Lecture Five Francis Bacon Brief Introduction of Bacon's Life

advertisement

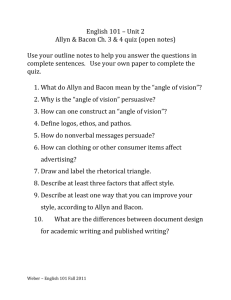

Lecture Five Francis Bacon I. • • • • • Brief Introduction of Bacon’s Life Francis Bacon (1561-1626), the founder of English materialist philosophy. Bacon was born in the family of Sir Nicholas Bacon, Keeper of Privy Seal to Queen Elizabeth. He went to Cambridge at 12 and, after graduating at 16, took up law. At 23 he became a member of the House of Commons. He was convicted, deprived of his office, fined and banished from London, in 1621. Five years later, he died in aged disgrace. II. Bacon’s Major Works Bacon was the founder of modern science in England, his "Advancement of Learning”(1605), " New Instrument”(1620), a statement of what is called the Inductive Method of reasoning. • Bacon is also famous for his "Essays" . Ten of them were published in 1597, as notes of his observations. The collection was reissued and enlarged in 1612 and again in 1625, when it included 58 essays. III. More about Bacon • Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount Saint Alban, (22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist and author. He famously died of pneumonia contracted while studying the effects of freezing on the preservation of meat. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Although his political career ended in disgrace, he remained extremely influential through his works, especially as philosophical advocate and practitioner of the scientific method and pioneer in the scientific revolution. • Bacon has been called the father of empiricism. His works established and popularized deductive methodologies for scientific inquiry, often called the Baconian method or simply, the scientific method. His demand for a planned procedure of investigating all things natural marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, much of which still surrounds conceptions of proper methodology today. His dedication probably led to his death so bringing him into a rare historical group of scientists who were killed by their own experiments. • Bacon was knighted in 1603, created Baron Verulam in 1618, and Viscount St Alban in 1621; as he died without heirs both peerages became extinct upon his death. • Bacon's Utopia • In 1623 Bacon expressed his aspirations and ideals in New Atlantis. Released in 1627, this was his creation of an ideal land where "generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendor, piety and public spirit" were the commonly held qualities of the inhabitants of Bensalem. In this work, he portrayed a vision of the future of human discovery and knowledge. The plan and organization of his ideal college, "Solomon's House", envisioned the modern research university in both applied and pure science. • Baconian method • The Novum Organum is a philosophical work by Francis Bacon published in 1620. The title is a reference to Aristotle's work Organon, which was his treatise on logic and syllogism. In Novum Organum, Bacon detailed a new system of logic he believed to be superior to the old ways of syllogism. In this work, we see the development of the Baconian method (Or scientific method), consisting of procedures for isolating the form, nature or cause of a phenomenon, employing the method of agreement, method of difference, and method of concomitant variation devised by Avicenna in 1025. IV. The characteristics of Bacon’s Essays • Firstly, the literary form was new to the English audience. It was the French philosopher Montaigne who first called his prose pieces essays. • But different from Montaigne’s personal and informal style, Bacon’s style is more formal and more tightly organized. • Secondly, these essays cover a variety of subjects, ranging from abstract