Overhead for the Significance of the Marshall Court

advertisement

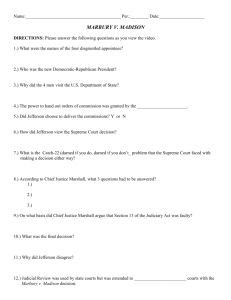

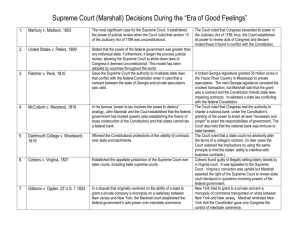

The Significance of the Marshall Court (1801-1835) The Changing Role of the Judiciary • Colonial courts were not an independent entity or separate branch of government (e.g., Thomas Hutchinson in Massachusetts had simultaneously been chief justice of the superior court, lieutenant governor, a member of the council, and judge probate of Suffolk County) • Judges were appointed because of social and political rank, not due to legal expertise • Court performed administrative and executive tasks • In the 1780s, the modern idea of judiciary as a equal and independent branch of government took root. The federal judiciary • Article III creates a Supreme Court and allows for the creation of “such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” • The Judiciary Act of 1789 creates the hierarchical three tiered federal court system Establishing Judicial Independence • Life terms during good behavior • Guaranteed Salary • Removal only by impeachment The Significance of Jurisdiction • Original • Exclusive versus Concurrent • Appellate • District Courts had jurisdiction over admiralty cases, petty crimes, and revenue collection • Circuit Courts served as major trial courts for cases involving out-ofstate or foreign citizens, and over appeals from the district courts in admiralty cases; also had concurrent jurisdiction with state courts in cases with more than 500 hundred dollars at stake and in those with diversity of citizenship (i.e., citizens from different states) • Supreme Court—justices rode circuit and initially heard few cases (only 87) before the 1801 term. Also had a rule that the justices would drink wine only on rainy days. Do federal courts have jurisdiction over common law crimes? • For example, can you punish seditious libel without Congress passing a sedition act? • Federalists and Republicans provided different answers to this question in the 1790s. • The Supreme Court finally resolved this issue in United States v. Hudson (1812) The Retirement of Oliver Ellsworth • What’s a President to do? • The Political Environment in mid December 1800 • How does John Adams decide? Overview “The most important achievement of the Marshall Court (1801-1835) was not particular landmark rulings but rather its elevation of the Court’s stature. Had the justices not begun aggressively exercising the power of judicial review when they did, the Court might never have become a coordinate branch of the national government. In 1801, it certainly was not. That year, John Jay declined President John Adams’s offer to reappoint him chief justice, observing that the federal judicial system was “so defective” that it could never obtain “the energy, weight, and dignity which are essential to its affording due support to the national government.” – Michael Klarman The Final Days of the Adams Administration • Interregnum • The Judiciary Act of 1801: 16 new circuit court judges; blanket power to appoint justices of the peace for the District of Columbia; and changing the number of Supreme Court Justices • Secretary of State John Marshall, a moderate Federalist who had opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts, becomes Chief Justice John Marshall. The Republicans Respond • President Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison Refuse to Send Commissions • The Republican Congress passes the Repeal Act of 1802 and abolishes the 1802 term of the Supreme Court The Fragile State of Judicial Independence • • • • The Threat of Impeachment How to use this power? Impeaching Judge John Pickering The Impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase Marshall’s Dilemma • Although Jefferson and Marshall are cousins, they intensely dislike one another. • If the Supreme Court declares the 1802 repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801 unconstitutional, then the Republicans in Congress might destroy the judiciary. • What would happen if the Supreme Court ordered President Jefferson to issue Marbury’s commission, but he refused? The Eloquence of Marshall • “All of his eloquence consists in the apparently deep self conviction and emphatick earnestness of his manner; the correspondent simplicity and energy of his style; the close and logical connexion of his thoughts; and the easy gradations by which he opens his lights on the attentive minds of his hearers. The audience is never permitted to pause for a moment. There is no stopping to weave garlands of flowers, to hang in festoons, around a favourite argument. On the contrary, every sentence is progressive; every idea sheds new light on the subject; the listener is kept perpetually in that sweetly pleasurable vibration, with which the mind of man always receives new truths; the dawn advances in easy but unremitting pace; the subject opens gradually on the view; until, rising, in high relief, in all its native colours and proportions, the argument is consummated, by the conviction of the delighted hearer. . . .” – William Writ The Sophistry of Marshall • “[W]hen conversing with Marshall, I never admit anything. So sure as you admit any position to be good, no matter how remote from the conclusion he seeks to establish, you are gone. So great is his sophistry you must never give him an affirmative answer, or you will be forced to grant his conclusion. Why, if he were to ask me whether it were daylight or not, I’d reply, ‘Sir, I don’t know, I can’t tell.” – Thomas Jefferson Marshall and Order In the order in which the court has viewed this subject, the following questions have been considered and decided. 