financial administration of the firm fin 5043--930

advertisement

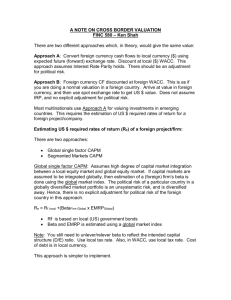

Chapter 9 Risk And Capital Budgeting Professor John Zietlow MBA 621 Chapter 9: Overview • 9.1 Choosing the Right Discount Rate – The cost of equity – The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) – Connecting WACC to the CAPM – Asset betas and project discount rates • 9.2 A Closer Look at Risk – Breakeven analysis – Sensitivity analysis – Scenario analysis and Monte Carlo simulation – Decision trees Chapter 9: Overview (Continued) • 9.3 Real Options – Why NPV doesn’t always give the right answer – Types of real options • Expansion options • Abandonment options • Follow-on investment options – The surprising link between risk and real option values • 9.4 Strategy and Capital Budgeting – Competition and NPV – Strategic thinking and real options • 9.5 Summary Choosing the Right Discount Rate • To calculate an NPV, an analyst must evaluate project’s risk – Often, the best place to look for clues is a firm’s securities • What discount rate should managers use in cap budgeting? – Rate should reflect opportunity cost of all firm’s investors – Rate should also reflect the risk of the specific project • To find discount rate, start with simplifying assumptions: – Assume all equity financing, so only have to satisfy S/Hs – Assume firm makes all investments in a single industry • These allow firm to use cost of equity as discount rate – Know from chapter 6 that cost of equity found with CAPM E ( Ri ) RF βi ( E ( Rm ) RF ) (Eq 9.1) Determining All Leather’s Cost of Equity • All Leather Inc., an all-equity firm, is evaluating a proposal to build a new manufacturing facility – Firm produces leather sofas • As a luxury good producer, firm very sensitive to economy – All Leather’s stock has a beta of 1.3 • Managers note Rf = 4%, believe market’s return will be 9% – Can use CAPM to find All Leather’s cost of equity E(Re ) = Rf + (E(Rm) - Rf) = 4% + 1.3 (9% - 4%) = 10.5% cost of equity • All Leather beta is 1.3 due partly to high economic sensitivity – Higher risk must be reflected in discount rate used to evaluate new manufacturing facility – Low beta company (food processor) would use lower rate Finding All Leather’s Cost of Equity (Cont) • Other factors, besides economic sensitivity, impact beta – A firm’s cost structure & production process very important – Mix of variable & fixed costs determines operating leverage • OL implies CF volatility will rise with fixed cost – Substituting fixed for variable cost increases profits more than proportionally when sales increase, but hurt if sales fall • Define degree of operating leverage (DOL) as % in EBIT divided by % in sales – High DOL: small change in sales large change in EBIT DOL ΔEBIT ΔSales EBIT Sales (Eq 9.2) • Table on next slide details All Leather’s & competitor’s costs & prices – Microfiber also produces sofas, but less fixed costs Financial Data for All Leather Inc. and Microfiber Corp. All Leather Inc Microfiber Corp $10,000,000 $2,000,000 Variable costs per sofa $600 $800 Price $950 $950 Contribution margin $350 $150 40,000 sofas 40,000 sofas $4,000,000 $4,000,000 Fixed costs per year Last year’s sales volume EBIT • Suppose both firms achieve 10% rise in sales volume to 44,000 sofas next year, holding all other figures constant. Fixed cost don’t change. • Both firms’ revenues go from $38,000,000 to $41,800,000; a 10% rise • All Leather’s total costs increase by $600/sofa, or $2,400,000 total • Microfiber’s total costs increase by $800/sofa, or $3,200,000 total • All Leather’s EBIT increases by $350/sofa, $1,400,000 total • Microfiber’s EBIT increases by $150/sofa, $600,000 total Calculating Operating Leverage for All Leather and Microfiber • Using data from previous table, can compute OL for both firms – Note key terms: EBIT= contribution margin - fixed costs – Contribution margin = gross profit per unit of sales – Gross profit = price per unit - variable cost per unit DOLAll Leather = DOLMicrofiber = EBIT Sales $1,400,000 $3,800,000 0.35 0.10 3.5 EBIT Sales $4,000,000 $38,000,000 EBIT Sales $600,000 $3,800,000 