Cell death

advertisement

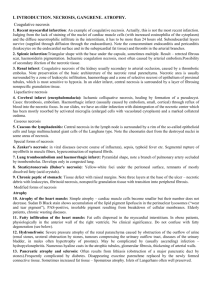

Normal cells that are subject to a damaging stimulus may become sublethally damaged. If the stimulus abates, cells recover but if it continues, cells die and undergo necrosis. Massively damaging stimuli, e.g. great heat or strong acids, cause immediate death of cells without any sublethal damage. Certain special stimuli can cause pathological cell death by switching on apoptosis (see Cell death, • is one of the most crucial events in the evolution of disease of any tissue or organ. Causes of cell injury • External causes – gross physical violence of an automobile accident to • internal endogenous causes, – a subtle genetic mutation causing lack of a vital enzyme that impairs normal metabolic function. Physical Agents. • Prick of a thorn • mechanical trauma, • extremes of temperature (burns and deep cold), • sudden changes in atmospheric pressure, • radiation, • electric shock Chemical Agents and Drugs • Simple chemicals such as glucose or salt in hypertonic concentrations may cause cell injury directly or by deranging electrolyte balance • Even oxygen, in high concentrations, is severely toxic. • Trace amounts of agents known as poisons, such as arsenic, cyanide, or mercuric salts, may destroy sufficient numbers of cells within minutes to hours to cause death. Chemical Agents and Drugs • environmental and air pollutants, • insecticides, and herbicides; • industrial and occupational hazards, such as carbon monoxide and asbestos; • social stimuli, such as alcohol and narcotic drugs; • variety of therapeutic drugs. Infectious Agents. • viruses • tapeworms. rickettsiae, • bacteria, • fungi, Immunologic Reactions. • immune system serves an essential function in defense against infectious pathogens, • immune reactions may, in fact, cause cell injury. – The anaphylactic reaction to a foreign protein or a drug is a prime example, – reactions to endogenous self-antigens are responsible for a number of autoimmune disease Oxygen Deprivation. • Hypoxia is a deficiency of oxygen, which causes cell injury by reducing aerobic oxidative respiration. • Hypoxia is an extremely important and common cause of cell injury and cell death. hypoxia is inadequate oxygenation • cardiorespiratory failure. • Loss of the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, as in anemia or • carbon monoxide poisoning (producing a stable carbon monoxyhemoglobin that blocks oxygen carriage), • Depending on the severity of the hypoxic state, cells may adapt, undergo injury, or die. – if the femoral artery is narrowed, the skeletal muscle cells of the leg may shrink in size (atrophy). – a balance between metabolic needs and the available oxygen supply may be achieved. More severe hypoxia induces injury and cell death. • ischemia • loss of blood supply from impeded arterial flow or reduced venous drainage in a tissue. • Ischemia compromises the supply not only of oxygen, but also of metabolic substrates, including glucose (normally provided by flowing blood). • ischemic tissues are injured more rapidly and severely than are hypoxic tissues. Genetic Derangements. • genetic injury may result in a defect as severe as the congenital malformations associated with Down syndrome, caused by a chromosomal abnormality, • subtle as the decreased life of red blood cells caused by a single amino acid substitution in hemoglobin S in sickle cell anemia. – Variations in the genetic makeup can also influence the susceptibility of cells to injury by chemicals and other environmental insults. Nutritional Imbalances. • Protein-calorie deficiencies • Deficiencies of specific vitamins • Nutritional problems can be self-imposed – as in anorexia nervosa or – self-induced starvation. • nutritional excesses have also become important causes of cell injury. • Nutritional Imbalances. • Excesses of lipids predispose to atherosclerosis, • obesity is a manifestation of the overloading of some cells in the body with fats. • In addition to the problems of under nutrition and over nutrition, the composition of the diet makes a significant contribution to a number of diseases. • Metabolic diseases such as diabetes also cause severe cell injury. Reversible injury • generalized swelling of the cell and its organelles; • blebbing of the plasma membrane; • detachment of ribosomes from the endoplasmic reticulum; • and clumping of nuclear chromatin. • Laminated structures (myelin figures) derived from damaged membranes of organelles and the plasma membrane appear irreversible injury • • • • increasing swelling of the cell; disruption of cellular membranes; swelling and