1. Has the applicant a right to the commission he demands? 2. If he has a right, and that right has been violated, do the laws of his country afford him a remedy? 3. If they do afford him a remedy, is it a mandamus issuing from this court? A Political Interpretation • The decision is an ingenious way to criticize President Jefferson, while simultaneously preventing him from retaliating. • “By posing the questions in this unusual order Marshall was able to make his point without having to suffer the consequences. As Jefferson and other Republicans pointed out, the Court in its final question disclaimed all cognizance of the case, but in the first two questions declared what its opinion would have been if it had cognizance of it.” – Gordon Wood, Empire of Liberty, 441. The Immediate Aftermath • Jefferson angered by Marshall’s “twistifications” • Six days later, the Court hands down its opinion in Stuart v. Laird • The Marshall Court never again declares an act of Congress unconstitutional The Marshall Court before the War of 1812 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The Role of the Chief Justice From seriatim opinions to the Court speaking with an unitary voice (During the first four years of his tenure, the Court handed down forty-six written opinions. They were all unanimous. Moreover, Marshall participated in 42 of them and wrote the opinion in all 42; between 1801 and 1815 Marshall, in fact, wrote 209 of the Court’s 378 opinions!) Avoiding a confrontation with the Republicans, while simultaneously establishing the right to review and reverse state court decisions Separating Law from Politics Making questions of vested property rights into exclusively judicial issues American Nationalism • The War of 1812 • The Rise of Nationalism • Martin v. Hunter’s Lessee (1816): The Court rejected the claim that Virginia and the national government were equal sovereigns. Reasoning from the Constitution, Justice Story affirmed the Court's power to override state courts to secure a uniform system of law and to fulfill the mandate of the Supremacy Clause. Looking Forward “Never was there a more glorious opportunity for the Republican party to place themselves permanently in power. . . .Let us extend the national authority over the whole extent of power given by the Constitution. Let us have great military and naval schools; an adequate regular army; the broad foundation laid of a permanent navy; a National bank; a national system of bankruptcy; a great Navigation act; a general survey of our ports, an appointment of port wardens and pilots; Judicial Courts which shall embrace the whole Constitutional powers; national notaries; public and national justices of the peace, for the commercial and national concerns of the United States. “ Associate Justice Joseph Story, 1815 The Marshall Court and Constitutional Nationalism • Who made the Constitution? • The People • How should the Constitution be interpreted? • Broadly • Who should interpret the Constitution? • Federal Courts • What powers does the Federal Government have? • Necessary + Proper = Enumerated + Implied The Bank Question Revisited in 1819 Washington’s Cabinet in 1791 Chief Justice John Marshall and Associate Justice Joseph Story The McCulloch Questions • The first question made in the cause is -- has Congress power to incorporate a bank? • The power now contested was exercised by the first Congress elected under the present Constitution. The bill for incorporating the Bank of the United States did not steal upon an unsuspecting legislature and pass unobserved. Its principle was completely understood, and was opposed with equal zeal and ability. After being resisted first in the fair and open field of debate, and afterwards in the executive cabinet, with as much persevering talent as any measure has ever experienced, and being supported by arguments which convinced minds as pure and as intelligent as this country can boast, it became a law. The original act was permitted to expire, but a short experience of the embarrassments to which the refusal to revive it exposed the Government convinced those who were most prejudiced against the measure of its necessity, and induced the passage of the present law. It would require no ordinary share of intrepidity to assert that a measure adopted under these circumstances was a bold and plain usurpation to which the Constitution gave no countenance. These observations belong to the cause; but they are not made under the impression that, were the question entirely new, the law would be found irreconcilable with the Constitution. Who made the Constitution? • In discussing this question, the counsel for the State of Maryland have deemed it of some importance, in the construction of the Constitution, to consider that instrument not as emanating from the people, but as the act of sovereign and independent States. The powers of the