0.15 0.10 1.5 EBIT Sales $4,000,000 $38,000,000 • All Leather has a degree of operating leverage (DOL) of 3.5 – EBIT increases by 35% if sales increase by 10% • Microfiber has lower DOL of 1.5 due to lower fixed costs – EBIT increases by only 15% if sales increase by 10% – But firm would weather sales decline better than All Leather Operating Leverage for All Leather and Microfiber EBIT All Leather Microfiber Sales Measuring Financial Leverage and its Impact on Firm’s Stock Beta • Operating leverage: using fixed cost assets to magnify (leverage) impact of change in sales on change in EBIT – Increasing OL yields increasing stock beta • Firms also use fixed cost financing (debt & PS) to magnify effect of given change in EBIT on net income – Measured as degree of financial leverage (DFL) ΔNI ΔEBIT DFL NI EBIT • If sales and EBIT increase, FL will yield magnified rise in NI – But also works on downside; if sales & EBIT fall, so will NI • FL increases expected net profits, but also increases risk – Thus use of FL also increases a firm’s stock beta Measuring Financial Leverage (Cont.) • Demonstrate FL with firms on next table; same except financing – Firm 1: 100% equity, Firm 2: 60% equity, 40% debt – Cost of Firm 2’s debt = 8.5%; assume neither firm pays tax – Both firms have $250mn assets, identical production process • Case #1: Assume both firms generate 25% gross return on assets, or $62.5mn EBIT, and both pay out net income to S/H – Firm 1 pays no interest, so $62.5 mn paid to S/Hs; 25% ROE – Firm 2 pays $8.5mn int, so $54mn paid to S/Hs; 36% ROE • Case #2: Assume both firms generate 5% gross return on assets, $12.5mn EBIT; again both pay out net income to S/H – Firm 1 pays no interest, so $12.5 mn paid to S/Hs; 5% ROE – Firm 2 pays $8.5mn int, so only $4mn paid to S/Hs; 2.7% ROE • If EBIT high, FL increases ROE; decreases ROE if EBIT low The Effect Of Financial Leverage on Shareholder Returns Assets Debt Equity Firm 1 Firm 2 $250 million $250 million $0 $100 million $250 million $150 million Case #1: Gross Return on Assets Equals 25 Percent EBIT Interest Cash to equity ROE $62.5 million $62.5 million $0 $8.5 million $62.5 million $54 million 62.5 ÷ 250 = 25% 54 ÷ 150 = 36% Case #2: Gross Return on Assets Equals 5 Percent EBIT Interest Cash to equity ROE $12.5 million $12.5 million $0 $8.5 million $12.5 million $4 million 12.5 ÷ 250 = 5% 4 ÷ 150 = 2.7% The Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) • Cost of equity the right discount rate for all-equity firm – But what if firm has both debt and equity? – Problem akin to finding expected return of portfolio • Use weighted avg cost of capital (WACC) as discount rate – Let D and E represent market values of debt & equity • Demonstrate using Comfy Inc’s capital structure – Comfy Inc builds residential houses – Firm has $150mn equity (E), with cost of equity re = 12.5% – Also has bonds (D) worth $50mn O/S, with rd = 6.5% – Calculate WACC = 11% D E 50 150 WACC rd re 6.5% 12.5% DE DE 50 150 50 150 50 150 6 . 5 % 12.5% 0.256.5% 0.7512.5% 11% 200 200 Finding the WACC (Cont) • How can Comfy’s managers be sure WACC = 11%? – First way: assume wealthy investor purchases all firm’s debt and equity. This is return he/she would earn • Second way: Suppose firm invests in a project earning 11% and distributes return to investors. Will they be satisfied? – Following table shows CF generated & distributed satisfies claims Cash distributions to Comfy investors Total CF available to distribute ($200m x 11%) $22 million Interest owed on bonds ($50m x 6.5%) $3.25 million Cash available to shareholders ($22m - $3.25m) $18.75 million Rate of return earned by S/Hs ($18.75m ÷ $150m) 12.5% Finding WACC for Firms with Complex Capital Structures • How to calculate WACC if firm has long-term (LT) debt as well as preferred (P) & common stock (E)? – Find weighted average of individual capital costs E LT P WACC re rd rp EDP E D P EDP • Assume S.N. Sherwin Co. wants to determine its WACC – Has 10,000,000 common shares O/S; price = $15/sh; rc = 15% – Has $40mn L-T, fixed rate notes with 8% coupon rate, but 7% YTM; notes sell at premium and worth $49mn – Has 500,000 pref shrs, 8% coupon, $75price, $12.5mn value • Total value = $150m E+ $49m LT+$12.5m P =$211.5m 150 49 12.5 WACC 15 % 7 % 8% 12.73% 211.5 211.5 211.5 Connecting the WACC to the CAPM • Developed separately, but WACC consistent with CAPM – Have so far looked only at all-equity firm – But can use CAPM to compute WACC for levered firm • Calculate beta for bonds of a large corporation – First find covariance between bonds & stock market, then – Plug computed debt beta (d), Rf & Rm into CAPM to find rd • Debt beta typically quite low for healthy, low-debt firms – Debt beta rises with leverage, approaches equity beta in B/R rd Rf d ( RM Rf ) 4% 0.1 (12.5% 4%) 4.85% • Example shows CAPM can be used for any security – Any asset that generates a CF has a beta, and that beta determines its required return as per CAPM Calculating Asset Betas and Equity Betas • The CAPM establishes direct link between required return on D & E and betas of these securities • Beta of firm’s assets equals weighted avg of D & E betas βA ( D E ) βd ( ) βe DE DE (Eq 9.4) • A firm’s asset beta thus equals the cov of firm’s CFs with RM, return on market p/f, divided by var of market’s return – For all-equity firm, asset beta = equity beta – For levered firm, asset beta will be less than equity beta • If asset beta known, and debt beta is assumed to be 0, can compute equity beta directly from A βE β A (1 D ) E (Eq 9.5) Finding Equity Betas from Asset Betas, and Vice Versa • If market values of D & E known, and any two of the three betas are known, can compute the other beta – Usually assume debt beta known (say d = 0.15) • Assume firm has manufacturing assets with asset beta = 1.2 – If firm unlevered, equity beta equals asset beta, E = A =1.2 – Now suppose firm decides to raise 20% of funding needs by issuing relatively safe bonds (d = 0.15) & retiring equity – Use Eq 9.4 to find E, given A = 1.2 and d = 0.15 A 1.2 (0.2)(0.15) (0.8) E 1.2 (0.2)(0.15) E 1.46 0.8 Finding Equity Betas from Asset Betas, and Vice Versa (Cont) • Can only use Eq 9.5 if debt beta assumed = 0 – Since debt = 20% of capital and equity = 80%, the debt-toequity ratio D/E = 0.2 ÷ 0.8 = 0.25 – Not surprisingly, equity beta is higher if debt beta assumed 0 E A 1 D 0.2 1.21 1.21.25 1.5 E 0.8 • Can now state decision rule for determining discount rate to use for projects with asset betas similar to firm’s own – For all equity firm, use cost of equity given by CAPM – For levered firm, use WACC computed using CAPM and betas of individual capital components • If a project’s asset beta differs from firm’s asset beta, must compute and use project betas Finding the Discount Rate to Use for Projects Unrelated to Firm’s Industry • What if a company has diversified investments in many industries? – In this case, using firm’s WACC to evaluate an individual project would be inappropriate – Instead use project’s asset beta adjusted for desired leverage • Assume GE evaluating an investment in oil & gas industry – Much different from any of GE’s existing businesses – Instead GE would examine existing firms that are pure plays – These are public firms operating only in O&G industry • Say GE selects Berry Petroleum & Forest Oil as pure plays – Operationally similar firms, but Berry Petroleum’s E = 0.65 and Forest Oil’s E = 0.90; why so different? – Reason: Forest uses debt for 39% of financing; Berry: 14% – Even if core business the same risk (A equal), E will differ Data for Berry Petroleum and Forest Oil Berry Petroleum Forest Oil Stock beta 0.65 0.90 Fraction Debt 0.14 0.39 Fraction Equity 0.86 0.61 D/E ratio 0.16 0.64 Asset beta * 0.56 0.55 • Computed using Eq 9.4 and assuming debt beta = 0 Berry Petrol: A = (%D)d + (%E)E = (0.14)(0) + (0.86)(0.65) = 0.56 Forest Oil: A = (%D)d + (%E)E = (0.39)(0) + (0.61)(0.90) = 0.55 Converting Equity Betas to Asset Betas for Two Pure Play Firms • To determine correct A to use as discount rate for O&G project, GE must convert pure play E to A, then average – Previous table lists data needed to compute unlevered equity beta – Unlevered equity beta (same as A) strips out effect of financial leverage, so always less