Managerial Accounting

Balakrishnan | Sivaramakrishnan | Sprinkle | Carty | Ferraro

Chapter 11: Managing Long-Lived Resources: Capital

Budgeting

Prepared by Debbie Musil, Kwantlen Polytechnic University

What is Capital Budgeting?

• Significant investments take place

because of many factors

− As time passes, assets wear out and must be

replaced

− Growth in demand has overtaken available

capacity

− Launching new products / market expansion

− Changing production technology

LO1: Understand the reasons for capital budgeting

What is Capital Budgeting?

• Such project decisions have two main

components

− Evaluate Project profitability

− Allocate scarce capital among profitable projects

• Capital budgeting refers to the set of tools

used to evaluate such large expenditures

• Let us begin by linking to two familiar topics

− Cost allocations and budgets

LO1: Understand the reasons for capital budgeting

Link to Cost Allocations

• Both allocations and capital budgeting

deal with capacity decisions

• However, allocations suffer from two

main drawbacks: they do not consider:

− Time value of money

− Lumpy nature of capacity

LO1: Understand the reasons for capital budgeting

Defects: Cost Allocations

• Time value of money

− $1 today is worth more than $1 a year from today!

− Capital assets last for many years. Thus, we need to

consider time value for effective decision making

• In capital budgeting, we discount future cash flows to their

present value so that we can consider projects with

alternate cash flow patterns

• Lumpy nature of capacity

− Capacity resources come in discrete sizes

• Allocations assume “smooth” capacity.

• That is, they allow for capacity to be bought in small

increments. But, we cannot buy 15/16th of a machine.

− Capital budgets explicitly recognize lumpy capacity

LO1: Understand the reasons for capital budgeting

Link To Budgets

• Capital budgets link strategic plans and

operating budgets

• Strategic plans

− Set the vision for the future

− Flesh out core competencies

• Operating budgets (chapter 7)

− Deal with the here and now

− Take capacity resources more or less as a given

• Capital budgets consider both needs as

dictated by operating budgets and plans as

dictated strategically

LO1: Understand the reasons for capital budgeting

Steps in Capital Budgeting

• Identify and evaluate individual proposals

(“screening decisions”)

− Proposed by management as well as others

• Dictated by strategic visions

• Prioritizes proposals and decide which to fund

(“preference decisions”)

− Ability to fund projects limited by capital /

managerial talent

− Fit with strategic profile varies

− Qualitative dimensions (e.g., safety, environment)

might dominate choice

LO1: Understand the reasons for capital budgeting

Elements of Cash Flow for Projects

• Initial Outlay.

− What are the costs associated with acquiring the resource and

getting it ready for use?

• Estimated Life and Salvage Value.

− How long do we expect to keep the resource?

− At the end of this period, what is the cash flow associated with

selling / disposing off the resource?

• Timing and Amounts of Operating Cash Flows.

− What are the expected operating expenses every year?

− What are the expected revenues?

• Cost of Capital.

− What is the opportunity cost of capital required for the proposed

investment?

LO2: List the components of a project’s cash flows

Timeline: Project Cash Flow

LO2: List the components of a project’s cash flows

Cash Flows for MRI Machine

LO2: List the components of a project’s cash flows

Timeline for MRI Machine Cash Flow

How should we evaluate whether

this is a profitable investment?

LO2: List the components of a project’s cash flows

Many Ways To Evaluate Profitability

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

1

2

3

4

1 $62.10 = $100 × 0.621

2 $152.10 = $100 × 1.521

3 $331.20 = $100 × 3.312

4 $811.50 = $100 × 8.115

Net Present Value (NPV)

• NPV is present value of ALL cash flows

• PV of cash flow in period t =

− “r” is the discount rate

− 1/(1+r)t is the discount factor

• The net present value is the sum of all of

the present values of the individual cash

flows

− NPV recognizes a lump sum outflow at the start

− Periodic inflows over the life of the project

− Salvage value

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

NPV of Project

This is a profitable project.

