File

advertisement

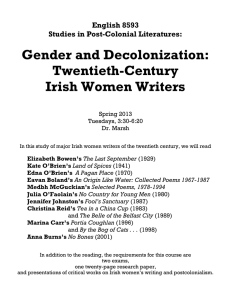

APUSH: On a separate piece of paper analyze three cartoons of your choosing using HAPP. In the nineteenth century, Americans saw Irish people very differently than we might today. Large numbers of Catholic Irish began arriving in the US in the 1850s--numbers in the millions, driven from Ireland by poverty and famine. These immigrants were typically very poor, unskilled, and illiterate. Significant numbers spoke little or no English. The United States was predominantly a Protestant country, and native whites often saw the Irish Catholics as a danger. In this cartoon we can see many of the stereotypes of the Irishman of the 1800s--the association with drink, but also a flat nose, pronounced mouth and lips, low forehead, and general air of brutishness. Below is another typical example. In that cartoon the drunken, violent Irishman sits on a powder keg that threatens the US itself. He has the same pronounced facial features as the character above and below. In this image John Bull (England) and Uncle Sam (the U.S.) debate how to solve the problem of the riotous Irishman, who again has the pronounced lower jaw and mouth, the flat, short nose, and the sloping forehead of a racial inferior. In this image, drunken Irishmen riot against the New York police: Some historians have argued that the Irish were seen as not quite white--not black, exactly, but not quite "white" either. In these cartoons, Irish immigrants are shown as ape-like or as racially different. The cartoon below, for example, makes the contrast explicit. The caption has both the ape and the Irishman proclaiming (in the same accent), that they're glad for the bars between them. Americans in the mid 1800s were just beginning to consider the theory of evolution. Scientists argued that "facial angle" was a sign of intelligence and character. When they studied the "physiognomy" or facial structure, or Irishmen, they detected animalistic qualities. James Redfield's 1852 book Comparative physiognomy; or, Resemblances between men and animals saw Irishmen as dog-like: Redfield mixes claims to science with claims that the Irishman's dog-like character makes him cowardly and cruel. The cartoon above contrasts Clara Barton, the Civil War nurse, with "Bridget McBruiser", a stereotypical Irish woman. It's important to point out that caricatures of immigrants were common. Germans were stereotyped in beer halls; Chinese immigrants were mocked in caricatures and cartoons; African Americans were almost constantly the subject of demeaning comic stereotypes. The point is not that Irish people suffered more or less than any other group: rather, the remarkable thing is how differently Irish people were seen. No one today thinks of Irish people as "not white" or "racially primitive" in some ways, Irish people seem sort of "hyper-white." Irish Americans and African Americans shared many of the same jobs--the low paying, low status jobs native whites avoided. Some historians have pointed out that tap dancing, at which African Americans have excelled, has its roots in Irish dancing, which emphasizes minimal upper body movement and elaborate rhythmic footwork. The predominance of Irish surnames among African Americans points out how much the two groups shared. This cartoonist called attention to what he saw as the similarity between Irish and African immigrants, and the possibility that in America, they would turn into each other: In this cartoon, captioned "A King of -Shanty," the comparison becomes explicit. The "Ashantee" were a well-known African tribe; "shanty" was the Irish word for a shack or poor man's house. The cartoon mocks Irish poverty, caricatures Irish people as ape like and primitive, and suggests they are little different from Africans, who the cartoonists seems to see the same way. This cartoon Irishman has, again, the outthrust mouth, sloping forehead, and flat wide nose of the standard Irish caricature In this next cartoon by Thomas Nast, Irish and African Americans don't look too much alike, but they are the same in terms of their threat to the nation. The caption reads "the ignorant vote." It seems hard to believe that anyone could have looked at Irish people and seen them as "not white." Many historians have argued that "white" is an invented category--that when people looked at each other in the 1800s, they saw many differences--of religion, nationality, ethnicity, language, class. They did not automatically see "white." Here is a final example. This is the marriage certificate of Professor O'Malley's great-great grandfather. He was born in Ireland, but married in 1884 in Virginia to a Virginia native. Look closely at his "race"--and hers. Here is a picture of the happy couple: The State of Virginia, in 1884, regarded these two people as "colored." In popular perceptions that man looked like this: Not quite white, not quite fully human. Again, the point here is not simply that Irish people suffered from bigotry--they certainly did, but many other ethnic groups suffered as much or more. And of course there were many Americans who did not subscribe to these kind of stereotypes. The point is the malleability of our stereotypes. These cartoon images looked like Irishmen and women to people who saw them. Many nineteenth century Americans saw Irish people as a group that simply could not be made "American," as in this cartoon from 1889. They saw them as violent, as non-white, as doomed to poverty and ignorance.