disruption of lysosomes; presence of large amorphous densities in swollen mitochondria; • and profound nuclear changes. – The latter include nuclear codensation (pyknosis), – followed by fragmentation (karyorrhexis) – and dissolution of the nucleus (karyolysis). • Laminated structures (myelin figures) become more pronounced in irreversibly damaged cells. Proverb of this week There are two principal patterns of cell death, necrosis and apoptosis. cell death the morphological pattern of which is called necrosis occurs after such abnormal stresses as ischemia and chemical injury, and it is always pathological. Apoptosis occurs when a cell dies through activation of an internally controlled suicide program. Physiological • It is designed to eliminate unwanted cells during embryogenesis • and in various physiologic processes, such as involution of hormone-responsive tissues upon withdrawal of the hormone. Pathological apoptosis • Immunological injuries 9 The sequential ultrastructural changes seen in necrosis (left) and apoptosis (right). In apoptosis, the initial changes consist of nuclear chromatin condensation and fragmentation, followed by cytoplasmic budding and phagocytosis of the extruded apoptotic bodies. Feature Necrosis Apoptosis Cell size Enlarged (swelling) Reduced (shrinkage) Nucleus Pyknosis → karyorrhexis → karyolysis Fragmentation into nucleosome size fragments Table 1-2. Features of Necrosis and Apoptosis Plasma membrane Disrupted Intact; altered structure, especially orientation of lipids Cellular contents Enzymatic digestion; may leak out of cell Intact; may be released in apoptotic bodies Adjacent inflammation Frequent No Physiologic or pathologic role Invariably pathologic (culmination of irreversible cell injury) Often physiologic, means of eliminating unwanted cells; may be pathologic after some forms of cell injury, especially DNA damage Mechanism of injury • The cellular response to injurious stimuli depends on – the type of injury, – its duration, and – its severity • depend on – – – the type, state, and adaptability of the injured cell. The cell's nutritional and hormonal status and its metabolic needs. Mechanism of injury How vulnerable is a cell, for example, to loss of blood supply and hypoxia? The striated muscle cell is less vulnerable to deprivation of its blood supply; not so the striated muscle of the heart. Exposure of two individuals to identical concentrations of a toxin, such as carbon tetrachloride, may produce no effect in one and cell death in the other. This may be due to genetic variations affecting the amount and activity of hepatic enzymes that convert carbon tetrachloride to toxic byproducts targets of injury • aerobic respiration involving mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and production of ATP; • the integrity of cell membranes, on which the ionic and osmotic homeostasis of the cell and its organelles depends; • protein synthesis; • the integrity of the genetic apparatus of the cell Cellular and biochemical sites of damage in cell injury Mechanism of injury • DEPLETION OF ATP • MITOCHONDRIAL DAMAGE • INFLUX OF CALCIUM AND LOSS OF CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS • ACCUMULATION OF OXYGENDERIVED FREE RADICALS (OXIDATIVE STRESS) • DEFECTS IN MEMBRANE PERMEABILITY DEPLETION OF ATP Functional and morphologic consequences of decreased intracellular ATP during cell injury. INFLUX OF CALCIUM AND LOSS OF CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS INFLUX OF INTRACELLULAR CALCIUM AND LOSS OF CALCIUM HOMEOSTASIS Sources and consequences of increased cytosolic calcium in cell injury. ATP, adenosine triphosphate. ACCUMULATION OF OXYGEN-DERIVED FREE RADICALS (OXIDATIVE STRESS) Reversible vs. irreversible cell injury • there are clearly many ways to injure a cell, • the "point of no return," at which irreversible damage has occurred, is still largely undetermined; • thus, we have no precise cut-off point • dissolution of the injured cell is characteristic of necrosis, one of the recognized patterns of cell death. • There is also widespread leakage of potentially destructive cellular enzymes into the extracellular space, with damage to adjacent tissues Reversible vs. irreversible cell injury • leakage of intracellular proteins across the degraded cell membrane into the peripheral circulation provides a means of detecting tissue-specific cellular injury and death using blood serum samples. – Cardiac muscle, for example, contains a specific isoform of the enzyme creatine kinase and of the contractile protein troponin; – liver (and specifically bile duct epithelium) contains a