Social media shapes new ethics rules governing lawyers

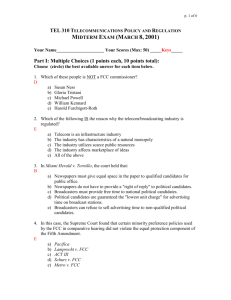

Rules Governing Media

The First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press, but the government still regulates the media in

many ways. This lesson examines the laws, rules and regulations that govern various media outlets.

Media Law: An Overview [Cornell University]

Freedom of the press is a fundamental liberty guaranteed by the First Amendment of the Constitution.

As such, courts and legislative bodies have been hesitant to impinge on that freedom. In fact, there are numerous state and federal statutes that seek to ensure the full extent of the guarantee of the First

Amendment, such as the Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act.

Historically, media law has been divided into two areas: telecommunications and print sources

(newspapers, periodicals, etc.). There are some federal regulations regarding both categories and there are state laws governing both areas as well. The scope of these laws is limited by the First Amendment.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulates interstate and foreign communications by radio, television, wire, satellite, and cable. It was created by the Communications Act of 1934 (47 U.S.C.

151 et seq.) to regulate interstate and foreign communications by wire and radio in the public interest.

Different branches of the media are regulated by different bureaus. The Media Bureau regulates amplitude and frequency modulation, low-power television, direct broadcast satellite, and regulates cable television. The Wireline Competition Bureau regulates telephone and cable facilities. The Wireless

Telecommunications Bureau administers all domestic commercial and private wireless telecommunications programs and policies. The International Bureau manages all international programs. In a sweeping overhaul of the Communications Act of 1934, Congress enacted the

Telecommunications Act of 1996 (47 U.S.C. 51 et seq.). Its goal was to deregulate the industry and encourage competition.

The growth of the Internet and digital media more generally have begun to blur the boundaries between media segments. In 1998, Congress passed the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) to deal with

Internet issues and the advanced technologies used to bypass copy protection devices.

Freedom Of The Press

'Skydiver Lands on Beer Vendor at Women's Cole Slaw Wrestling Event'

'Five-Headed Coach to Lead Washington School'

These are real headlines! You might be wondering if the media can print or broadcast whatever they like. That's not too far from the truth. The U.S. Constitution's First Amendment guarantees freedom of the press. The press doesn't have absolute freedom, but there are only a handful of laws and regulations that limit the media.

There are even laws in place to guarantee openness of information and media freedom, such as the

Freedom of Information Act, or FOIA. The FOIA is a federal law that gives you the right to access information from the federal government. The media makes many FOIA requests to gather information for news reports and articles.

Regulating The Media

Now, let's take a look at some ways the media is limited. It's helpful to note that the print media are largely unregulated. This means that newspapers, newsletters, flyers and magazines can print almost anything they'd like.

The main restriction on the print media comes in the form of defamation. Defamation occurs when someone prints or broadcasts information that is untrue and harmful to someone else. Claims of defamation are usually civil cases governed largely by state law. However, there are some countries and states in the U.S. with criminal defamation laws.

Defamation includes both libel and slander. Libel is defamation of character in print, audio, or video publications. Slander is defamation of character through unrecorded gestures or oral remarks. When someone is defamed through libel or slander, that person can sue the media outlet directly for damages.

Broadcast media is more highly regulated than print media. Broadcasters and networks can still be sued for defamation. However, the broadcast media is also subject to broader, federal regulations. The regulations stem from the historical development of broadcasting.

When radio stations were first used, the stations operated on the same frequencies. This meant they often blocked each other's signals. The Federal Radio Act of 1927 set up licensing procedures to allocate different frequencies to different radio stations because the airwaves were deemed public property. In

1934, Congress enacted the Federal Communications Act. This Act established the Federal

Communications Commission, which continues to manage the broadcast media, and our airwaves, still today.

The FCC And Decency

The Federal Communications Commission, or FCC, is a federal government agency responsible for regulating the public airwaves. The FCC issues licenses and is in charge of controlling everything that uses the airwaves. The FCC serves several roles. For one, the FCC polices the content of the airwaves.

