Paper for publication - University of Warwick

advertisement

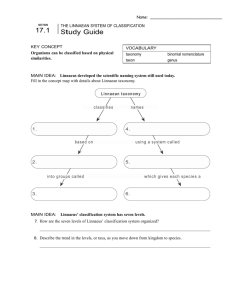

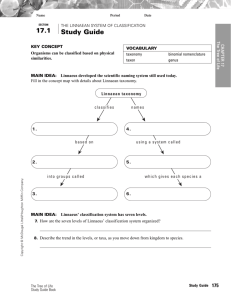

1 Circulating Knowledge on Nature: Travellers and Informers in Linnaean Natural History1 Hanna Hodacs This essay is concerned with the circulation of natural history knowledge in the second half of the eighteenth-century, a period in which the Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1778) played a central role. Linnaeus was a professor of medicine at the University of Uppsala and a node in the Republic of Letters, the largely European based network of eighteenth-century scholars. This was a position he reached developing his new and systematic ways to name, describe and categorise species, particularly plant species. The binominal names, Linnaeus’ new scientific nomenclature, giving species short and easy-toremember names, has survived until today while his sexual system, in which the reproductive parts of the plant and their constellations provided “keys” with which help naturalists could infer the identity of a plant, is long outdated. At the time though the sexual system and Linnaeus’ other taxonomic innovations were of great assistance identifying, naming and describing old and new plants. The growing number of new species arriving to Europe from Asia, America, Africa and the Pacific world reflects on the expanding European influence across the globe. However, while there is no doubt that Linnaean natural history benefitted from the advancement of European power and vice versa the history of the connection between Linnaean scholarship and global economics and politics is somewhat underexplored. Aside from Linnaeus’ intellectual input, celebrated in traditional accounts (e.g. Fries) and problematized in more modern, as Koerner most recently has explored Linnaeus was deeply sceptical to long distance trade and its’ economic implication, there have been relatively few attempt to analyse how Linnaeus’ work could have such an impact. What work there are have generally been addressing issues to do with communication, collaboration and paper technologies (Dietz , Müller-Wille, Müller-Wille & Charmantier). The aim with this essay is look beyond Linnaeus focusing particularly on the tradition of travelling within Linnaean natural history and how it can explain the ever growing circulation of knowledge on nature that followed in the wake of Linnaeus’ work. The main focus is on the agency of travelling naturalists connected to Linnaeus, what enabled them to travel, why they travelled and how knowledge was generated and circulated along the road. Travelling was a central feature in Linnaean natural history. Linnaeus travelled long distances himself; soon after graduation and before heading to the Dutch Republic he made a solo tour of Northern Sweden including Finland.2 Compared to the journeys of many of his students Linnaeus’ travelling experience was however somewhat limited. The map below illustrates the extent of some of these journeys namely the most famous ones undertaken by a group of individuals often referred to as Linnaeus’ “Apostles” or “Disciples”. Many of these journeys were part of well-known expeditions, 1 The discussion in the article is based on research conducted within two project both sponsored by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet). On the first one, Learning and Teaching in the Name of Science – A Study of Linnaeus and His Students, I worked closely together with Kenneth Nyberg. The product of this collaboration (Hodacs and Nyberg) form a corner stone in the discussion here and I would like to acknowledge Nyberg’s input to many of the ideas presented below (although mistakes and errors are of course my own). I would also like to thank Kenneth for his comments to earlier versions of this essay. The second project, Westward Science between 1760-1810; on Social Mobility and the Mobility of Science, is a project of my own design which focus on Swedish naturalists working in London or on behalf of British institutions elsewhere. 2 The life and work of Linnaeus has been the subject of many studies, one of the most recent in English is Koerner’s which discusses Linnaeus’ work in the light of early modern political economy. For a more general introduction to Linnaeus see Blunt. 2 such as those headed by Captain James Cook in the 1760s and 1770s, or those organised by Russia as part of the exploration of its Eastern borderland in the eighteenth-century. Others reflect on the Eurasian trade with particularly China and South East Asia conducted by the East India companies of Sweden and the Dutch Republic. Map from Tord Wallström, Svenska Upptäckare, Höganäs: Bra Böcker, 1982, pp. 84-85, Copyright Tord Wallström. That the new Linnaean principles for how to identify, categorise and name plants and animals were diffused in the wake of the journeys described by the map and that European knowledge of nature across the globe consequently increased is not a particularly controversial assumption. This essay will also examine some of the more famous long distance journeys from this point of view, the main focus of attention is however on the phenomena of Linnaean travelling more generally, including the less well known cases of shorter journeys and excursions inside Sweden and around Uppsala. This geographically inclusive approach, and what it entails in terms of highlighting important factors and circumstances, will help us explore what was a complex relationship between travelling and knowledge circulation. The essay will start with a discussion of the natural history education Linnaeus’ students received focusing particularly on the role of travelling as a form of education and graduation which turned early modern students into scholars. Emphasis will be on the agency of the individual student, what sort of knowledge they learned and what drove them to travel rather than, as have been the tradition, concentrating on the role of Linnaeus. The second focal point in this article is the relationship between informers and naturalists in the tradition of Linnaean travelling. Again this is a topic that has also been largely ignored in previous work on Linnaean travelling, at least outside the field of ethnobiology. Here the role of informants will be discussed in the light of discussion of eighteenth-century political economy and how it rendered talking to local people an important part of travelling both inside and outside Sweden, or more precisely in Sierra Leone and what it tells us about knowledge generation. 3 While deliberately ignoring geographical and disciplinary borders traditionally drawn on in older studies of Linnaean travellers and informers this essay does take changes to the geography of late eighteenth-century natural history serious. How, in the wake of social, political and economic changes, travellers and informers contributed to a spatial reconfiguration of natural history which followed Linnaeus’ innovation is a theme that runs through both sections of the essay, as well as one which forms a theme in the third part where I attempt to conclude my discussion. Moving on – travelling and careers in eighteenth-century Europe As Kenneth Nyberg and I have argued elsewhere, to the individual student the journeys of the kind Linnaeus promoted, which included domestic travelling as well long distance transnational trips, were just as much a way of moving on in their education and career as contributing to a global natural history inventory project. Thinking about traveling as an education and career enhancing process does make it possible also to connect up the long distance journeys of the apostles with the natural history excursions Linnaeus organised around Uppsala (Hodacs and Nyberg). In fact Linnaeus’ excursions can be seen as a first stage in an education geared towards sending out naturalists on long distance journeys, the latter marking a form of graduation. Excursions of course have a long tradition within the discipline of natural history. This subject was taught in early modern universities as part of the medicine curriculum. Plants for example provided the raw material for many drugs; to know botany was to know which plants to use and where to find them. Next to botanical gardens the landscapes around the universities formed outdoor class rooms in which particularly