General Government, it has been said, are delegated by the States, who alone are truly sovereign, and must be exercised in subordination to the States, who alone possess supreme dominion. • It would be difficult to sustain this proposition. The convention which framed the Constitution was indeed elected by the State legislatures. But the instrument, when it came from their hands, was a mere proposal, without obligation or pretensions to it. It was reported to the then existing Congress of the United States with a request that it might be submitted to a convention of delegates, chosen in each State by the people thereof, under the recommendation of its legislature, for their assent and ratification. • This mode of proceeding was adopted, and by the convention, by Congress, and by the State legislatures, the instrument was submitted to the people. They acted upon it in the only manner in which they can act safely, effectively and wisely, on such a subject -- by assembling in convention. It is true, they assembled in their several States -- and where else should they have assembled? No political dreamer was ever wild enough to think of breaking down the lines which separate the States, and of compounding the American people into one common mass. Of consequence, when they act, they act in their States. But the measures they adopt do not, on that account, cease to be the measures of the people themselves, or become the measures of the State governments. Marshall’s Broad Reading of Necessary and Proper Clause • 1st. The clause is placed among the powers of Congress, not among the limitations on those powers. • 2d. Its terms purport to enlarge, not to diminish, the powers vested in the Government. It purports to be an additional power, not a restriction on those already granted. No reason has been or can be assigned for thus concealing an intention to narrow the discretion of the National Legislature under words which purport to enlarge it. The framers of the Constitution wished its adoption, and well knew that it would be endangered by its strength, not by its weakness. Had they been capable of using language which would convey to the eye one idea and, after deep reflection, impress on the mind another, they would rather have disguised the grant of power than its limitation. If, then, their intention had been, by this clause, to restrain the free use of means which might otherwise have been implied, that intention would have been inserted in another place, and would have been expressed in terms resembling these. "In carrying into execution the foregoing powers, and all others,“ &c., "no laws shall be passed but such as are necessary and proper." Had the intention been to make this clause restrictive, it would unquestionably have been so in form, as well as in effect. The McCulloch Test We admit, as all must admit, that the powers of the Government are limited, and that its limits are not to be transcended. But we think the sound construction of the Constitution must allow to the national legislature that discretion with respect to the means by which the powers it confers are to be carried into execution which will enable that body to perform the high duties assigned to it in the manner most beneficial to the people. Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the Constitution, are Constitutional. The Rejoinder: Compact Constitutionalism • Who made the Constitution? • The States • How should the Constitution be interpreted? • Strictly • Who should interpret the Constitution? • The States • What powers does the Federal Government have? • Enumerated only (10th Amendment) The Marshall Court and the Legacy of Federalism “By the end of Marshall’s tenure, the situation was very different. The Court had established its authority to invalidate state and congressional legislation and to review state court decisions involving federal law issues. It had rejected compact theory, authorized a vast increase in the power of the national government, and imposed significant constraints on the ability of states to interfere with national markets and with contract rights. In 1830 the astute French observer Alexis de Tocqueville noted, “The peace, the prosperity, and the very existence of the Union are vested in the hands of the seven Federal judges [of the Supreme Court].” Twenty years later, unable to resolve the nation’s most contentious political issue, congressional leaders invited the Court to determine the fate of slavery in the federal territories. One cannot imagine Congress in 1800 entrusting the justices with such responsibility.” – Michael Klarman Further Readings Richard E. Ellis, Aggressive Nationalism: McCulloch versus Maryland and the Foundation of Federal Authority in the Young Republic (Oxford University Press, 2007). The most comprehensive history of this landmark decision. George Lee Haskins and Herbert A. Johnson, History of the Supreme Court of the United States. Vol. 2: Foundations of Power: John Marshall, 1801-1815 (MacMillan, 1981). This volume is part of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise History of the Supreme Court of the United States. G. Edward White, The Marshall Court and Cultural Change, 1815-1835 (MacMillan, 1988). This volume places the Marshall Court into a larger cultural context.