School funding in England Capital funding for schools and shortage

advertisement

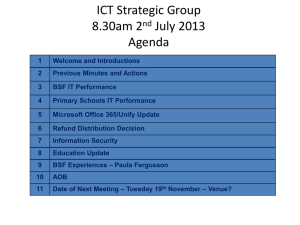

School funding in England Capital funding for schools and shortage of school places September 2013 ________________________________________________________________________ Introduction This briefing sets out recent developments on capital funding for schools, including the key issue of the significant shortage of school places. It also recaps the Government’s decision - shortly after it came into power in 2010 - to scrap the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) Programme. The NUT’s view is that capital funding for schools must be allocated on a needs-led basis to support school buildings that are fit for purpose. We criticised the Government’s decision to scrap the BSF Programme and argue that significant further investment is required to secure the improvements needed in the school building stock. Overview of the current situation Priority School Building Programme The Government set up the Priority School Building Programme (PSBP) in July 2011 through a privately financed partnership known as PF2 – the Government’s new approach to private finance. A limited amount of capital grant was also made available by making savings elsewhere. To commence the PSBP, schools in urgent need of repair were invited to bid for money to carry out renovations or to be rebuilt. In May 2012 the Secretary of State announced that 261 schools were successful in their bids. Delays to the PSBP mean that schools successful via PF2 will not see their new or reconditioned buildings until at least four years after the decision was made to cancel the BSF Programme. Some schools, who found themselves in the uncertain position of being dependent on the 2016 spending review for funding, will have to wait even longer. The Government claims that PSBP will deliver a more efficient, faster and less bureaucratic approach but the concern with low cost, speedier processes and increased efficiencies is that newly built schools will be cheap and substandard. Shortage of school places In addition to the need for repair and refurbishment of schools, there is a growing problem of a shortage of school places. The surge in pupil numbers, following the biggest ten-year increase in the birth rate since the 1950s, has created significant new demands for investment in education just to maintain existing class size levels. A Public Accounts Committee report1 shows that 256,000 school places are needed by September 2014 and the National Audit Office (NAO) forecast that demand is set to rise with a further 400,000 places needed by 2018-19. The NAO published a report2 into capital funding for new school places. The report showed that more than a fifth of primary schools are full or over capacity and large numbers of Local Authorities (LAs) have less funding than they need and children are travelling further to get to school. London councils appear to be feeling the most pressure because of the rising birth rate, fewer pupils going to private schools than in other parts of the country, and fewer families 1 2 Capital funding for new school places: Public Accounts Committee. Published June 2013 Capital funding for new school places: National Audit Office. Published March 2013 SSEE Department September 2013 moving out of the city than had previously. The problem is compounded by the refusal of the Government to allow LAs to open new schools. London Councils’ analysis noted that London accounted for 42 per cent of the future school places need. However, the government had only provided London with 36 per cent of the funding shortfall, leaving LAs to pick up the shortfall to provide each child a school place. The analysis shows that LAs need to fund a further 83,470 school places between 2014 and 2017 — the equivalent of 199 new primary schools or 80 new secondary schools. London Councils said they were spending an extra £1.04 billion on top of extra Government capital funding. Including places they had recently created and those they had yet to pay for, London Councils said they had topped up the Government funding by £9,000 per pupil without a place. Targeted Basic Need Programme It was announced in July 2013 that £820 million will be used to set up the ‘Targeted Basic Need Programme’, which will fund new ‘high quality’ places in locations experiencing the greatest pressure on school places and where a rise in pupil numbers is expected. The Government says the funding is sufficient to provide 417,000 places by 2015. LAs facing a capacity problem will be expected to bid for funding from the Programme to build new schools. New schools set up as part of the Programme, however, have to be free schools or academies and only maintained schools judged as ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ will be eligible for expansion. Under the Programme LAs are to have more power in deciding where these free schools and academies should open, although the final decision will still rest with the Secretary of State as is the case for all new