the foundations of systematic botany was taught (Hodacs “In the field”). Although Linnaeus was not alone using of the outdoors teaching natural history it was a very important part of his pedagogics. He used the botanical garden in Uppsala as one resource; here his flowerbeds matched the classes in the sexual system. This system was designed to help identify plants drawing on the number of stamens and pistils of plants as well as other features, to allocate a plant a place in one of twenty-four classes. Moreover, Linnaeus extensively used the landscape around Uppsala for teaching; his excursions followed the same eight paths year on year, with different biotopes providing class rooms for botany, zoology and entomology. These Herbationens upsalienses, were very popular with students, not only from the Faculty of Medicine but more generally, sometimes up to half of all the students at the university join in.3 Next to local excursions Linnaeus also argued that his students should undertake regional journeys, doing a form of domestic grand tours. Linnaeus set the example himself by travelling extensively with groups of students. In 1734, he travelled around the county of Dalecarlia together with seven students and in 1741 he brought a similar sized group to the Baltic Islands of Öland and Gotland. Linnaeus’ domestic journeys have been compared to a “travelling seminar” (Eliasson 125). On his first journey taking students along Linnaeus gave each his own areas of responsibility; one was to concentrate on botany, one on mineralogy etc. Each evening observations were noted down in their jointly held travel journal. Linnaeus organised the journey to Gotland and Öland in a similar fashion, commenting that by the end of this trip his students needed hardly any reminder or guidance when making observations of peculiar and useful things (Linné, Linné på Öland 158). Travelling was in other words strongly associated with learning to observe. On longer journeys the outdoors offered opportunities to, as Linnaeus put it, “sharpen and train ones attention”, to make observations which was about separating the rare from the common, while walking over meadows, 3 Some of the students hand written protocols from the excursions have been published in Herbationes upsalienses. For more information see the introduction by Uggla in Idem. See also Linné Botaniska Exkursioner and Hodacs “In the field”. 4 cross ditches and along shorelines.4 The length of the journey determined the type of knowledge transferred. Around Uppsala the excursions gave an opportunity to test the taxonomy taught in the lecture hall and the botanical garden, how to identify plants drawing on the sexual system. Longer journeys offered more opportunities to study a wider range of nature. Whatever type of journey, knowing how to observe was key. It is worth noticing that natural history by all account was easily incorporated into an already existing tradition of private education “on the road”. Educational journeys have a long tradition in Europe, most famously perhaps in the forms of Grand tours. On the continent of Europe travelling generated its own pedagogic genre, apodemics, with its specific methods for enhancing learning along the road using questions and answers, and copious note books (Stagl). In Sweden private education extended far beyond the elite social group we tend to associate with it. For example up to a fifth of Uppsala students in the eighteenth-century were the sons of farmers. In order sustain themselves the students needed to take up positions as private tutors, sometimes leaving the university for years at the time (Lindroth A History 143, 145). This is also true of Linnaeus’ students but with natural history becoming increasingly fashionable they had ample opportunities to reproduce the knowledge they had gained travelling with junior students in Sweden and on the Continent of Europe. In fact, such endeavour offered opportunities to not only making a living teaching but also develop as a scholar. Johan Lindwall and Sven Anders Hedin, two less well known naturalists belonging to Linnaeus’ last generation of students both travelled extensively with the young Carl Bäck, the son of Abraham Bäck (1713-1795), president of Collegium medicum in Stockholm and one of Linnaeus’ closest friends. As the case of young Bäck’s journeys illustrates trips were senior and junior students travelled together could incorporate both more basis lessons, such as learning the identities and scientific names of the most common plants and animals, as well as more advanced ways to explore nature. For example, Bäck’s tutors Johan Lindwall took the opportunity to conduct extensive field studies comparing thousands of living samples of the same species in search for taxonomically significant variations while travelling in the southern parts of Sweden in the summer of 1774. Hedin, on his journey with Bäck in 1775 collected and analysed samples of water from central and northern regions of Sweden. Such an exercise did not only help Lindwall and Hedin to advance as a scholar; knowledge on how to conduced field studies and experiments were also transferred from the senior to the junior naturalist although Bäck’s premature death prevent us from tracing the effects of this education beyond his sixteenth birthday (Hodacs and Nyberg 67-97). Natural history journeys involving Linnaeus’ students and conducted as part of a private education have received relatively little attention although they were by all accounts common. This is also the case with several of the student’s longer domestic solo trips within Sweden. In the latter category we find the journey of Peter Jonas Bergius (1730-1790) to the Baltic Island of Gotland in 1752. Three years earlier, in 1749, Lars Montin (1723-1775) set out to Lappland and Johan Otto Hagström (17161792) to the county of Jämtland, on the border to Norway. In the prologue to his printed travel account Hagström described his journey in the following way: He who has not travelled in distant vast lands, in dark forests, and a wild desert: he who has not mounted mountains permanently covered with snow and ice, can hardly imagining the manifold Linné ”Om nödvändigheten” reprinted in a new translation by Annika Ström, in Hodacs and Nyberg, ch. 8, quote from p 189 (”skärpa och träna sin uppmärksamhet”). 4 5 difficulties and dangers facing a traveller, as he trespasses over lakes and fells, over brooks and rivers, over mountains and valleys, and in all sorts of weather.5 That the travellers themselves saw similarities between the landscapes their domestic journeys passed through and more exotic ones suggest that national borders are somewhat irrelevant when we analyse these journeys, although it is not unlikely Hagström used references to faraway places to increase the status of his own journey and perhaps also distract the reader from his origins; he was actually born in Jämtland. Independently of how the journeys and the landscapes in which they passed through were described, what is beyond doubt is that Linnaeus’ students were not only taught the theoretical foundations of their teacher’s new taxonomy in lecture halls they were also trained in how to apply it outdoors as students, as teachers, and naturalists in the making. Their knowledge of how to scan landscapes in search for novel and rare natural objects or features was embodied. This tacit skill in combination with more or less extensive knowledge of Linnaeus’ universally applicable systems for identifying and describing plants and animals gave at least some of the students a competence to explore landscapes across the globe (Hodacs Linnaeans outdoors). This combination made Linnaeus’ students attractive employees to many different institutions and persons inside and outside Sweden. It is in the light of this I suggest we should understand the long distance travelling of Linnaeus’ students described in the map above. With the exception of France, many of the larger and smaller trading and colonializing powers of Europe employed Linnaean naturalists and equipped them to travel. The Dutch East India Company for example employed Carl Petter Thunberg (1743-1828) who came to succeed Linnaeus in Uppsala after that Linnaeus’ son who first inherited the chair died prematurely. The map outlines Thunberg’s journeys to Japan and back, he was in