief that reduced inflow of potentially destabilizing foreign capital is a desirable price to pay for stability in our foreign exchange and stock markets and a more settled macroeconomic environment Prof. Eghosa Osagie, Department of Economics, Banking and Finance, Benson Idahosa University, Benin City. November 29, 2014.