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

Sensitivity analysis

• Can vary discount rates to reflect differing

evaluations of risk associated with the project

• Can also calculate NPV for alternate scenarios

− Lower price to increase demand early on

• Benefit: Higher revenue with greater present value

• Cost: Lower revenue later on (but PV impact is also smaller)

− Usage rates

− Life of asset

• Such extensions are important because we need

to make many assumptions to estimate the cash

flow from this long-lived asset

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

High Discount Rates Lower NPV

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

$52,620

0.877

-$100,000

0.769

$38,450

0.675

$6,750

Thus, the NPV = $6,750 + $38,450 + $52,620 – $100,000 = -$2,180.

We reject the project because it has a negative NPV.

Assumptions in NPV Analysis

• The initial cash outflow takes place at the beginning

of the period.

− This is the reason for not discounting the initial outlay

• Subsequent cash inflows and outflows occur at the

end of the relevant period.

− The net cash flow in year 1 occurs as a lump sum at the

end of year 1, which is time t =1, or a year from time t =

0

• NPV calculations assume that firms reinvest future

cash inflows in projects that yield a return that

equals the cost of capital

• None of these assumptions are particularly realistic

but they are not unreasonable

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

Internal Rate of Return

• Discount rate at which the NPV is zero

• Relation to NPV analysis

− NPV analysis fixes the discount rate and

calculates the present value

− IRR fixes the NPV at zero and calculates the

implied rate

• Project evaluation criterion

− NPV > 0 => project return exceeds cost of

capital

− IRR > Cost of capital => project has positive

NPV

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

Calculating IRR: Unequal Flows

• This can be mathematically challenging

• It is much more convenient to use a

program such as EXCEL.

− @IRR(A1..A10) function gives the IRR for a

set of cash flows in cells A1 to A10

− Remember to keep the signs consistent

• The IRR for the project is 20.87%

• This is a highly profitable project because

the IRR exceeds the cost of capital of 12%

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

Calculating IRR: Equal flows

• This is like an annuity

• Use annuity tables to find annuity Factor

• For a given project life, find rate that has

the relevant annuity factor

• Example: Initial investment $50,000,

$15,000 inflow for 5 years

− Annuity factor = $50,000 / $15,000 = 3.33

− Looking down column for 5 periods, the rate

is between 15% and 16%

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

Assumptions: IRR

• Timing of cash flows

− Same as NPV Analysis

• Initial outflow now at start of period

• Inflows at end of period

• Reinvestment

− Takes place at the calculated IRR

− This is not a good assumption, particularly for

projects with high IRR

• It is possible to construct examples where

the same project has multiple IRRs

− Needs unusual cash flow patterns

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

Comparing NPV and IRR

• Many people prefer NPV to IRR

− Unique answer for NPV

− Reinvestment assumption is more reasonable for

NPV than IRR

• We are more likely to have projects that return the

cost of capital than return a high IRR

− NPV favors larger projects with greater absolute

profit while IRR focuses on profitability without

concern for size

• Both methods have value

− Firms try to rank order projects by both methods

− Unfortunately, the above differences mean that

sometimes the rank ordering of projects may not

be the same

LO3: Apply discounted cash flow techniques

In Excel, enter cash flows in cells A1 to A4

(starting with the –$100,000 for the initial

outlay in A1).

In cell A5, type “=IRR(A1:A4)” and Excel

will reveal that the IRR = 12.40%.

Using the same approach as in Check it!

Exercise #2, we can calculate NPV(12%) =

$550; NPV(13%) = -$820, and confirm the

validity of our estimate. Finally, we reject

the project because its IRR is lower than

the cost of capital (14%).

The

Result

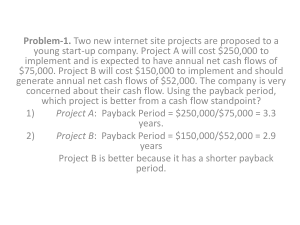

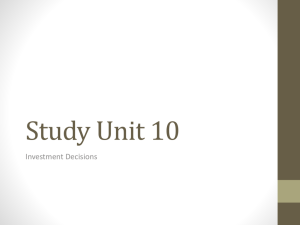

Payback Method

• Payback period is the length of time it

takes to recoup the initial investment

• Initial out flow of $60,000 and periodic

inflows of $24,000

• Payback period = 2.4 years =

$60,000/$24,000.