fact travelling outside Europe for seven years before returning to Sweden in 1779. Johan Peter Falck (1732-1774) explored Russian territory, including present day Kazakstan in the late 1760s and early 1770s on an expedition supported by Catherine II and lead by the German scholar Peter Simon Pallas among others. Pehr Löfling (1729-1756) was employed by Spanish authorities, both in Madrid but also on an expedition exploring the Spanish realms of Latin America in the 1750s. The Royal Danish Expedition to Arabia employed Peter Forsskål (1732-1763) as the naturalist on a venture that left Denmark in 1761. In the second half of the eighteenth century it was however the prospect of service under British flag that lured the largest number of Linnaean travelling students away from Sweden. Daniel Solander (1733-1782) and Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) travelled with Captain Cook on the latter’s first and second expedition circumnavigating the earth and exploring particularly the South Pacific. The natural history of the west coast of Africa, around the area of Sierra Leone, became object of study for Andreas Berlin (1746-1774) and Adam Azelius (1750-1837) in two projects initiated in London, more on them below. How Great Britain came made use of Linnaean trained naturalist becomes even clearer if we zoom in on the movement between Uppsala and London in the second half of the eighteenth-century. Linnaeus’ universal approach to natural history, the ambition to encompass the flora, fauna of the world, made Linnaeus’ students attractive to people like Joseph Banks (17231820), president of the Royal Society and the single most important person in British natural history. Banks employed several Linnaean students to travel the world and to work in his collection and libraries in London. The latter aspect is however not captured on the map above. Take for example 5 Hagström 6-7 (Den som ej rest uti aflägsne ödemarker, uti mörka skogar, och en vild öken: den som ej klifvit up på de med evig snö och is betäckte fiällen, kan knapt föreställa sig de mångafaldiga svårigheter och farligheter öfver siör och fiäll, öfver strömmar och älfvar, öfver berg och dalar, uti allehanda väder, som här en resande förekomma.) 6 Daniel Solander who travelled on Captain Cook’s first expedition (on which also Banks travelled) which set out in 1768; he did not return home to Uppsala after the expedition got back in spite of his special status as one of Linnaeus’ favourite students and a likely heir of the chair. In fact Solander seemed to have made London his long term home long before the journey with Cook, although arriving in 1760 London was originally planned only to be one stop on Solander’s itinerary. Instead he soon established himself as London naturalists; his first employment was as assistance in the newly opened British Museum where Solander soon started organizing the collections to match Linnaeus’ taxonomic systems (Duyker 69). He also took central position in the London world of natural history, providing descriptions and identifications of new species arriving from across the globe drawing on his knowledge of Linnaeus’ work. As one of Solander’s biographers put it he was the “taxonomic oracle” of London (Duyker 276). Returning from the expedition with Cook Solander got even more established on the London natural history scene. Banks employed him as his secretary going over the large collections from the South Pacific and assisting Banks in all things natural history. The remit expanded and further Linnaean naturalists were needed; one who followed suit was Jonas Carlsson Dryander (1748-1810), a nephew of the above mentioned Lappland-traveller Lars Montin. Dryander took up an employment with Banks building up and maintaining Banks’ library as well as offering support in the form of Linnaean taxonomic advice to natural historians working in London (Uggla). Other Linnaean naturalists from Sweden who held down similar jobs were the above mentioned Andreas Berlin and Samuel Törner.6 Another reinforcement of the Linnaean grip over London natural history was the arrival of Linnaeus’ collections of plants and other specimen, books, letters and manuscripts in 1784. It was bought by John Edward Smith (1759-1828), following the death of Linnaeus junior (History of the Linnean collections, and Gardiner and Morris). Although Linnaeus’ collections were kept intact, today forming the foundation for the Linnean Society of London, its re-location reflects a more general development of how the world of scholarship was changing at the end of the eighteenth-century. The Republic of Letter had been very central in Linnaeus’ work; as Bettina Dietz most recently has shown Linnaeus could drew on a network of scholars scattered across Europe, providing him with information and material with which help he could incorporate new and improved descriptions of species (Dietz). By regularly publishing new editions of central work such as Species Plantarum, Systema Naturae and Genera Plantarum Linnaeus created a scholarly order predating the institutionalisation and professionalization of nineteenth-century science. The growing importance of London as a centre for natural history, a process in which Joseph Banks and under him Solander and Dryander were highly instrumental, illustrate the beginning of a shift from one knowledge generating system, the Republic of Letter, to one in which institutions rather than individuals played a central role. London was of course also a centre in an expanding empire and a place to which natural history material easily travelled. Its growing role as a centre for natural history globally was however no doubt assisted by the work of individuals such as Solander and Dryander. Educated in the latest modern taxonomic system they were not only able to provide assistance and guidance, their infrastructure-building work reorganizing collections and libraries to match Linnaeus’ taxonomic principle helped establish the latter’s prominence at the heart of what was in the process of becoming a world centre of natural history. Other circumstances, the fact that Sweden was a small neutral country on the fringe of Europe is likely to have helped the Swedish naturalists too. One can turn this into a point about North European scholarly culture more generally, and how representatives of this culture could slot into on-going Neither has received much scholarly attention. Torner or Törner’s life in London can be studied in his letter to Liljeblad (Torner till Liljeblad, X,G320, Uppsala University Library). On Andreas Berlin see Hamberg. 6 7 exploration projects initiated by most importantly perhaps Britain and Russia. There are as David Arnold has discussed a very prominent Baltic presence, including German scholars, involved in laying the foundation of the British Empire in nineteenth-century South Asia (Arnold). Likewise the same scholarly community was active in the exploration of Asia as Russia started to map its Eastern territory as Maria Nyman most recently discussed focusing on the Swedish case (Nyman). This North European diaspora in the colonial projects of the great power of Europe reflected the relatively high level of education around the Baltic Sea, in German speaking areas and in Scandinavia. It also reflects that both Russia and Britain, or at least England, lacked a university system comprehensive enough to educate sufficient number of individuals to fill positions which required scholarly learning in these expanding empires. Such structural explanation apart, the travellers had agency too; to them travelling formed a phase in a career towards a more secure position whether it be inside or outside Sweden. Reading reflections on the pros and cons of travelling it becomes clear that Linnaeus’ students were conscious about the high risks of early modern long distance travelling. “I see quite plainly the dangers of the journey” Löfling wrote to Abraham Bäck in 1753 before setting out to Latin America, less than three years later he was dead.7 Not everyone died or stayed behind abroad though particularly not in the middle of the eighteenth-century; once back from a long journey the career of the traveller could be enhanced in Sweden too. Journeys generated contacts and career opportunities among the Swedish elite; it helped create short cuts to positions not