The FCC has the authority to fine broadcasters, or even revoke broadcasting licenses, for violating the

FCC's Public Decency Standards. It's a violation of federal law:

To broadcast obscene programming at any time

To broadcast indecent programming during certain hours

To broadcast profane language during certain hours

The definition of what is obscene, indecent or profane is left to the interpretation of the FCC and the federal courts. Though these provisions may seem vague, they're often used. For example, the FCC fined radio shock-jock Howard Stern so many times that he's been dubbed the 'King of all Fines.' A nearly

Obscene, Indecent and Profane Broadcasts

It’s Against the Law

[FCC Guide]

It is a violation of federal law to air obscene programming at any time. It is also a violation of federal law to air indecent programming or profane language during certain hours. Congress has given the Federal

Communications Commission (FCC) the responsibility for administratively enforcing these laws. The FCC

may revoke a station license, impose a monetary forfeiture or issue a warning if a station airs obscene, indecent or profane material.

Obscene Broadcasts Are Prohibited at All Times

Obscene material is not protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution and cannot be broadcast at any time. The Supreme Court has established that, to be obscene, material must meet a threepronged test:

An average person, applying contemporary community standards, must find that the material, as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest;

The material must depict or describe, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by applicable law; and

The material, taken as a whole, must lack serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value.

Indecent Broadcast Restrictions

The FCC has defined broadcast indecency as “language or material that, in context, depicts or describes, in terms patently offensive as measured by contemporary community standards for the broadcast medium, sexual or excretory organs or activities.” Indecent programming contains patently offensive sexual or excretory material that does not rise to the level of obscenity.

The courts have held that indecent material is protected by the First Amendment and cannot be banned entirely. It may, however, be restricted in order to avoid its broadcast during times of the day when there is a reasonable risk that children may be in the audience.

Consistent with a federal indecency statute and federal court decisions interpreting the statute, the

Commission adopted a rule that broadcasts -- both on television and radio -- that fit within the indecency definition and that are aired between 6:00 a.m. and 10:00 p.m. are prohibited and subject to indecency enforcement action.

Profane Broadcast Restrictions

The FCC has defined profanity as “including language so grossly offensive to members of the public who actually hear it as to amount to a nuisance.” Like indecency, profane speech is prohibited on broadcast radio and television between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.

Enforcement Procedures and Filing Complaints

Enforcement actions in this area are based on documented complaints received from the public about obscene, indecent or profane material. FCC staff will review each complaint to determine whether it contains sufficient information to suggest that there has been a violation of the obscenity, indecency or profanity laws. If it appears that a violation may have occurred, the staff will start an investigation, which may include a letter of inquiry to the broadcast station.

If the description of the material contained in the complaint is not sufficient to determine whether a violation of the statute or FCC rules regarding obscene, indecent and profane material may have occurred, FCC staff will send the complainant a dismissal letter explaining the deficiencies in the complaint and how to have it reinstated. In such a case, the complainant has the option of re-filing the

complaint with additional information, filing either a petition for reconsideration, or, if the decision is a staff action, an application for review (appeal) to the full Commission.

If the facts and information contained in the complaint suggest that a violation of the statute or FCC rules regarding obscenity, indecency and profanity did not occur, FCC staff will send the complainant a letter denying the complaint, or the FCC may deny the complaint by public order. In either situation, the complainant has the option of filing either a petition for reconsideration or, if the decision is a staff action, an application for review (appeal) to the full Commission.

If the FCC determines that the complained-of material was obscene, indecent and/or profane, it may issue a Notice of Apparent Liability (NAL), which is a preliminary finding that the law or the FCC's rules have been violated. Subsequently, this preliminary finding may be confirmed, reduced or rescinded when the FCC issues a Forfeiture Order.

Context

In making obscenity, indecency and profanity determinations, context is key.The FCC staff must analyze what was actually aired, the meaning of what was aired and the context in which it was aired.

Accordingly, the FCC asks complainants to provide the following information:

Information regarding the details of what was actually said or depicted during the broadcast.

The complainant may choose the format for providing the information, but it must be sufficiently detailed so that the FCC can determine the words or language used, or the images or scenes depicted during the broadcast and the context of those words, language, images or scenes. Subject matter alone is not sufficient to determine whether material is obscene, indecent or profane. For example, stating only that the objectionable programming “discussed sex” or had a “disgusting discussion of sex” is not sufficient. Moreover, the FCC must know the context when analyzing whether specific, isolated words or images are obscene, indecent or profane. The FCC does not require complainants to provide tapes or transcripts in support of their complaints. Consequently, failure to provide a tape or transcript of a broadcast, in and of itself, will not lead to automatic dismissal or denial of a complaint. Nonetheless, a tape or transcript is helpful in processing a complaint and, if available, should be provided.