subjects to concrete, practical matters. • Thirdly, these essays, though short, are sinewy, full of wisdom, and elegantly phrased. • Fourthly, Bacon’s essays are compact in style, clear in expression and profound in thoughts. V. Of Studies • STUDIES serve for delight, for ornament, and for ability. Their chief use for delight, is in privateness and retiring; for ornament, is in discourse; and for ability, is in the judgment, and disposition of business. For expert men can execute, and perhaps judge of particulars, one by one; but the general counsels, and the plots and marshalling of affairs, come best, from those that are learned. To spend too much time in studies is sloth; to use them too much for ornament, is affectation; to make judgment wholly by their rules, is the humor of a scholar. They perfect nature, and are perfected by experience: for natural abilities are like natural plants, that need proyning, by study; and studies themselves, do give forth directions too much at large, except they be bounded in by experience. Crafty men contemn studies, simple men admire them, and wise men use them; for they teach not their own use; but that is a wisdom without them, and above them, won by observation. • Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested; that is, some books are to be read only in parts; others to be read, but not curiously; and some few to be read wholly, and with diligence and attention. Some books also may be read by deputy, and extracts made of them by others; but that would be only in the less important arguments, and the meaner sort of books, else distilled books are like common distilled waters, flashy things. Reading maketh a full man; conference a ready man; and writing an exact man. • And therefore, if a man write little, he had need have a great memory; if he confer little, he had need have a present wit: and if he read little, he had need have much cunning, to seem to know, that he doth not. Histories make men wise; poets witty; the mathematics subtle; natural philosophy deep; moral grave; logic and rhetoric able to contend. Abeunt studia in mores. Nay, there is no stond or impediment in the wit, but may be wrought out by fit studies; like as diseases of the body, may have appropriate exercises. Bowling is good for the stone and reins; shooting for the lungs and breast; gentle walking for the stomach; riding for the head; and the like. So if a man's wit be wandering, let him study the mathematics; for in demonstrations, if his wit be called away never so little, he must begin again. If his wit be not apt to distinguish or find differences, let him study the Schoolmen; for they are cymini sectores. If he be not apt to beat over matters, and to call up one thing to prove and illustrate another, let him study the lawyers' cases. So every defect of the mind, may have a special receipt. 5.1 What is Francis Bacon Of Studies about? • "Of Studies" is an essay written to inform us of the benefits of studying. Studying is applying the mind to learning and understanding a subject, especially through reading, which is perhaps why by 'studying', Sir Francis Bacon mostly refers to reading. In his short essay, he strives to persuade us to study, and tells us how to study if we are to make the best of what we read. He does this by using many rhetorical devices and substantiations to prove his arguments. • 'Of Studies' main point is to be evidence for the benefits of studying. Sir Francis Bacon attempts to prove to us that "studies serve for delight, for ornament and for discourse" by showing us how education is used and can be used in our lives. 