Untangling Speech and Language Difficulties in

advertisement

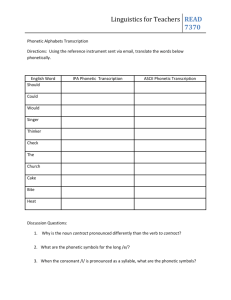

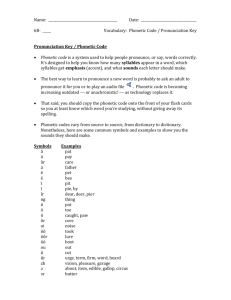

Untangling Speech and Language Difficulties in Toddlers? Bronwyn Carrigg & Dr Elise Baker, December 2009 On behalf of NSW EBP Paediatric Speech Group Some challenges… 1. Our question related to diagnostic evidence Draft CAP-Diagnostic to committee (Dollaghan) 2. Requires reading of speech & language literature 3. Huge body of Late Talker literature underlies the topic (ie can we accurately diagnose language impairment in young children, let alone differentially diagnose speech vs language diffics?) Quick Review: Late Language Emergence (LLE) Subgroups of toddlers with LLE exist; a) Secondary language impairment ass with DD, ASD, HL a) Late Talkers (LT) – no other difficulties or diagnoses, 10 19% of 2 year olds (Klee, 1998, Rescorla, 2002, Rice 08) • • LT - Normal variation – will move into WNL range LT - Primary speech/language impairment - type of primary communication impairment? ie language, phonology, sCAS? The procedures most frequently used to differentiate CN with Language delay’ from those with typical language development are; 1. Parent-report measures of total vocab size; - Language Development Survey (LDS Rescorla 98) - MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Words & Sentences (CDI:WS Fenson et al 93) 2. Parent report of 2-3 word combinations 3. Test battery measuring expressive & receptive lang **Could looking at Speech Markers eg syllable shape, phonetic inventory, or Nonword Repetition in toddlers, add dx info? Clinical Question: For diagnosing speech and language delay in late talking English speaking toddlers, are measures of speech production (e.g., syllable shape, phonetic inventory) and/or nonword repetition as accurate as currently used measures (e.g., CDI, vocabulary size)? 6 papers read by group on this topic. Oller, D.K., Eilers, R.E., Neal, A.R., & Schwartz, H.K. (1999). Precursors to speech in infancy: The prediction of speech and language disorders. Journal of Comm Disorders, 32, 223-245. Canonical babbling: infant’s production of well formed syllables, often in reduplicated sequences ‘bababa’. Mean age of onset 6 months. Rarely begins later than 10 months. True for children from low and very low SES areas. Results: • Infants with confirmed, late onset canonical babbling had smaller expressive vocabularies at 18, 24, 30 months than controls. No sig differences in comprehension. Small sample • <50% who babbled later than 10 months had sig medical dx. They were excluded from follow up studies at 18, 24 months Highman, C., Hennessey, N., Sherwood, M., Leitao, S. (2008) Retrospective parent report of early vocal behaviours in children with suspected Childhood Apraxia of Speech (sCAS). Child Language Teaching & Therapy, 24(3) 285 – 306 Method: Retrospective questionnaire completed by parents of 3 groups of children; sCAS, SLI, and TD. 20 children per group. Questionnaire covered: 1. Developmental milestones 2. Feeding & dribbling behaviours 3. Vocalisations & babbling (eg frequency of sounds, frequency of babble, reduplicated babble, variegated etc) Results (Highman, Hennessy et al 2008): 1. Preliminary support for notion of differences in pre-linguistic vocalisations of children with sCAS. 2. Similarities between sCAS & SLI group cf TD group 3. sCAS & SLI groups differed on following measures; • 35% sCAS group reported never babbled (TD SLI did) • 2 word combinations later for sCAS than SLI & TD • sCAS group met some motor m/stones later SLI & TD 4. No differences between groups for feeding or dribbling Carson, C., Klee, T., Carson, D. & Hime, L (2003) Phonological profiles of 2-year-olds with delayed language development: Predicting clinical outcomes at age 3. AJSLP, 12, 28-39. Phonetic Measures: including the number of; - different consonants - different consonants in IWP/FWP - % closed syllable shapes - diff consonant clusters IWP/FWP Results: preliminary findings. 28 children. 13/28 followed up. • Children with ‘language delay’ -LDS+, Mullen Scales, & MLU significantly lower on all phonetic measures cf TD children. • the more delayed the child’s phonological development at 2 years, the more at risk for continuing problems with language acquisition at 3 years Mirak, J. & Rescorla, L. (1998) Phonetic skills and vocabulary size in late talkers: Concurrent and predictive relationships. Applied Psycholinguistics, 19, 1-17 Investigated 37 LTs ( 24-31 months), comp WNL. 20 TD. 1. • • Relation b/w phonetic inventory & vocabulary size CN with smaller vocabs likely to have limited phonetic reps LTs >difficulty with medial & final consonants than initial 2. Predictive relation b/w these variables & language at 3 yrs • • phonetic skills and size of vocabulary were not predictive severity predicted language outcomes at 3 yrs, ie degree of expressive delay relative to age Williams, L., & Elbert, M. (2003). A prospective longitudinal study of phonological development in late talkers. LSHSS, 34,2 Provides longitudinal, in depth phonological data on 5 late talkers. Seen monthly for 10-12 mths. 3/5 resolved by 33 mths Possible predictive factors: quantitative and **qualitative differences in phonological skills of those who did not catch up. Extent of delay. Age at diagnosis. 