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Evaluating Payback Method

• Advantages

− It is a simple easy method

− Focuses on the downside risk

• But…

− Ignores the time value of money

− Ignores cash flows that occur after the

payback period

− Not enough emphasis on upside potential

• Acceptable payback period is unclear

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Payback Period for Project

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Cumulative cash inflows through year 5 =

$60,000 year 1

+ $60,000 year 2

+ $60,000 year 3

+ $50,000 year 4

+ $50,000 year 5

= $280,000

Payback period of 5.6 =

5 years + ($310,000 initial investment – $280,000 cumulative

cash inflows through year 5)/$50,000 cash flow in year 6.

Modified Payback

• Calculates the payback period using discounted

cash flows

• Overcomes a major defect of the payback period

• But, it still does not account for cash flows after

the modified payback period

• Overall,

− Payback and modified payback can provide some

measure of risk in project

− But, they are not preferred because of their

shortcomings

− Use as a secondary criterion rather than as the main

rule

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Modified Payback

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Accounting Rate of Return

AR

R

=

Average annual income from the project

Average annual investment

• Annual income = Annual cash flow – depreciation

• Investment = Average book value at start & end of period

• For project:

− Depreciate using the straight-line method and assuming zero salvage

value

− First, we decrease the book value of the equipment by the

depreciation amount

− We then calculate the average investment balance for each year as

the average of the beginning and ending book values

− The final step is to compute ARR as the ratio of the average income

to the average investment over the lifespan of the investment.

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

ARR Calculations

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

ARR: Evaluation

• Easy and straight forward to calculate

• Ties in well with standard “accounting”

measures of performance

• Ignores time value of money

• Ignores patterns of cash flow

− Most suited for simple projects with

somewhat equal cash flows over the life of

the project

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Comparing the Methods

Feature of Method

Net

Present

Value

Considers time value of

money

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

No

Considers all cash flows

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

Return earned on

invested cash inflows

Cost of capital

IRR

Ease of computations

Moderate

Moderate

to difficult

Easy

Easy to

moderate

Easy to moderate

No

No

Yes

Yes

No

No

No

No

No

Yes

Greater focus on

avoiding losses than on

making profit

Integrates well with

accounting performance

measures

Internal

Modified

Rate of Payback

Payback

Return

Not

Not

applicable applicable

Accounting

Rate of

Return

Not applicable

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

Usage Patterns

Often or

Always

Sometimes

Rarely or

Never

NPV

85.1%

10.9%

4.0%

IRR

76.7

15.4

7.9

Payback

52.6

21.9

25.5

Modified Payback

37.6

19.1

43.3

ARR

14.7

18.6

66.7

Source: P.A. Ryan and G. P. Ryan, Capital Budgeting Practices of the Fortune 1000: How have Things

Changed? Journal of Business and Management, Volume 8 (4), 2002.

LO4: Compare various methods for evaluating projects.

The Effect of Taxes

• We can depreciate the cost of a capital

asset over time

− Accounting income = Operating cash flow

less other non-cash items less depreciation

− We focus on the effect of depreciation

• Taxes are paid on accounting income,

NOT cash flow

− Depreciation lowers income and thus taxes

− Provides a tax shield

LO5: Explain the role of taxes and depreciation tax shields.

Calculating the Tax Shield

• Method 1:

− Depreciation tax shield = tax rate × depreciation

− Tax on operating cash flow = t × operating cash

flow

− After-tax cash flow = (1-t) × operating cash flow

+ depreciation tax shield

• Method 2 (Same answer as method 1):

− Calculate Income = Cash flow – depreciation

− Calculate taxes = t × income

− After-tax cash flow = (1-t) × income +

depreciation

LO5: Explain the role of taxes and depreciation tax shields.