5.2. What are the outline of Of Studies? • Bacon explains how and why study - a.k.a. knowledge - is important. He lays out the value of knowledge in practical terms. Bacon considers to what use studies might be put. He is less interested in their theoretical promise than in their practical utility. His writing is direct and pointed. It avoids the meandering find-your-way free form of other essays. Francis gets to the point in his opening sentence, "Studies serve for delight, for ornament, and for ability." He then elaborates on how studies are useful in these three ways. And he wastes no words in detailing the uses of "studies" for Renaissance gentlemen. • One of the attractions of Bacon's essay is his skillful use of parallel sentence structure, as exemplified in the opening sentence and through "Of Studies." This stylistic technique lends clarity and order to the writing, as in "crafty men condemn studies, simple men admire them, and wise men use them," which in its straightforward assertiveness exhibits confidence and elegance in addition to clarity and emphasis. 5.3. (译文)谈读书 • 培根 • 读书足以怡情,足以傅彩,足以长才。其怡情也,最 见于独处幽居之时;其傅彩也,最见于高谈阔论之中;其 长才也,最见于处世判事之际。练达之士虽能分别处理细 事或一一判别枝节,然纵观统筹、全局策划,则舍好学深 思者莫属。读书费时过多易惰,文采藻饰太盛则矫,全凭 条文断事乃学究故态。读书补天然之不足,经验又补读书 之不足,盖天生才干犹如自然花草,读书然后知如何修剪 移接;而书中所示,如不以经验范之,则又大而无当。有 一技之长者鄙读书,无知者羡读书,唯明智之士用读书, 然书并不以用处告人,用书之智不在书中,而在书外,全 凭观察得之。读书时不可存心诘难作者,不可尽信书上所 言,亦不可只为寻章摘句,而应推敲细思。书有可浅尝者, 有可吞食者,少数则须咀嚼消化。换言之,有只须读其部 分者,有只须大体涉猎者,少数则须全读,读时须全神贯 注,孜孜不倦。书亦可请人代读,取其所作摘要,但只限 题材较次或价值不高者,否则书经提炼犹如水经蒸馏、淡 而无味矣。 • 读书使人充实,讨论使人机智,笔记使人准确。 因此不常作笔记者须记忆特强,不常讨论者须天 生聪颖,不常读书者须欺世有术,始能无知而显 有知。读史使人明智,读诗使人灵秀,数学使人 周密,科学使人深刻,伦理学使人庄重,逻辑修 辞之学使人善辩:凡有所学,皆成性格。人之才 智但有滞碍,无不可读适当之书使之顺畅,一如 身体百病,皆可借相宜之运动除之。滚球利睾肾, 射箭利胸肺,慢步利肠胃,骑术利头脑,诸如此 类。如智力不集中,可令读数学,盖演题须全神 贯注,稍有分散即须重演;如不能辨异,可令读 经院哲学,盖是辈皆吹毛求疵之人;如不善求同, 不善以一物阐证另一物,可令读律师之案卷。如 此头脑中凡有缺陷,皆有特药可医。 VI. Of Truth • WHAT is truth? said jesting Pilate,and would not stay for an answer. Certainly there be, that delight in giddiness, and count it a bondage to fix a belief; affecting free-will in thinking, as well as in acting. And though the sects of philosophers of that kind be gone, yet there remain certain discoursing wits, which are of the same veins, though there be not so much blood in them, as was in those of the ancients. But it is not only the difficulty and labor, which men take in finding out of truth, nor again, that when it is found, it imposeth upon men's thoughts, that doth bring lies in favor; but a natural, though corrupt love, of the lie itself. • One of the later school of the Grecians, examineth the matter, and is at a stand, to think what should be in it, that men should love lies; where neither they make for pleasure, as with poets, nor for advantage, as with the merchant; but for the lie's sake. But I cannot tell; this same truth, is a naked, and open day-light, that doth not show the masks, and mummeries, and triumphs, of the world, half so stately and daintily as candle-lights. Truth may perhaps come to the price of a pearl, that showeth best by day; but it will not rise to the price of a diamond, or carbuncle, that showeth best in varied lights. A mixture of a lie doth ever add pleasure. Doth any man doubt, that if there were taken out of men's minds, vain opinions, flattering hopes, false valuations, imaginations as one would, and the like, but it would leave the minds, of a number of men, poor shrunken things, full of melancholy and indisposition, and unpleasing to themselves? • One of the fathers, in great severity, called poesy vinum daemonum, because it fireth the imagination; and yet, it is but with the shadow of a lie. But it is not the lie that passeth through the mind, but the lie that sinketh in, and settleth in it, that doth the hurt; such as we spake of before. But howsoever these things are thus in men's depraved judgments, and affections, yet truth, which only doth judge itself, teacheth that the inquiry of truth, which is the