temperature-resistant isoenzyme of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase; – and hepatocytes contain transaminases. – Irreversible injury and cell death in these tissues are consequently reflected in increased levels of such proteins in the blood. Nuclear changes in necrosis Necrosis • Necrosis refers to a spectrum of morphologic changes that follow cell death in living tissue, • resulting from the progressive degradative action of enzymes on the lethally injured cell (cells placed immediately in fixative are dead but not necrotic • Necrotic cells are unable to maintain membrane integrity and their contents often leak out. • This may elicit inflammation in the surrounding tissue. Necrosis • The morphologic appearance of necrosis is the result of – denaturation of intracellular proteins and – enzymatic digestion of the cell. • The enzymes are derived either from the lysosomes of the dead cells themselves, in which case the enzymatic digestion is referred to as autolysis, • or from the lysosomes of immigrant leukocytes, during inflammatory reactions. • These processes require hours to develop, and so there would be no detectable changes in cells , for example, a myocardial infarct caused sudden death. • The only telling evidence might be occlusion of a coronary artery. • The earliest histologic evidence of myocardial necrosis does not become manifest until 4 to 12 hours later, • but cardiac-specific enzymes and proteins that are released from necrotic muscle can be detected in the blood as early as 2 hours after myocardial cell death. Necrosis • Necrotic cells show increased eosinophilia – Loss of ribosomes responsible for the of the normal basophilia imparted by the RNA in the cytoplasm – increased binding of eosin to denatured intracytoplasmic proteins • The necrotic cell may have a more glassy homogeneous appearance than that of normal cells, – mainly as a result of the loss of glycogen particles. • the cytoplasm becomes vacuolated and appears motheaten. – enzymes have digested the cytoplasmic organelles, • Finally, calcification of the dead cells may occur. Necrosis • myelin figures – Dead cells may ultimately be replaced by large, whorled phospholipid masses • These phospholipid precipitates are then either phagocytosed by other cells or further degraded into fatty acids; • calcification of such fatty acid residues results in the generation of calcium soaps. Necrosis • Nuclear changes appear in the form of one of three patterns, – due to nonspecific breakdown of DNA • A pattern (also seen in apoptotic cell death) is pyknosis, characterized by nuclear shrinkage and increased basophilia. • A pattern, known as karyorrhexis, the pyknotic or partially pyknotic nucleus undergoes fragmentation. • A pattern The basophilia of the chromatin may fade (karyolysis), a change that presumably reflects DNase activity. • With the passage of time (a day or two), the nucleus in the necrotic cell totally disappears. Once the necrotic cells have undergone the early alterations, the mass of necrotic cells may have several morphologic patterns. Necrosis • . coagulative necrosis When denaturation is the primary pattern • liquefactive necrosis • dominant enzyme digestion, • caseous necrosis • fat necrosis – in special circumstances, Coagulative necrosis • preservation of the basic outline of the coagulated cell for a span of at least some days • The affected tissues exhibit a firm texture. • the injury or the subsequent increasing intracellular acidosis has denatured not only structural proteins but also enzymes • Blocking of the proteolysis of the cell. Coagulative necrosis • The heart is an excellent example – acidophilic, coagulated, anucleate cells may persist for weeks. – the necrotic myocardial cells are removed by fragmentation and phagocytosis of the cellular debris – scavenger leukocytes and by the action of proteolytic lysosomal enzymes brought in by the immigrant white cells. • The process of coagulative necrosis, with preservation of the general tissue architecture, is characteristic of hypoxic death of cells in all tissues except the brain Micrograph shows a section of liver damaged by the poison paraquat. Normal liver cells contrast with injured cells, which are swollen, pale and vacuolated. The normal Cells cell cytoplasm is pink with a a decrease of purple, the purple coloration (basophilia) being due to ribosomes, mainly on the RER Damaged cells . With swelling of ER, ribosomes become detached and reduced in number, so the normal purple cytoplasmic tint is reduced. • Apoptosis is a more orderly process of cell death in which there is individual cell necrosis, not