exclusively in academia but also in medicine, as provincial physicians, or as in the case of Pehr Osbeck (1723-1805) within the Swedish church. Osbeck, the son of a crofter, who travelled on the Swedish East India Company’s ship to Canton and back, ended his days as the Dean of Hasslöv, on the West Coast of Sweden. Underlining the connection between travelling, education and careers, the claim here is not to present a particularly novel thesis. Existing literature on grand tours and the apodemic tradition in Europe explores similar strands. What marks the argument outlined in this essay is the link between excursions and exploration, and between journeys inside and outside Europe. One claim here (previously also made in Hodacs and Nyberg) is that they were overlapping forms of travelling, and that they can be thought of as part of an education and a career strategy. Linnaeus’ students were aware of their unique status as Linnaean scholars, educated and trained to observe, collect, describe and name a global flora and fauna. It was job prospects at home, as well as job opportunities abroad, in London but also elsewhere, that that spurred them on, on their journeys. Moreover, and drawing on my more recent research this way of thinking about the journeys of Linnaeus’ students can help outline the contour of a more general group of travellers, including not only Linnaeus’ students but Baltic scholars more generally. These were individuals who stood with one foot in the Republic of Letters, and another in the scientific explorations associated with the expansion different European powers, particularly perhaps that of the British Empire. In the light of this I suggest we distinguish between the two different ways in which the journeys of Linnaeus’ students effected the circulation of knowledge. Firstly, as has been the tradition, we can think of their journeys as generating observations and material which could be added to a growing body of knowledge which increasingly became coded in Linnaean taxonomy. Secondly, taking into account the changing world of scholarship, and the politics of the European expansion, we can also think about the students as assistants in the building of infrastructure able to contain and communicate the same information. In other words Linnaeus’ students were both knowledge generators and builders of knowledge infrastructures. In either case, what made them travel were their ambitions, 7 Quoted in Hodacs and Nyberg 150 (”Nog ser jag ganska godt resans farlighet”). 8 what enabled them to travel was their education under Linnaeus which provided them with a mix of embodies skills and theoretical knowledge. Informers, naturalists and the circulation of knowledge As the discussion about the growing role of London already indicated above the ways in which circulation and accumulation of natural history knowledge evolved reflect changing political and economic circumstances globally. Britain and London was the centre of an expanding empire and the success of Linnaean natural history was linked to how it could be utilised to promote such expansion. This brings us to another dimension to Linnaeus’ work as well as another point of enquiry namely the relationship between the traveller and the informer and how the economic use of nature informed the circulation of knowledge. Next to the taxonomic system building ambitions Linnaeus also had economic motives behind his exploration of nature. Linnaeus’ natural history was closely linked to mercantilism which stipulated that a state’s economy could only grow by establishing colonies or by taking over trade of other states. Wealth was measured in silver and gold and the amount of valuable metals a state accessed indicated how rich it was. A positive balance of trade, increased export and reduced imports, helped build up the stock of valuable metals. This is also where natural history comes into the picture. By exploring nature at home domestic substitutes for goods which otherwise had to be exported from abroad could be identified. Linnaeus was for example eager to find alternatives to tea which otherwise had to be imported from China. He also tried to bring tea plants from China in order to start cultivation of tea in Sweden. Natural history and natural historians played an important role in both projects although, as Koerner discussed in some details, with little economic success (Koerner). Linnaeus was not alone in promoting home grown and home produced goods over imported in Sweden. A similar understanding laid at the heart of the Swedish Academy of Science founded in 1739, but it was also central to the party that dominated the Swedish politics between the end of the Great Nordic Wars and the 1760s. However, by the second half of the eighteenth-century the discussions in political economy moved on. From France came physiocracy which shifted the focus from trade to agricultural production. This shift coincided with political and cultural changes in Sweden which side-lined natural history and many of its political supporters (Johannisson). While Linnaeus’ taxonomic innovation held ground the loss of political and institutional support helped explain why Britain and London became attractive destination to later generations of Linnaeus’ students as I discussed in the last section. This was something noted by older generations of Swedish naturalists. For example Montin, the Lappland traveller and the uncle of Dryander wrote regularly to Abraham Bäck, Carl Bäck’s father, complaining about the lack opportunities in Sweden for naturalists, and, rightly as it was, fearing his nephew would disappear into Banks’ service, just like Solander.8 As Banks rise to prominence indicates, within a British context natural history had an important role exploring natural resources in areas which were in the process of becoming incorporated into the globally expanding trade system, and as political power followed, the British Empire (Drayton, Gascoigne). Appreciating the limits of Sweden’s power after the end of the Great Nordic War, Linnaeus did not promote expansion abroad. His approach to the domestic landscape of Sweden was however coloured by colonizing ventures of the more expansive European states. Turning is eyes inwards Linnaeus suggested the domestic landscape offered similar opportunities as exotic ones (Koerner). Finding these opportunities involved naturalists informing themselves of what was out 8 See e.g. L. Montin to A. Bäck 3 of April 1778, MS 36.28: 1-17, Hagströmerbiblioteket, Stockholm. 9 there by travelling, by observations of nature but also from talking to local people about how they used nature. These accounts have primarily been used by modern ethno-biologists such as Ingvar Svanberg to whom the information Linnaeus and his students’ generated provide valuable sources on the interaction between humans and nature in the past (Svanberg 13-16). This information does however have a wider scope beyond the information about specific species and their use, it can also tell us something about the relationship between the naturalists and those who informed them, and about knowledge generation more generally in Sweden but also elsewhere. Mikael Bravo has used the term “geographical gift” to discuss the role-play of European geographers engaged in questioning local people they encountered in areas unfamiliar to the Europeans. The gifts were local information about the immediate surroundings, information net yet coded on European maps, and the material gifts offered in return for this information, for example glass pearls, and tools. While this initial exchange reflected an asymmetry, with the Europeans being dependent on advice from local informants, the table was soon turned as such encounters were often the first in a series which more often than not lead to the political and physical subordination of the none-Europeans. In Europe the gift exchange became a troop in writing on these encounters, giving the scientists and their knowledge seeking activities a specific role and protocol in which the indigenous response could slot in. The role and knowledge of the so called native was re-defined in the process, it became part of ethnography, a different form of knowledge to the exact sciences of geography and navigation (Bravo). Looking at Linnaeus’ interaction with local people in Sweden, it is I suggest possible to say that they granted the naturalist what can be called political-economic gifts, involving a somewhat similar set of roles to those identified by Bravo: there are less glass pearls and tools handed out but there is a knowledge hierarchy reinforced and a knowledge protocol in place. For example, in his travel account from the journey to the Baltic islands of Öland and Gotland, Linnaeus wrote: “Peasant-botany is not to scorn at, and the farmers, at least in this country, have their own names for almost all plants. I took a meek farmer with me to the meadow, he was familiar with far more plants than I ever would have guessed.” 