lesson6

advertisement

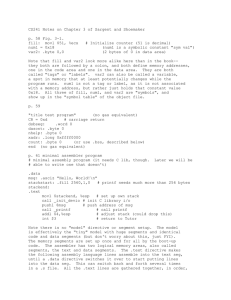

Hexadecimal Notation Using sixteen as a number base when representing binary data Positional Notation (Base 16) • Set of sixteen digit-symbols: 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,A,B,C,D,E,F • Position-values are powers of sixteen: 160 = 1, 161 = 16, 162 = 256, 163 = 4096, … • Write 32-bit addresses using 8 hex digits • Example: This 32-bit binary number 11000000000000000000000000000000 is written more briefly as: C0000000 (hex) ‘nybbles’ • Each hex digit represents 4-bits: 0 = 0000 1 = 0001 2 = 0010 3 = 0011 4 = 0100 5 = 0101 6 = 0110 7 = 0111 8 = 1000 9 = 1001 A = 1010 B = 1011 C = 1100 D = 1101 E = 1110 F = 1111 Conversions • Register AL holds 8 binary digits (bits) • Example: AL = 01100001 (binary) • One byte (8-bits) equals two nybbles: AL = 0110 0001 • Each nybble (4-bits) is just one hex digit: • Example: AL = 61 (hex) Interpreting numbers • • • • Our assembler understands hex notation Assembler also recognizes ‘octal’ (base 8) Notations conform to C language syntax Numbers are assumed decimal (base 10) unless otherwise indicated (via a ‘prefix’) • Example: 50 means ‘fifty’ (base 10) but 0x50 means ‘eighty’ (base 16) and 050 means ‘forty’ (base 8) ASCII-codes in hex • • • • • • Uppercase letter ‘A’ is ascii-code 65 Very often it’s written (in hex) as 0x41 Lowercase letter ‘a’ is ascii-code 97 And very often is written (in hex) as 0x61 Hex makes it easy to ‘see’ the binary data Examples: 0x41 represents 01000001 and 0x61 represents 01100001 • This suggest a way to do ascii conversions Lowercase vs. Uppercase • Ascii-codes for lowercase letters (‘a’-’z’): 0x61, 0x62, 0x63, … , 0x79, 0x7A • Ascii-codes for uppercase letters (‘A’-’Z’): 0x41, 0x42, 0x43, … , 0x59, 0x5A • We can visualize these values as ‘bits’ – lowercase: 01100001, … , 01111010 – uppercase: 01000001, … , 01011010 • We see bit number 5 is where they differ! Using ‘AND’ and ‘OR’ • We can use the ‘bitwise-OR’ operator to convert uppercase to lowercase: i.e., lowercase = uppercase | 0x20; • We can use the ‘bitwise-AND’ operator to convert lowercase to uppercase: i.e., uppercase = lowercase & 0xDF; The ‘toupper.s’ program • We can write an assembly language loop to convert a user’s input into uppercase • Select a 32-bit register to use as a ‘pointer’ • Example: movl $buffer, %ebx • In case EBX points to a lowercase letter, we can convert it to uppercase by using: andb$0xDF, (%ebx) # resets bit 5 to 0 • The ‘b’ suffix here tells the operand’s size The program’s loop again: nochg: movl movl cmpb jb cmpb ja andb incl loop $buffer, %ebx nbytes, %ecx $’a’, (%ebx) nochg $’z’, (%ebx) nochg $0xDF, (%ebx) %ebx again The ‘password’ program main obtain_password request_input verify_validity receive_reply notify_the_user grant_or_refuse Enhanced ‘password’ main obtain_password request_input verify_validity receive_reply notify_the_user use_uppercase grant_or_refuse Typical kinds of loops • ‘while’ loops: So long as a condition is true perform the action in the body of this loop • ‘until’ loops: Perform the action in the body of this loop until condition is no longer true • Note: a while-loop can be empty, but an until-loop always executes at least once enter enter Flowcharts initializations condition initializations FALSE action TRUE TRUE action condition FALSE leave WHILE-LOOP leave UNTIL-LOOP A typical ‘WHILE’ loop movb $FALSE, done again: cmpb $FALSE, done jne finis # the body of the loop goes here # (and may alter the ‘done’ flag) jmp again finis: A typical ‘UNTIL’ loop movb $TRUE, done again: # the body of the loop goes here # (and may alter the ‘done’ flag) cmpb $TRUE, done je again ‘Counted’ loops • Very often we know in advance the number of times that the body of a loop needs to execute • In these cases the loop’s exit-condition is based on the changing value of a counter • Sometimes a counted loop needs to allow for an early exit (before the final count is reached) • Pentium has some special support-instructions: loop and jecxz • Also (for early exits): loope/loopz and loopne/loopnz A typical ‘counted’ loop nxadd: movl movl movl addl addl loop movl $array, %ebx $0, %eax $50, %ecx (%ebx), %eax $4, %ebx nxadd %eax, total Might your count be zero? movl jecxz nbytes, %ecx finis again: # the body of your loop goes here loop again finis: An ‘early exit’ example # gets the first non-blank character from ‘inbuf’ # (where ‘nbytes’ is length of the ‘inbuf’ array) again: movl $inbuf, %esi movl nbytes, %ecx movb (%esi), %al incl %esi cmpb $’ ’, %al loope again