2 unresolved cases, hx otitis media. No info on comp, family hx). Preliminary study. < phonetic inventory > sound errors atypical error patterns > simple syllable structure < diversity of syllable structure > variability & inconsistent slower rate of resolution chronological mismatch Stokes, S. & Klee, T (2009) The diagnostic accuracy of a new Test of Early Nonword Repetition for differentiating late talking and typically developing children. JSHR, 52, 872-882 Nonword Repetition: an unbiased Ax of language related ability, requires psycholinguistic processing without relying on meaning • • Could it be a clinical marker of SLI? Could it be used as indicator of early language delay? TENWR: 12 nonwords, 1-4 syllables, eg ‘dafi’, ‘pirduluhmaip’) Results: • 1-3 syllable NWR not useful in differentiating 2 groups • 4 syllable NWR showed better accuracy but small sample size, poor compliance. ‘favourable, preliminary results’ p879 Clinical Bottom Line: • Clinical bottom line for each paper (CAP). • Combined clinical bottom line for the topic (CAT) • Affirm or change practise • Tells clinicians how to apply the available evidence clinically • Is informed by consideration of Level of Evidence, comments on design, and robust discussion among the group. Clinical Question: For diagnosing speech and language delay in late talking English speaking toddlers, are measures of speech production (e.g., syllable shape, phonetic inventory) and/or nonword repetition as accurate as currently used measures (e.g., CDI, vocabulary size)? Clinical Bottom Line: • No definitive study proving these measures are equally reliable or could replaced current methods of practice. • However, research suggests that measures of children's speech and non-word repetition ability that could contribute to the accurate diagnosis of speech/language delay in toddlers. Clinical Bottom Line (cont’d): The focus for many years has been on language of LTs. The research suggests that SLPs may benefit from also considering children's speech production skills (small phonetic inventories, little change in phonological skills over time, small word shape inventory), and their possibly NWR abilities (4-syllables words – preliminary findings). Additional Clinical Bottom Line Information… • There is a relationship between measures of lexical development (eg vocab size, word combinations) and phonetic inventory in LTs. They have smaller vocabularies and reduced phonetic inventories. • The predictive value of either measure not clearly supported over a number of studies. Preliminary investigations suggest qualitative phonological measures (with quantitative measures), and babbling onset and type are potential variables factors for further study • However, severity and age at diagnosis appear to predict language outcomes at 3 years. Older a child is when diagnosed and more severe (greater developmental lag), more likely child has true speech +/or language impairment. Carson, C., Klee, T., Carson, D. & Hime, L. (2003). Phonological profiles of 2-year-olds with delayed language development: Predicting clinical outcomes at age 3. AJSLP, 12, 28-39. Highman, C., Hennessey, N., Sherwood, M., Leitao, S. (2008). Retrospective parent report of early vocal behaviours in children with suspected Childhood Apraxia of Speech (sCAS). CLTT, 24(3) 285 – 306 Mirak, J. & Rescorla, L. (1998) Phonetic skills and vocabulary size in late talkers: Concurrent and predictive relationships. Applied Psycholinguistics 19, 1-17 Oller, D.K., Eilers, R.E., Neal, A.R., & Schwartz, H.K. (1999). Precursors to speech in infancy: The prediction of speech and language disorders. Journal of Communication Disorders, 32, 223-245. Stokes, S. & Klee, T (2009) The diagnostic accuracy of a new Test of Early Nonword Repetition for differentiating late talking and typically developing children. JSHR, 52, 872-882 Williams, L., & Elbert, M. (2003). A prospective longitudinal study of phonological development in late talkers. LSHSS, 34, 2 Thank you to EBP Paed Speech members; SWAHS, SSWAHS, HNEAHS, NSCCAHS, SESIAHS, University of Sydney, Private SPs To join contact; bronwyn.carrigg@sesiahs.health.nsw.gov.au