9 Such statements needs to be understood in the light of the existing divides between the learned culture Linnaeus represented, and negative connotations associated with some popular knowledge. Moreover, as Steven Shapin has discussed, the epistemological shift associated with Scientific Revolution in seventeenth-century science was deeply embedded in contemporary notions of honour within certain socio-economic groups. The best, that is the most truthful scholars were gentlemen, steeped in chivalry culture and economically independent. Shapin describes how out of this culture grew a system of trust that informed exchanges of observations and statements in the Royal Society (Shapin). Linnaeus was using his status as a scholar to accredit and verify observations but this was also a more complex process in which the naturalist and the informers were ascribed different roles. For example, in a letter to the Uppsala Science Society on returning from his solo trip to the north of Sweden in 1732 Linnaeus writes about an encounter with a woman picking Wolves-bane, Aconitum septentrionale, a poisonous plant traditionally used in the production of insect repellent. Asking her why she picked the plant she responded she was going to eat it. Linnaeus warned her strongly against such endeavour but she indicated that she had ate before and that “…I [Linnaeus] did not understand Linné Öländska p 237 (“Bonde-Botaniken är intet alltid til at förakta, och hafwa Böndren, åtminstone här på Landet, sine egne namn mäst på alla Örter. Jag tog en beskedelig Bonde med mig t på Ängen, som där kiände långt flere Örter än jag någonsin förmodat.) 9 10 what such a good plant could be used for. And if I got of my horse, followed her home, I could see what she meant.” Following a description of how the plant leaves were prepared, and how the woman’s husband, an old woman, and her children to whom “it made a lovely dinner” suffered no sickness or other symptoms Linnaeus congratulates himself for so “boldly seeking out information that reflections alone could not fathom”.10 Against the backdrop of natural history in early modern political economy the gift in this context is information about a new source of food which potentially ultimately benefited the state and all its subjects. In the process of exchanging the gift distinct roles or identities are generated. The women is presented as ignorant but guided by traditions, local knowledge, the naturalists an empiricist who without prejudice uncover new knowledge, coding it in such a way that it could circulate, thereby turning himself into a patriot. The example above suggests, perhaps falsely, a relative uncomplicated process of knowledge circulation and identity generation. A different political economy and geography could produce other identities but also other issues associated with extraction, communication and circulation. Take the example of Adam Afzelius, one of the Swedish naturalists working in a British African context where he was employed by the Sierra Leone Company in the 1790s. The Company was in part a philanthropic anti-slavery project and a commercial enterprise. Afzelius’ objective, as one of the naturalists working for the Company, was to explore the natural resources in Sierra Leone in order to promote future exploitation of the area, ultimately providing an alternative economy to the slave trade which for centuries had provided the West Indies, and South and North America with slaves. Afzelius had been recommended to the company by Joseph Banks but he was not the first Linnaean botanist who spent time on the West Coast of Africa. Another student of Linnaeus, Andreas Berlin, also connected to Joseph Banks, was sent there in 1773 to work exploring the area together with Henry Smeathman (1742-1786) although Berlin died four months into his stay. The Sierra Leone Company was the most viable of a series of British projects that crossed paths on the West Coast of Africa and which form a backdrop to the incorporation of Sierra Leone in the British Empire in the nineteenth-century. A circumstance important for one project was the need to find a replacement to North America as a place to which deport convicted Britons following the American Revolution in 1779. Together with Australia the West Coast of Africa were considered as alternatives, something that also coincided with how race had become a central trope in Britain, particularly in London where deportation plans for Black people living in London gained ground. A group from the Black community together with a group of prostitutes, another “concern” in metropolitan London, were transported to Sierra Leone by the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, later the George Bay Company, in 1787. A second project was the more imminent issue of what to do with the former slaves who had fought on the side of the British in the American War of Independence. Following the British defeat they had been relocated to Nova Scotia on the East Coast of Canada, where they struggled to make a living under dire circumstances. A representative of this group made his way to London to voice his concern at a time when the Evangelicals’ plan with Sierra Leone Company was taking form. A third project related to the Evangelicals was that promoted by Swedenborg groups in Sweden and Britain. The writings of the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) pointed to Central Africa as the place where people of a pure faith with close contacts to the angels who informed Swedenborg’s visions could be found (Coleman). Afzelius was closely connected to the Swedenborg group both in Sweden and in London. He and another Swede, August Nordenskiöld (1754-1792), who worked as a mineralogist for the Sierra Leone Company, saw the establishment of Freetown as an opportunity to establish a foothold in Africa from where they could Quoted from Svanberg p. 232 (“… att jag eij förstodo hwar till en så god ört tienlig woro. Ty stiger jag af hästen, föllier henne hem, att i sielfwa wärket se det som hon förtalde.”) 10 11 travel inland in search for the Africans Swedenborg had had visions about (Ambjörnsson 79-144 and Lindroth “Afzelius”). Afzelius’ additional plans to follow Swedenborg’s lead and locate the Africans of pure faith did not prevent him from doing his job as the Sierra Leone Company’s naturalists. For plants this work involved an examination of living material and a first preliminary allocation of its identity in Linnaeus’s sexual system. Once conserved the specimen could be stored away, either kept by Afzelius or shipped away to London where its identity could be confirmed drawing on other collections and reference material available there.11 This seemingly straight forward process was however quite complex. First of all Afzelius needed to get hold of material to analyse, identify, store and despatch. In order to do so he employed an extensive network of collectors. Afzelius’ heavy reliance on paid local collectors was probably due to several different circumstances. Judging by the journal longer trips were associated with hardship and discomfort; local political circumstances might also have prevented Afzelius. But maybe more importantly, the benefit with using the local collectors was that objects and information of how a plant was used, as food stuff, as a medicine, or in production processes, could passed on to Afzelius together with the local names for plants. This, in theory enabled Afzelius to connect local knowledge with Linnaeus’s universal system for keeping track of flora. Typically perhaps the journal reveals only the first names of Afzelius most regular contributor, a man called Peter identified as a servant by editor of Afzelius’ journal (180). That he was a long standing assistant to Afzelius is revealed in passages where Peter is said to recall collections from a few years earlier, arguing that Afzelius needed to separate old and new samples of plants the naturalist had been inclined to ascribe as belonging to the same species (37). More importantly here, Peter was very active in providing the naturalists with vernacular names in local languages such as Temne and Bullom, and Susu.12 In fact, the diary records several times when the sole topic of Afzelius and Peter’s exchanges were plant names, when Peter “informed” or “gave” Afzelius names (32, 37). The significance of this information is further underlined in Afzelius’ interaction with Peter’s sister, who typically is not named at all. According to the diary she relieved Afzelius from “confusion and wrong naming” of three different plant species, Scoparia dulcis, Cassia rugosa, and Schmidelia racemosa. The process involved matching the right local names, referred to in short hand as “Tim”, “Bull” and “Sus” to the right scientific names, and to the right specimen, identified with a number and a date for when it was collected (39). Afzelius’ recording of Peter’s and his sister’s information as well as other people’s suggest that mapping of local names took more time and effort than the systematic work identifying and describing the plants following the taxonomic principles of Linnaeus. The problem for Afzelius was the transient nature of the community populating Freetown and its surrounding and finding a language in which to communicate. Some of those who sold material to Afzelius were members of the group of settlers who had come from Nova Scotia and who consequently had little to provide in terms of local names although they of course spoke English (20). Those who knew the local names and traditional of use of plants and other material, people who Afzelius typically referred to as “Native”, did by all account not speak English and could only provide Afzelius with fragments of information (16, 17). See particularly Appendix, ”Index to my journal, Travels & Descriptions” in Afzelius 170-174 for a good illustration the work process. 12 On the regions different languages and Afzelius negotiated them, see Introduction by Alexander Peter Kup in Afzelius 4-7. 11 12 Only rarely did Afzelius meet someone who had both the knowledge and the language with which to communicate with him. One such person however was the informer “Calamina”, better known as Miss Betsy Herd. According to Bruce Moser, who traced her in numerous records, Heard was the daughter of a British slave trader and local women born 1759. It was quite common that local dignitaries established links with European traders by sending them daughters born to slave women in their household although it is not possible to establish that Heard’s mother was a slave. As an adolescent and together with other Eurafrican children of similar origin, most of them boys, Heard was sent to England for an education. Such schooling reflected not only on the ambitions of the parents but also an interest among British merchant houses with strong links to the slave trade on the West Coast. An English education helped forged relationships that could be drawn on later on, after the students had returned to Africa. Returning to Bereira, what is now Republic of Guinea, Miss Heard also took over her father’s business. She owned ships and the main wharf in Bereira, trading in more general goods as well as slaves. Her trade and position was not the only source of her influence. Heard is known for her role in the first decade of the nineteenth-century helping the English to negotiate with Mandinea and Susu chiefs on their support to enemies of Freetown (Mouser 321-325). Heard’s position as a “culture-broker” (321) illuminates the complex reality of life and politics in the contact zone. Moser suggests that Heard’s progress towards a position of influence reflects on her outside position, it was a way to compensate for the absence of local family ties (334). Miss Heard does however seemed to have had a strong connection to the local landscape, the plants it hosted and how they were used. Moreover, she was by all account fluent in English and educated in such a way she was able to act go-between between the European naturalists and local people and their practices. The anticipation of the imminent visit of Miss Heard to Freetown in January 1796 indicate both what prominent and well known person she was and on her status as someone familiar with the local natural history. Judging by his journal both Afzelius and Freetown’s Doctor Thomas Winterbottom,13 were keen to meet Heard (Afzelius 43, 46). And for good reasons, Heard’s two day stay in Freetown involved an excursion undertaken together with Afzelius, Winterbottom, and an “old respectable women” referred to as “Nammonammodu’s sister”. Together the company explored the area between two brooks and collected a “number of plants” which they then brought back to Freetown. Examining the plants in the “Doctor’s room”. Afzelius describe Miss Heard as “showing her skill and knowledge of Africa’s Medical Plants and at the same time her politeness to us in telling us without reserve the medical uses of the following plants.” (52). In fact, judging by Afzelius’ diary Heard had so much to say it was hard to note it all down. The first of twenty-one descriptions of medical concoctions and medical uses of specific plants, a remedy against fevers and belly pain, included no less that eleven different plants; too many because “for want of attention” Afzelius was only able to identify three of them (52). In the “Index to my Journals, Travels & Descriptions” where Afzelius converted and condensed the results of his botanical work in Sierra Leone using the twenty-four classes of the sexual system as the organizing structure, these and other communication and everyday problems are however erased (170174). Instead this narrative has been replaced by an order suggested not only by the taxonomic structure of the index but also by how the single entries are written. Here the scientific binominal names are followed by the local names listed on the left hand side column, and references to the diary and other note books containing descriptions of the plants, dates of observations and collections, 13 On the relationship between Winterbottom and Afzelius see Afzelius, Notes, Part 1 (note 1) pp. 78-79. 13 geographical references, information on traditional uses, and names of informers on the right. This structure does not only create a distance between the naturalist and the informer, it suggest that the informer was subordinated the naturalists rather than the latter being dependent on the former. Moreover, it is a summary that do not at all records the local circumstances directing the work, the transient character of the Freetown population or its location in a politically contested zone. The status and background of Afzelius’ arguably most important informer, Miss Heard, is not recorded in the index or the diary either. Her ambiguous position, as someone with local knowledge and ability to communicate this knowledge who could contribute towards finding alternative resources to the slave trade, and, as someone who was part of the slave trade economy the Sierra Leone Company was aiming to replace, is not captured in Afzelius writing on Sierra Leone. Afzelius’s work and particularly his index are of course symptomatic how a Linnaean scholar worked, for the need to fragment knowledge in order to fit it into a system that could travel and be circulated. However it is not, as the discussion above illustrates, symptomatic for what happened on the field, how important informers was and how complicated the communication was. Such a conclusion can form the basis for a critique of for example Mary Louise Pratt’s discussion of another Linnaean scholar’s relationship to the African landscape, namely that of Anders Sparrman, one of Captain Cook’s companions who had travelled in Africa twenty years or so earlier than Afzelius. Pratt writes about Sparrman’s relationship to the South African landscape in the following way: “The landscape is written as an uninhabited, unpossessed, unhistoricized, unoccupied even by the travellers themselves. The activity of describing geography and identifying flora and fauna structures an asocial narrative in which the human presence, European or African, is absolutely marginal, though it was, of course, a constant and essential aspect of the traveling itself. In the writing, people seem to disappear from the garden as Adam approaches – which, of course, is why he can walk around as he pleases and name things after himself and his friends back home.”