free schools and academies. This represents a move away from the initial ethos around the free school policy - that encouraged parents, teachers and charities to set up free schools - and hints at the pressure on the DfE to address the problem of the shortage of school places. The shortage of school places has featured significantly in the media. Questions have been asked of the DfE by the Education Select Committee, including how the success of the Targeted Basic Need Programme will be measured. Impact of the Government’s free schools policy The ending of BSF came at the same time that the Government was encouraging the expansion of the free schools programme. The NUT was rightly concerned that some of the funding released by cancelled BSF projects could be spent on building new free schools. The NAO noted in its report that the DfE has under-estimated the cost of delivering new places and this is combined with the cut to capital funding by the scrapping of the BSF Programme. The NAO report highlights the problems caused for LAs in planning new places by the Government’s wasteful academies and free schools’ policy and points out that only a third of free school places are in primary schools, where the major increase in pupil numbers will occur. Free schools have opened in areas where there is no ‘basic need’ for places and sometimes where there is a surplus of school places. This is at the same time as some areas are facing a capacity crisis. The NUT believes this is a wasteful use of resources. The DfE needs to take an evidence-based approach to the issue, factoring the real needs of LAs into its spending decisions. Background to the current situation Building Schools for the Future cancellation The previous Government set up two programmes that aimed to rebuild or refurbish every school – the Building Schools for the Future (BSF) Programme and the Primary Capital Programme. BSF was a large scale investment programme that was ambitious in its aims and timescales but was seen as a popular and bold move. SSEE Department September 2013 The £55 billion Programme was, however, criticised for its onerous process, its lack of clear and consistent objectives, the poor design and build quality of a number of schools, the use of Private Finance Initiatives (PFI). Following the general election in 2010 the Government made the unpopular decision to scrap the BSF Programme. The Secretary of State justified the decision on economic and value for money grounds, arguing that the BSF Programme was wasteful and bureaucratic. Amid some confusion and various incorrect published lists of affected schools, it was revealed that some 700 projects would be cancelled. Whilst there were clearly issues with the BSF Programme, its aim to refurbish and rebuild the majority of schools was viewed by the NUT as a vital and long-overdue initiative that sought to address the issue of out of date and dilapidated classrooms and the resultant impact on teaching and learning. The NUT therefore regarded the decision to scrap the Programme as a major setback for schools, teachers and pupils. LAs, especially those only a matter of weeks from starting construction works, incurred significant costs. Several took court action by seeking a Judicial Review. Although the LAs were successful in their action, the court’s decision did not compel the Secretary of State to give the go-ahead to the cancelled projects, though it did require him to look again at the decision for those authorities. The councils put their case to the DfE but Mr Gove only reimbursed the costs for the cancelled projects and did not change his decision. The James Review After the decision to end the BSF Programme the Government set up the ‘James Review’ to look at how the DfE could achieve better value for money. The review3 concluded that there was an urgent need to renew some school buildings that were in a bad state of repair – hence the setting up of the Priority School Building Programme. The ‘Partnership for Schools’ quango that assisted LAs to oversee building projects under BSF transferred its functions to the Education Funding Agency (EFA) from April 2012. The James Review was also critical of the absence of centrally-collated data on the condition of school estates. The Government accepted the Review’s recommendation to collect up-to-date information on the nationwide condition of school buildings and established the Property Data Survey Programme (PDSP). The PDSP is being carried out by the EFA and the results will be available in autumn 2013. The NUT is concerned however that the PDSP specifically excluded an audit of the extent, type and condition of asbestos in schools. Even the most basic repairs are impeded by the presence of asbestos so when schools are refurbished considerable cost overruns can occur through unexpected asbestos remedial and removal work. Excluding asbestos from the survey makes it impossible to make realistic funding estimates and to allocate proportionate resources. 3 Review of Education Capital: Sebastian James. Published April 2011 SSEE Department September 2013