The date and time of the broadcast.

Under federal law, if the FCC assesses a monetary forfeiture against a broadcast station for violation of a rule, it must specify the date the violation occurred. Accordingly, it is important that complainants provide the date the material in question was broadcast. Indecent or profane speech that is broadcast between the hours of 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. is not actionable. Consequently, the FCC must know the time of day that the material was broadcast.

The call sign, channel, or frequency of the station involved.

To take enforcement action for the airing of prohibited material, the FCC must be able to identify the station that aired the material. By providing the call sign, channel or frequency of the station, you will help us to quickly and efficiently process your complaint. The name of the program, DJ, personality, song or film; network; and city and state where you heard or saw the program are also helpful.

Any documentation you provide to the FCC about your complaint becomes part of the FCC’s records and may not be returned.

$500,000 fine in 2004 prompted carrier Clear Channel to drop his show from six different stations.

The FCC And Politics

Besides decency standards, the FCC also regulates broadcasts that involve political campaigns. The FCC uses its Equal Time Rule to ensure that broadcasters provide an opportunity for equal broadcast time to all official candidates running for a particular office. This is why television stations often invite candidates on at the same time to partake in round table talks or debates.

The FCC uses the Right of Rebuttal to ensure that broadcasters provide candidates with an opportunity to respond to criticisms made against them. In other words, a station can't air an attack against one candidate without giving that candidate a chance to respond. You've seen this basic principle at work in the State of the Union address. When the president is a Democrat, a representative of the Republican

Party makes a rebuttal speech known as the Republican Response. The response airs directly after the

State of the Union speech. When the president is a Republican, there is a Democratic Response aired.

Though rarely used, and appealed in 1987, the FCC also had the Fairness Doctrine. This rule stated that a broadcaster who aired a controversial program had to provide time to also air opposing views. For example, if a station aired a documentary on global warming, it would also have to allow time to air programming that disputes global warming. As media outlets grew, and information became more available, the need for the Fairness Doctrine shriveled. It was repealed during the Reagan administration as part of a larger effort toward deregulating several areas of government.

Social media shapes new ethics rules governing lawyers

By Jana Katsuyama

SAN FRANCISCO —

As social media becomes increasingly popular, some say it is posing a threat to the nation's justice system.

Courts have had to draw lines in this age of tweeting and posting on Facebook and blogs to address what jurors, lawyers and judges can do online during jury trials.

For the first time, the American Bar Association is weighing in on the role of social media.

It's a serious concern. One of this country's basic tenets is the right to a fair trial by jury. Judges read orders to the jury to try and ensure the court proceedings are as fair as possible.

In this age of Twitter microblogging and Facebook friending, however, online interactions are leading to problems in courtroom jury trials.

"There have been mistrials created by jurors using social media," said Merri Baldwin, a member of the ethics committee for the State Bar of California.

Baldwin says nationwide, lawyers and even judges have been disciplined for violating court rules around social media.

"There was a famous case involving a judge in North Carolina who actually friended one of the lawyers in the case during the trial," Baldwin told KTVU Friday.

The American Bar Association's ethics committee guidelines issued on Thursday states that a lawyer

"may review a juror's internet presence" while conducting research.

But it states a lawyer "may not send an access request to a juror's social media."

That would include such things as a friend request on Facebook, or ask to connect on LinkedIn to get more information about the juror or potential juror.

Some people say the public might not realize just how much lawyers research jurors online.

One woman who talked with KTVU is a former paralegal.

"I saw how all these research firms and psychologists for big trials are hired to do analysis," said Kathy

Langsam of San Francisco. "I think people will be shocked to see the scrutiny and how everything is researched and looked at."

"Everybody involved in the judicial process is concerned about social media and what it's doing to blur the lines of communication and everyone is searching for clearer and clearer rules that will help guide everybody," said Baldwin.

Baldwin says she expects to see more and more rulings on social media and the courts. She says the ABA guidelines will likely be a model for state bars which set the rules. Attorneys who violate the rules could face punishments ranging from a public reproval to being disbarred