Salvage Value and Taxes

• Need to pay taxes on any gain or loss due

to disposal of asset

− Gain/ loss may arise because accounting

depreciation is not always the same as

decline in economic value

• Calculation

− Gain or loss = sale proceeds – Net Book Value

− Net Book Value = Initial investment –

accumulated depreciation

− Note: Tax is paid on the gain / loss and NOT

on the proceeds

LO5: Explain the role of taxes and depreciation tax shields.

$304,000 in year 5 = $370,000 net cash inflow from Exhibit 11.2 –

[($370,000 – $150,000 depreciation expense) x 0.30 in taxes due].

Alternatively, $370,000 – $150,000 = $220,000 in taxable income;

$220,000 x 0.30 = $66,000 in taxes.

Thus, $304,000 = $220,000 in income – $66,000 in taxes + $150,000

in depreciation expense. $346,000 in year 10 = $430,000 net cash

inflow from Exhibit 11.2 – [($430,000 – $150,000 depreciation

expense) x 0.30 in taxes due].

Uncertainty

• Two approaches to cash flow uncertainty:

− Consider a few scenarios using high, medium and

low estimates of revenues or savings

− Do a breakeven calculation on how much annual

cash flows must be in order to have an NPV = 0

• Two approaches to uncertain project life:

− Consider a few scenarios using shorter lives to

determine hw long it takes before NPV = 0

− Do a “discounted payback” calculation to

determine how long it takes for project to pay

for itself

Allocating Capital Among

Projects

• Most firms have limited access to capital,

managerial talent, and other

organizational resources

− Use hurdle rate to select projects

• Hurdle rate > Cost of capital. Why?

− Risk inherent in estimation process

− Reduce slack built into budgets

− Force managers to come up with “best”

projects

LO6: Describe issues in allocating scarce capital among projects

Non-financial Costs and

Benefits

• Many benefits are hard to assess

− Environmental impact

− Worker / consumer safety

− Quality of products (image in marketplace)

• Costs can be difficult as well

− Training

− On-going maintenance

− Effect on other products

• The benchmark is usually the status quo

− But, difficult to evaluate cash flow under status

quo

LO6: Describe issues in allocating scarce capital among projects

Pick The Right Benchmark

LO6: Describe issues in allocating scarce capital among projects

Flexibility

• All projects involve some degree of

uncertainty

• Some projects inherently have more

flexibility than others

− Smaller upfront commitment (“dipping toe in

water”)

− These projects let firms adjust more rapidly to

any new information they may obtain

• Such flexibility (or the option to change

one’s mind) has value

− Usually called a “real” option

LO6: Describe issues in allocating scarce capital among projects

Real Option Analysis

Value of Flexibility

LO6: Describe issues in allocating scarce capital among projects

Exercise 11.31

Present value calculations (LO3).

Refer to the data in the following table:

Setting

Initial outlay

1

Life

Discount rate

Future value

(years)

(compounded

annually)

(at the end of life)

$225,000

5

10%

?

2

?

10

12%

$400,000

3

$157,950

8

?

450,000

4

$150,000

?

12%

$371,400

Required:

Treating each row of the table independently, compute the

missing information. Use the present value/future value

tables in Appendix B.

Exercise 11.31 (Continued)

Treating each row of the table independently, compute the missing information.

Use the present value/future value tables at the end of the book.

For each setting, we use the appropriate present value factors from

the tables in Appendix B. The relevant table and the factor are given

in parentheses for each setting.

Setting

Initial outlay

1

2

Life

Discount rate

Future value

(years)

(compounded

annually)

$225,000

5

10%

$128,800

10

12%

$400,000

(Table 1: Factor 0.322)

(at the end of life)

$362,475

(Table 2: Factor 1.611)

3

$157,950

8

14%

450,000

4

$150,000

8

12%

$371,400

Copyright

Copyright © 2011 John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd. All rights reserved.

Reproduction or translation of this work beyond that permitted by

Access Copyright (the Canadian copyright licensing agency) is unlawful.

Requests for further information should be addressed to the

Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd. The purchaser

may make back-up copies for his or her own use only and not for

distribution or resale. The author and the publisher assume no

responsibility for errors, omissions, or damages caused by the use of

these files or programs or from the use of the information contained

herein.