(Pratt 51-52). In defence of Pratt it is worth highlighting that she is referring to Sparrman’s printed travel account while I have used Afzelius’ diary, very likely never intended to be published at least not without heavy editing, a process which was likely to minimise the importance of informants, helpers, cotravellers. Nonetheless to stipulate that the Linnaean gaze was one which failed to take notice of local people is failing to realise the role of popular knowledge and ultimately political economy in Linnaean natural history and in the exploring of landscapes both inside and outside Europe. There are of course important differences between what happened in Sweden and in Sierra Leone. Linnaeus’ domestic natural history explorations were part of a project that was ultimately patriotic, where those he interviewed in Sweden also were subjects of the same state as Linnaeus. Afzelius in contrast was working on behalf of a company, and ultimately towards an exploitation of West Africa, as part of an emerging colonial economy. It is also notable that pending on who Afzelius corresponds with on issues to do with his work in Africa his role and identity can vary. Sometimes he defines his work as an expression for his love for science making him a virtuous member of the European community of scholar which together made up the Republic of Letters, sometimes however he also presents himself as an entrepreneur, or a Projector in natural history, and sometimes he does both. Writing to his brother Pehr Afzelius (1760-1843) about a new medicinal “A bark equal to the Peruvian in its efficacy, but superior to it in other respects”, “an indelible Blue, “a fine Elastic Gum” he had found around Freetown Adam Afzelius concludes that he hoped his finds “will turn useful to 14 mankind & even to my countrymen if they choose it, for I must be paid according to the dangers I have seen in acquiring the knowledge of these things. Don’t you think it is fair?14 There is no evidence Afzeliuz benefitted in an economic sense from his travelling: he received no promotion in Uppsala on his return. Much to his frustration waiting for him was the same position, as Demonstrator at the Botanical Garden he had left ten years earlier. Bemoaning his lack of recognition Afzelius wrote to a friend comparing his situation to that of the Scottish explorer Mungo Park (17711806).15 Park had travelled on behalf of the African Association, another organisation Banks was engaged in, exploring the course of the Niger River, present day Senegal, in the 1790s; a journey that made him famous not at least due to the account he published in 1799 entitled Travels in the Interior District of Africa. However, even if Afzelius had travelled as far as Mungo Park, and published extensively about it, it is not obvious he would have gained a similar status as Park. Afzelius was not British hence unable to draw on patriotic-nationalistic sentiments in Britain and connected up to the expansion of the British Empire. Meanwhile in Sweden there was little political interest for colonial ventures in Africa, or projects of the kind Linnaeus had been so keen to promote, drawing on domestic resources and knowledge. There is a further dimension here which also has to do with audience and readership. Linnaeus published extensively in Swedish. This was part of a plan to diffuse knowledge in Sweden with the aim to promote Swedish production and ultimately the Swedish economy. The fact that the Royal Academy of Science in Stockholm published its proceedings in the native tongue part of the same scheme (Lindroth Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakademins historia 217-376). This might come across as idealistic but it is worth underlining that the Swedish public was to high degree literate, reflecting the strong grip of the Swedish church on popular education. It also means that Linnaeus’ Swedish informants also were potential readers. Afzelius’ informants in contrast were too much smaller extent members of a potential audience; expect Miss Heard most of them were separated by linguistic barriers and different traditions of transferring knowledge. The little Afzelius published on Sierra Leone natural history, was exclusively written for a pan-European readership, a late enlightenment Republic of Letter fused with an audience interested in colonial endeavours. Conclusion Linnaeus’ taxonomic innovations were central for increasing the circulation of knowledge, they provided a system with which the natural history of the world could be coded and communicated. This essay has been concerned with how this happened focusing on the role of travellers and the relationship between travellers and informers in Linnaean natural history. The first part of the essay looked at the agency of Linnaeus’ students and how travelling provided a way forth in complex world of eighteenth century scholarship and society. Learning natural history from Linnaeus meant not only learning taxonomic principles, scientific names and descriptions but also how to observe; how to scan a landscape in order to separate well known plants from new and rare ones. This was a form of embodied knowledge which was gained outside on the field, on excursions around Uppsala and journeys to different provinces of Sweden. As the students moved across the landscape they processed nature, generating knowledge that could be circulated in letters and publications far beyond the local in which it originated. The journeys of the students did also work as a form of graduation and social promotion. Travelling turned students into scholars and it 14 15 A. Afzelius to J. Afzelius 28th of Feb 1797 G2C, Uppsala Universitetsbibliotek. Afzelius to Silverhielm, 20th of November 1801, Ep S 15, Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm. 15 open doors to new positions and careers. In other words there is a social history behind the diffusion of natural history knowledge coded in Linnaean taxonomy, and the Linnaean taxonomy in itself. The second part of the essay studied at the relationship between travellers and informers against the backdrop of the role of natural history in early modern political economy. Travellers and informers were in possession of specific skills and information somewhat unique to them, either in the form of an education in Linnaean taxonomy, particularly true in respect to Linnaeus’ first generations of students, or an intimate knowledge of local plants, animals and minerals, how they were used and what they were called. Combining the knowledge of the Linnaean traveller and the local informer was however by all account a complex process which involved the development of a set of identities, generated by the naturalists writing. The example from the Swedish context suggest that while this identity construction took place against a backdrop of early modern European scholarly culture, which helped establish the higher status of the naturalists in an epistemological sense, other aspects helped bring the informer and naturalists more in line with one another. They shared a language and a possibly also a rudimentary form of public culture that surrounded Swedish natural history. Moreover, they were both subjects of the same state, a state which also central in the shaping the naturalist’s identity, as a patriot. The transient and multi-language environments of Freetown in contrast restricted the relationship and the exchange between the Linnaean naturalists and the informer. English was one of the few means by which local knowledge could be linked to universal knowledge systems but this language link also help underline the legacy of the contacts between the West Coast of Africa and Europe, particularly within the tradition of slave trade. The backdrop of the Atlantic long distance trade could turn the naturalists into a projector, while the identities of informers were reduced to a first name, to “Peter” or “Peter’s sister”, “a Native”, or, as the example