necrosis of large numbers of cells. liver cells are dying individually (arrows) from injury by viral hepatitis. The cells are pink and without nuclei. • Here is myocardium in which the cells are dying. The nuclei of the myocardial fibers are being lost. The cytoplasm is losing its structure, because no well-defined cross-striations are seen. • This is an example of coagulative necrosis. This is the typical pattern with ischemia and infarction (loss of blood supply and resultant tissue anoxia). Here, there is a wedge-shaped pale area of coagulative necrosis (infarction) in the renal cortex of the kidney. • Microscopically, the renal cortex has undergone anoxic injury at the left so that the cells appear pale and ghost-like. There is a hemorrhagic zone in the middle where the cells are dying or have not quite died, and then normal renal parenchyma at the far right. This is an example of coagulative necrosis Figure 1-19 Coagulative. A, Kidney infarct exhibiting coagulative necrosis, with loss of nuclei and clumping of cytoplasm but with preservation of basic outlines of glomerular and tubular architecture. Two large infarctions (areas of coagulative necrosis) are seen in this sectioned spleen. etiology of coagulative necrosis is usually vascular with loss of blood supply, the infarct occurs in a vascular distribution. Thus, infarcts are often wedge-shaped with a base on the organ capsule. Cell Injury • The contrast between normal adrenal cortex and the small pale infarct is good. The area just under the capsule is spared because of blood supply from capsular arterial branches. This is an odd place for an infarct, but it illustrates the shape and appearance of an ischemic (pale) infarct well Liquefactive necrosis • is characteristic of focal bacterial or, occasionally, fungal infections, because microbes stimulate the accumulation of inflammatory cells • For obscure reasons, hypoxic death of cells within the central nervous system often evokes liquefactive necrosis. • Whatever the pathogenesis, liquefaction completely digests the dead cells. • The end result is transformation of the tissue into a liquid viscous mass. • If the process was initiated by acute inflammation the material is frequently creamy yellow because of the presence of dead white cells and is called pus. A focus of liquefactive necrosis in the kidney caused by fungal infection. T he focus is filled with white cells and cellular debris, creating a renal abscess that obliterates the normal architecture. liquefactive necrosis in the kidney caused by fungal infection. The focus is filled with white cells and cellular debris, creating a renal abscess that obliterates the normal architecture. • The liver shows a small abscess here filled with many neutrophils. This abscess is an example of liquefactive necrosis. • Grossly, the cerebral infarction at the upper left here demonstrates liquefactive necrosis. Eventually, the removal of the dead tissue leaves behind a cavity. • As this infarct in the brain is organizing and being resolved, the liquefactive necrosis leads to resolution with cystic spaces. • This is liquefactive necrosis in the brain in a patient who suffered a "stroke" with focal loss of blood supply to a portion of cerebrum. This type of infarction is marked by loss of neurons and neuroglial cells and the formation of a clear space at the center left. gangrenous necrosis • It is usually applied to a limb, generally the lower leg, that has lost its blood supply and has undergone coagulative necrosis. • • This is gangrene, or necrosis of many tissues in a body part. In this case, the toes were involved in a frostbite injury. This is an example of "dry" gangrene in which there is mainly coagulative necrosis from the anoxic injury. wet gangrene). • When bacterial infection is superimposed, coagulative necrosis is modified by the liquefactive action of the bacteria and the attracted leukocytes • This is gangrene of the lower extremity. In this case the term "wet" gangrene is more applicable because of the liquefactive component from superimposed infection in addition to the coagulative necrosis from loss of blood supply. This patient had diabetes mellitus. Caseous necrosis • a distinctive form of coagulative necrosis, encountered most often in foci of tuberculous infection • caseous is derived from the cheesy white gross appearance of the area of necrosis A tuberculous lung with a large area of caseous necrosis. The caseous debris is yellowwhite and cheesy. • This is the gross appearance of caseous necrosis in a hilar lymp node infected with tuberculosis. The node has a cheesy tan to white appearance. Caseous