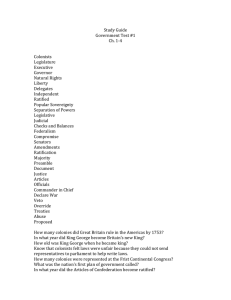

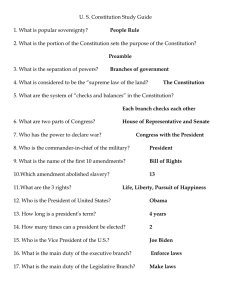

2. The United States Constitution

advertisement