of Miss Heard illustrates, someone with language skills and local knowledge only. The latter’s English education and her links to Eurafrican slave trading fails to make to the records of Afzelius. Following the Linnaean travellers and their work also help reveal how the circulation of knowledge was reconfigured spatially over time. One increasingly important node in eighteenth-century natural history was London, the host of a growing number of collections of natural history material and the home to a string of students of Linnaeus. Their arrival reflects both the declining status of natural history in Sweden and the growing need for naturalists in Britain and the British Empire. Their legacy is reflected in their work in central London collections; the classes of Linnaeus sexual system formed the back bone in Joseph Banks botanical library, carefully catalogued by Jonas Carlsson Dryander. The same system guided Daniel Solander’s reform of the catalogues of newly established British Museum. This was system building work of a material and administrative type which enabled London to host the ever growing numbers of specimen and publications that arrived from across the world, including Afzelius’ collections from the West Coast of Africa and those generated by Linnaeus in Uppsala. The journey of the latter in 1784, the collection was sold by Linnaeus’ surviving family to the English botanist John Edward Smith, is perhaps the starkest sign of how the circulation of knowledge was changing in a spatial sense. Located at the heart an expanding Empire London had replaced Uppsala and other earlier centres of learning which were unable to host, maintain and expand collections aspiring to be global and universal in reach and character. As such it reflects on the end of the Republic of Letters, to whom the network of naturalists who had provided Linnaeus with material and input had belonged, and the advancement of a new form of institutional based organisation of knowledge. Such a backdrop does also help illuminate Afzelius’ struggle making his way in the world as a naturalists, not only did the complex social and political world of Sierra Leone hamper his collection work, he also had to negotiate two different knowledge circulating system, one old one in 16 which the Republic of Letter and Sweden were significant reference points, and one new one where London and Empire formed the focal point. Bibliography Ambjörnsson, Ronny. Det okända landet: tre studier om svenska utopister. Stockholm: Gidlund, 1981. Afzelius, Adam. Sierra Leone journal 1795-1796. Ed. Alexander Peter Kup and Carl Gösta Widstrand. Uppsala: Inst. för allm. och jämförande etnografi, 1967. Blunt, Wilfrid, Carl von Linné. Linnaeus: the compleat naturalist. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2001. Bravo, Michael T. ”Ethnographic Navigation and the Geographical Gift.” Geography and Enlightenment, Ed. David N. Livingstone and Charles Withers. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999. Carlyle, E. I. “Winterbottom, Thomas Masterman (1766–1859)”, rev. Patrick Wallis, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. 12 April 2014 http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29772. Coleman, Deirdre. Romantic colonization and British anti-slavery. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. David, Arnold. “Plant Capitalism and Company Science: The Indian Career of Nathaniel Wallich.” Modern Asian Studies, 42.5 (2008): 899-928. Dietz, Betina. “Contribution and Co-operation: The Collaborative Culture of Linnaean Botany,” Annals of Science. 69.4 (2012): 551-569. Drayton, Richard H. Nature's government: science, imperial Britain, and the 'improvement' of the World. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000. Duyker, Edward. Nature's argonaut: Daniel Solander, 1733-1782: naturalist and voyager with Cook and Banks. Melbourne: Miegunyah Press, 1998. Eliasson, Pär. Platsens blick. Vetenskapsakademien och den naturalhistoriska resan 1790– 1840. Umeå: Institutionen för historiska studier, 1999. Fries, Theodor Magnus. Linné: lefnadsteckning. Stockholm: Fahlcrantz, 1903. “History of the Linnean collections, prepared for the Centenary Anniversary of the Linnean Society,” Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, (1887-88): 18-34. Gardiner, Brian and Mary Morris. “The Linnaean collections.” The Linnean Special, Issue 7. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. Gascoigne, John. Science in the service of empire: Joseph Banks, the British state and the uses of science in the age of revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Herbationes upsalienses. Protokoll över Linnés exkursioner i Uppsalatrakten. 1, Herbationerna 1747. Red och med noter försedda av Åke Berg. Med en inledning av Arvid Hj Uggla, Uppsala 1952. 17 Hagström, Johan Otto. Jemtlands oeconomiska beskrifning eller Känning i akt tagen på en resa om sommaren 1749, Stockholm 1751. Hamberg, Erik. ”Anders Berlin - en linnean i Västafrika.” Svenska Linnésällskapets årsskrift. (1994/1995): 99-108. Hodacs, Hanna. ”Linnaeans outdoors: the transformative role of studying nature ‘on the move’ and outside.” The British Journal for the History of Science. 44.2 ( 2011): 183-209 Hodacs, Hanna. “In the field: exploring Nature with Carolus Linnaeus.” Endeavour 34.2 (2010): 4549. Hodacs, Hanna , and Kenneth Nyberg. Naturalhistoria på resande fot: om att forska, undervisa och göra karriär i 1700-talets Sverige, Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2007. Johannisson, Karin, ”Naturvetenskap på reträtt. En diskussion om naturvetenskapens status under svenskt 1700-tal.” Lychnos (1979–1980): 107-154. Koerner, Lisbet, Linnaeus: nature and nation. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999. Lindroth, Sten. A History of Uppsala University 1477–1977. Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet, 1976. Lindroth, Sten. “Adam Afzelius, en linnean i England och Sierra Leone.” Lychnos (1944-45): 1-54, Lindroth, Sten. Kungl. Svenska vetenskapsakademiens historia 1739–1818 I–II, Band I:I Tiden intil Warwntins död (1783). Stockholm, 1967. Linné, Carl von, Botaniska Exkursioner i trakten av Uppsala. Avhandling framlagd i Uppsala 1753, respondent A. N. Fornander. Valda avhandlingar av Carl von Linné i översättning utgivna av Svenska Linné-Sällskapet Nr 1, Uppsala [1753] 1998. Linné, Carl von. Öländska och Gothländska Resa, Stocholm and Uppsala, 1745, Linné, Carl von. Linné på Öland. Utdrag ur Carl Linnaeus’ dagboksmanuskript från öländska resan 1741, ur den publicerade reseberättelsen, andra tryckta arbeten, avhandlingar, brev m.m. Ed. Bertil Gullander, Stockholm: Nordstedt, 1970. Linné, Carl von. ”Om nödvändigheten av forskningsresor inom fäderneslandet”. Tal vid tillträdandet av professuren i medicin, hållet i Uppsala den 17 oktober 1741. [Originalets titel: Oratio qua peregrinationum intra patriam asseritur necessitas, Uppsala 1741.] Translation by Annika Ström, reprinted in ch. 8 in Hodacs and Nyberg. Mouser, L. Bruce. “Women Slavers of Guinea-Conakry.” Women and slavery in Africa. Ed. Claire C. Robertson, and Martin A. Klein. Madison, Wid. University of Wisconsin Press, 1997. Müller-Wille, Staffan. “Walnuts at Hudson Bay, Coral Reefs in Gotland: The Colonialism of Linnaean Botany.” Colonial botany: science, commerce, and politics in the early modern world, Ed. Londa L. Schiebinger, and Claudia Swan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005. 3448. Müller-Wille, Staffan, and Isabelle Charmantier. “Natural History and Information Overload: The Case of Linnaeus.” Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C 43.1(2012): 4-15. Nyman, Maria. Resandets gränser: svenska resenärers skildringar av Ryssland under 1700-talet, Södertörns högskola, Diss. Lund: Lunds Universitet, 2013. 18 Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial eyes: travel writing and transculturation. London: Routledge, 1992. Shapin, Steven. A social history of truth: civility and science in seventeenth-century England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994. Stagl, Justin. A History of Curiosity. The Theory of Travel 1550–1800. Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1995. Uggla, Arvid Hj. ”Jonas Carlsson Dryander.” Svenskt Biografiskt Lexikon, Vol. 11 (1945):468-472. Wallström, Tord. Svenska Upptäckare, Höganäs: Bra Böcker, 1982.