necrosis is really just a combination of coagulative and liquefactive necrosis that is most characteristic of granulomatous inflammation. • This is more extensive caseous necrosis, with confluent cheesy tan granulomas in the upper portion of this lung in a patient with tuberculosis. The tissue destruction is so extensive that there are areas of cavitation (cystic spaces) being formed as the necrotic (mainly liquefied) debris drains out via the bronchi. • Microscopically, caseous necrosis is characterized by acellular pink areas of necrosis, as seen here at the upper right, surrounded by a granulomatous inflammatory process. microscopic examination, • the necrotic focus appears as amorphous granular material • looks like composed of fragmented, coagulated cells • amorphous granular debris enclosed within a distinctive inflammatory border known as a granulomatous reaction • Unlike coagulative necrosis, the tissue architecture is completely obliterated. Fat necrosis • acute pancreatitis • activated pancreatic enzymes escape from acinar cells and ducts, • the activated enzymes liquefy fat cell membranes, • the activated lipases split the triglyceride contained within fat cells. • The released fatty acids combine with calcium to produce grossly visible chalky white areas (fat saponification), • This is fat necrosis of the pancreas. Cellular injury to the pancreatic acini leads to release of powerful enzymes which damage fat by the production of soaps, and these appear grossly as the soft, chalky white areas seen here on the cut surfaces. Foci of fat necrosis with saponification in the mesentery. The areas of white chalky deposits represent calcium soap formation at sites of lipid breakdown. Fat necrosis • the surgeon and the pathologist can identify the lesions • focal areas of fat destruction, typically occurring as a result of release of activated pancreatic lipases into the substance of the pancreas and the peritoneal cavity. • Microscopically, fat necrosis is seen here. Though the cellular outlines vaguely remain, the fat cells have lost their peripheral nuclei and their cytoplasm has become a pink amorphous mass of necrotic material. Fat necrosis/ On histologic examination, • the necrosis takes the form of foci of shadowy outlines of necrotic fat cells, • with basophilic calcium deposits, • surrounded by an inflammatory reaction. Final outcome • in the living patient, most necrotic cells and their debris disappear – enzymatic digestion – fragmentation, – phagocytosis of the particulate debris by leukocytes. • If necrotic cells and cellular debris are not promptly destroyed and reabsorbed, they tend to attract calcium salts and other minerals and to become calcified. • This phenomenon, called dystrophic calcification, Fibrinoid necrosis • is a term used to describe the • histological appearance of arteries in cases of vasculitis • (primary inflammation of vessels) and hypertension, • when fibrin is deposited in the damaged necrotic vessel wall • The small intestine is infarcted. The dark red to grey infarcted bowel contrasts with the pale pink normal bowel at the bottom. Some organs such as bowel with anastomosing blood supplies, or liver with a dual blood suppy, are hard to infarct. This bowel was caught in a hernia and the mesenteric blood supply was constricted by the small opening to the hernia sac. Haemorrhagic necrosis • describes dead tissues that are suffused with extravasated red cells. • This pattern is – seen particularly when cell death is due to blockage of – the venous drainage of a tissue, leading to massive congestion by blood and to subsequent arterial failure of perfusion Gummatous necrosis • tissue is firm and rubbery. As in caseous necrosis the dead • cells form an amorphous proteinaceous mass • • no original architecture can be seen histologically. However, the gummatous pattern is restricted to describing necrosis in the spirochaetal infection • syphilis Patterns of reversible cell injury • cellular swelling • fatty change. Cellular swelling • Cellular swelling appears whenever cells are incapable of maintaining ionic and fluid homeostasis • and is the result of loss of function of plasma membrane energy-dependent ion pumps. Fatty change • Fatty change occurs in hypoxic injury and various forms of toxic or metabolic injury. • It is manifested by the appearance of small or large lipid vacuoles in the cytoplasm and occurs in hypoxic and various forms of toxic injury. • It is principally encountered in cells involved in and dependent on fat metabolism, such as the hepatocyte and myocardial cell. 3 Reactive oxygen metabolites damage cells