love-making, or wooing of it, the knowledge of truth, which is the presence of it, and the belief of truth, which is the enjoying of it, is the sovereign good of human nature. The first creature of God, in the works of the days, was the light of the sense; the last, was the light of reason; and his sabbath work ever since, is the illumination of his Spirit. First he breathed light, upon the face of the matter or chaos; then he breathed light, into the face of man; and still he breatheth and inspireth light, into the face of his chosen. The poet, that beautified the sect, that was otherwise inferior to the rest, saith yet excellently well: It is a pleasure, to stand upon the shore, and to see ships tossed upon the sea; a pleasure, to stand in the window of a castle, and to see a battle, and the adventures thereof below: but no pleasure is comparable to the standing upon the vantage ground of truth (a hill not to be commanded, and where the air is always clear and serene), and to see the errors, and wanderings, and mists, and tempests, in the vale below; so always that this prospect be with pity, and not with swelling, or pride. Certainly, it is heaven upon earth, to have a man's mind move in charity, rest in providence, and turn upon the poles of truth. • To pass from theological, and philosophical truth, to the truth of civil business; it will be acknowledged, even by those that practise it not, that clear, and round dealing, is the honor of man's nature; and that mixture of falsehoods, is like alloy in coin of gold and silver, which may make the metal work the better, but it embaseth it. For these winding, and crooked courses, are the goings of the serpent; which goeth basely upon the belly, and not upon the feet. There is no vice, that doth so cover a man with shame, as to be found false and perfidious. And therefore Montaigne saith prettily, when he inquired the reason, why the word of the lie should be such a disgrace, and such an odious charge? Saith he, If it be well weighed, to say that a man lieth, is as much to say, as that he is brave towards God, and a coward towards men. For a lie faces God, and shrinks from man. Surely the wickedness of falsehood, and breach of faith, cannot possibly be so highly expressed, as in that it shall be the last peal, to call the judgments of God upon the generations of men; it being foretold, that when Christ cometh, he shall not find faith upon the earth. (译文)谈真理 王佐良译 • 真理何物?皮拉多笑而问曰,未待人答,不顾而去。确有 见异思迁之徒,以持见不变为束缚,而标榜思想与行动之 自由意志。先哲一派曾持此见,虽已逝去,尚有二三散漫 书生依附旧说,唯精力已大不如古人矣。固然,真理费力 难求,求得之后不免限制思想,唯人之爱伪非坐此一因, 盖由其天性中原有爱伪之劣念耳。希腊晚期学人审问此事, 不解人为何喜爱伪说,既不能从中得乐,如诗人然,又不 能从中获利,如商人然,则唯有爱伪之本体而已。余亦难 言究竟,唯思真理犹如白日无遮之光,直照人世之歌舞庆 典,不如烛光掩映,反能显其堂皇之美。真理之价,有似 珍珠,白昼最见其长,而不如钻石,弱光始露其妙。言中 有伪,常能更增其趣。 • 盖人心如尽去其空论、妄念、误断、怪想,则仅余一萎缩 之囊,囊中尽装怨声呻吟之类,本人见之亦不乐矣!事实 如此,谁复疑之?昔有长老厉责诗歌,称之为魔鬼之酒, 即因其扩展幻想,实则仅得伪之一影耳。为害最烈者并非 飘略人心之伪,而系滞留人心之伪,前已言及。然不论人 在堕落时有几许误断妄念,真理仍为人性之至善。盖真理 者,唯真理始能判之,其所教者为求真理,即对之爱慕; 为知真理,即得之于心;为信真理,即用之为乐。上帝创 世时首创感觉之光,末创理智之光,此后安息而显圣灵。 先以光照物质,分别混沌;次以光照人面,对其所选之人 面更常耀不灭。古有诗人信非崇高,言则美善,曾有妙语 云: “立岸上见浪催船行,一乐也;立城堡孔后看战斗 进退,一乐也;然皆不足以比身居真理高地之乐也;真理 之峰高不可及,可吸纯洁之气,可瞰谷下侧行、瞭徨、迷 雾、风暴之变”。景象如此,但须临之以怜世之心,而不 可妄自尊大也。人心果能行爱心,安天命,运转于真理之 轴上,诚为世上天国矣。 • 如自神学哲学之真理转论社会事务,则人无论遵 守与否,皆识一点,即公开正直之行为人性之荣, 如掺伪则如金银币中掺杂,用时纵然方便,其值 大贬矣。盖此类歪斜之行唯毒蛇始为,其因无公 行之足,唯有暗爬之腹也。恶行之中,令人蒙羞 最大者莫过于虚伪背信。谎言之为奇耻大辱也, 蒙田探究真理,曾云:“如深究此事,指人说谎 犹言此人对上帝勇而对人怯也,盖说谎者敢于面 对上帝,而畏避世人”。善哉此言。虚伪背信之 恶,最有力之指责莫过于称之为向上帝鸣最后警 钟,请来裁判无数世代之人,盖圣经早已预言, 基督降世时,“世上已无信义可言矣”。 III. Answer the following question. . What is the writing style of Bacon’s essays? • Clearness, brevity and force of expression are peculiar to Bacon’s essays. • His sentences are short, pointed, incisive and often of balanced structure. • Or simply we can say directness, terseness and forcefulness. • Parallelism is most often used.