than or equal to equity beta – Berry’s A = 0.56, Forest’s A = 0.55, so average A = 0.55 • GE capital structure consists of 20% debt and 80% equity (D/E ratio = 0.25). Compute relevered equity beta: GE A 1 D 0.551 0.25 0.69 E Converting Equity Betas to Asset Betas for Two Pure Play Firms (Continued) • Assume risk-free rate of interest is 6% and expected risk premium on the market is 7% – Using CAPM equation, compute rate of return GE shareholders require for the oil and gas investment E(R) = 6% + 0.69(7%) = 10.83% – One more step to find the right discount rate for GE’s investment in this industry – calculate project WACC – GE’s financing is 80% equity and 20% debt. Assume investors expect 6.5% on GE’s bonds E D WACC re rd 10.83%(80%) 6.5%( 20%) 9.96% DE DE Summarizing Rules for Selecting an Appropriate Project Discount Rate • When an all equity firm invests in an asset similar to its existing assets, the cost of equity is the appropriate discount rate to use in NPV calculations. • When a levered firm invests in an asset similar to its existing assets, the WACC is the right discount rate. • When a firm invests in an asset that is different than its existing assets, it should look for pure play firms to find the right discount rate. – Firms can calculate an industry asset beta by unlevering the betas of pure play firms – Given the industry asset beta, firms can determine an appropriate discount rate using the CAPM Accounting for Taxes in Finding WACC • Have thus far assumed away taxes, but often important – Tax deductibility of interest payments favors use of debt – Accounting for interest tax shields yields after-tax WACC D E WACC (1 T )rd re D E D E (Eq 9.6) • Can likewise present method of computing after-tax equity beta from asset beta – Again assuming debt beta = 0, equity beta given by eq below – Accounting for taxes doesn’t change key lessons above E A 1 (1 T ) D E (Eq 9.7) A Closer Look at Risk Break-Even Analysis • Managers often want to assess business’ key value drivers – Key to assessing operating risk is finding break-even point • Break-even point (BEP) is level of output where all operating costs (fixed and variable) are covered – BEP found by dividing FC by contribution margin (CM) Fixed Costs FC BEP Contributi on m arg in Pr ice / unit VC / unit • Use this to find BEP for All Leather & Microfiber – All Leather: FC = $10,000,000; Pr = $950/un; VC = $600/un – Microfiber: FC = $2,000,000; Pr = $950/un; VC = $800/un $10,000,000 $10,000,000 BEPAllLeather 28,572 sofas $350 $950 $600 $2,000,000 $2,000,000 BEPMicrofiber 13,334 sofas $950 $800 $150 Break-Even Point for All Leather Costs & Revenues Total revenue Total costs $10,000,000 Fixed costs 28,572 units Units All Leather has high fixed costs ($10,000,000), but also high contribution margin ($350/sofa). High BEP, but once FC covered, profits grow rapidly. Break-Even Point for Microfiber Costs & Revenues Total revenue Total costs Fixed costs $2,000,000 13,334 units Units Microfiber has low fixed costs ($2,000,000), but also low contribution margin ($150/sofa). Low BEP, but profits grow slowly after FC covered. Sensitivity Analysis • Sensitivity analysis allows mangers to test importance of each assumption underlying a forecast – Test deviations from “base case” and associated NPV • Best Electronics Inc (BEI) has new DVD players project. Base case assumptions (below) yields Exp NPV = $1,139,715 – – – – – – – – – – – The project’s life is five years. The project requires an up-front investment of $41 million. BEI will depreciate initial investment on S-L basis for five years One year from now, DVD industry will sell 3,000,000 units Total industry unit volume will increase by 5% per year. BEI expects to capture 10% of the market in the first year BEI expects to increase its market share one percentage point each year after year one. 8. The selling price will be $100 in year one. 9. Selling price will decline by 5% per year after year one. 10. Variable production costs will equal 60% of the selling price. 11. The appropriate discount rate is 14 percent. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Sensitivity Analysis of DVD Project NPV -$448,315 Pessimistic Assumption $43,000,000 Initial investment Optimistic $39,000,000 NPV +2,727,745 -$1,106,574 2,800,000 un Market size in year 1 3,200,000 un +3,386,004 -$640,727 8% per year +3,021,884 12% +6,882,262 2% per year +6,121,315 $110 +4,509,149 2% per year Growth in market size -$4,602,832 8% -$3,841,884 Zero Growth in market share -$2,229,718 $90 Initial selling price -$545,002 Initial market share 62% of sales Variable costs -$2,064,260 -10% per yr Annual price change -$899,413 16% Discount rate 58% of sales +2,824,432 0% per year +4,688,951 12% +3,348,720 If all optimistic scenarios play out, project’s NPV rises to $37,635,010. If all pessimistic scenarios play out, project’s NPV falls to -$19,271,270! Using Decision Trees to Make Multi-Step Investment Decisions • Many real investment projects are conditional & multistage: will only proceed to stage 2 if stage 1 successful – Occurs frequently with new product introductions – Begin selling in test market; if successful, build factory for full-scale production & nationwide roll-out – Very hard to evaluate in standard cap budgeting framework • Decision trees allow managers to break investment analysis into distinct phases – Forces managers to perform extended “if--then” analysis • Assume Trinkle Foods (Canada) has invented new salt substitute, Odessa; assessing market testing in Vancouver – Market test will cost C$5 million, but no new facilities needed – If test successful, Trinkle will spend additional C$50mn to build factory and launch nationwide one year later Using Decision Trees (Cont) • If market test successful, Trinkle predicts full product launch will generate +C$12mn NCF per year for 10 years – If test unsuccessful, expect full product launch to generate only +C$2 mn NCF per year for 10 years. – If Trinkle’s WACC=15% should Trinkle invest? If so, in what? • Next figure shows decision tree for investment problem – Initially, firm can choose to spend C$5 mn on market test – If market test executed, expect probability of success = 0.5 • Proper way to use tree: begin at end & work backwards – Suppose in one year, Trinkle learns test is successful. – At that point, the NPV of launching the product is: NPV 50 12 12 12 12 ... 10.23 1.15 1.15 2 1.15 3 1.1510 • Clearly, Trinkle would invest if it winds up on this branch Decision Tree From Odessa Investment Using Decision Trees (Cont) • But what if the initial tests are unfavorable? – In that case, project’s NPV equals -C$39.96 mn & firm should walk away--not fund nationwide roll-out. – Note that C$5 mn test market cost is a sunk cost at t=1, so the NPV of doing nothing at time one is zero 2 2 2 2 NPV 50 ... 39.96 2 3 10 1.15 1.15 1.15 1.15 • Now have set of simple “if--then” decision rules from tree – If test successful, launch nationwide and NPV = C$10.23 mn – If test unsuccessful, don’t invest C$50 mn for national launch Using Decision Trees (Cont) • Now must decide (at t=0) whether to spend C$5 mn for test – Must realize NPVs computed at t=1 and use prob (success) 10.23 0 NPV 5 0.5 0 . 5 0.55 1.15 1.15 • Seems unwise to invest in market test – But very sensitive to discounting future CF at 15% rate – Since test results known t=1, may use lower rate afterwards Real Options in Capital Budgeting • Though decision trees helpful in examining multi-stage projects, most promising method is option pricing analysis – Imbedded options arise naturally from investment – Called real options to distinguish from financial options – Options are valuable rights, not obligations • Can transform negative NPV projects into positive NPV – Value of a project equals value captured by NPV, plus option • Several types of real options frequently encountered: 1. Expansion options: If a product is a hit, expand production 2. Abandonment options: Can abandon a project if not successful; S/Hs have valuable option to default on debt 3. Follow-on investment options: Similar to expansion options, but more complex (Ex: movie rights to sequel) 4. Flexibility options: Ability to use multiple production inputs (Ex: dual-fuel industrial boiler) or produce multiple ouputs