Impingement in the Hip * Cam, Pincer or is it a Mixed Bag?

advertisement

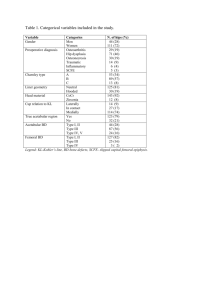

Impingement in the Hip – Cam, Pincer or is it a Mixed Bag? SCOTT BISSELL, MD CONNECTICUT ORTHOPEDIC ASSOCIATES AUGUST 4, 2015 Overview Anatomy Terminology Cam impingement Pincer impingement Pathophysiology FAI and OA Prevalence of FAI Diagnosis Treatment Options Questions Basic Hip Anatomy Background Femoroacetabular Impingement (FAI) first described in the early 1990’s Increasingly recognized as a source of hip pain and dysfunction Pathomechanics Work by Ganz et al FAI caused by repetitive abutment of a morphologically abnormal proximal femur and/or acetabulum during terminal range of motion of the hip This process eventually leads to damage of the acetabular labrum and cartilage dependent on the location of the osseous abnormality Two most common osseous abnormalities Abnormal femoral head-neck offset Acetabular over-coverage Third described type as “mixed” or “combined” Cam Impingement Most common form of isolated FAI Typically seen in young adult males (age 20-30) Loss of normal femoral head-neck contour may be due to: Abnormal extension of the proximal femoral epiphysis Short or long femoral neck Varus femoral neck Perthes Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) Cam Impingement The non-spherical portion of the anterolateral femoral head produces a shear force on the chondrolabral junction as it enters the acetabulum in hip flexion Over time, repetitive shear force results in Chondrolabral separation Acetabular chondral delamination Labral detachment Pincer Impingement Most commonly seen in women ages 30-40 Acetabular overcoverage Focal overcoverage at the anterior superior rim Relative anterior overcoverage (acetabular retroversion) Global overcoverage Protrusio acetabuli Coxa profunda Pincer Impingement Acetabular overcoverage results in crushing of the labrum against the normal femoral neck in hip flexion and internal rotation Continued abutment results in Labral degeneration Chondral injury Possible ossification of the rim Contracoup mechanism can result in damage to the posterior femoral head and acetabulum as the femoral head levers anteriorly Combined Impingement Most common type of FAI (72% - 86%) Components of both cam and pincer impingement although typically one is the dominant component FAI and its Role in the Development of Osteoarthritis Morphological abnormalities of the femoral head and/or acetabulum Abnormal contact between the femoral head and acetabular margin Supraphysiologic stress resulting in tearing of the labrum and avulsion of underlying cartilage Further deterioration and wear – eventual onset of OA FAI and OA Questions Is FAI the cause or the effect of OA? Are the deformities seen in FAI developmental or congenital or possibly a reaction to the OA (analogy osteophyte formation)? Future directions Identify which patients with FAIrelated morphologic abnormalities are at greatest risk for developing hip OA, especially at a young age Should we intervene in the asymptomatic hip with FAI to hopefully prevent OA in the future? Prevalence of FAI Ochoa et al reviewed x-rays of 155 patients (age 18-50) presenting with hip pain 87% had one findings consistent with FAI 81% had two findings consistent with FAI Reichenbach et al reported on 1080 symptomatic military recruits in Switzerland 430 selected randomly and 244 had MRI scans Mean age 19 years Prevalence of CAM deformity was 24% Prevalence of FAI Hack et al studied 200 asymptomatic volunteers using MRI Mean age 29.4 years α- angle measured at two positions 53% had evidence of CAM morphology (α- angle >50.5°) What does this mean? Highlights the importance of clinical correlation during the diagnostic work-up for FAI Diagnosis of FAI Patient history Physical exam Selective intra-articular injections Radiology Plain radiographs CT scan MRI and MRA (magnetic resonance arthrography) Patient History Trauma Childhood hip disease SCFE Perthes Developmental dysplasia Symptoms Pain What positions? What activities? Clicking, popping, catching Stiffness Distribution of pain Typically groin pain (83%) May occasionally radiate to L/S spine, lateral hip Typical patient is young and active participating in activities requiring repetitive hip flexion Physical Exam Often patients indicate deep interior hip pain with the “C-sign” Radiographic Evaluation Plain radiographs AP pelvis 45 degree Dunn view Lateral False profile CT scan MRI or MRA Plain Radiographs AP pelvis 45 degree Dunn view Plain Radiographs Frog Lateral View False Profile View Alpha angle Measure of the degree of asphericity and cam impingement at the anterior head-neck junction Noltzi et al: FAI patients (74°) and normal controls (42°) Findings Associated with CAM Impingement Fibrocystic change at the headneck junction CAM lesion Moving to the Acetabular Side Acetabular Version Acetabular Version Anteverted Acetabulum Retroverted Acetabulum Findings Associated with Pincer Impingement Coxa Profunda Acetabular Protrusio Lateral Center Edge Angle Above 40° may indicate overcoverage Below 25° may indicate dysplasia – structural instability Acetabular Dysplasia Dysplasia or undercoverage Normal for comparison MRI/MRA Imaging of the Labrum Normal Hip Labrum Chondrolabral Separation Clinical Summary Management Options for FAI Non-operative Operative Arthroscopic Open Combined Arthroscopic and Open Non-Operative Management Activity modification Anti-inflammatory medication Injections Intra-articular Extra-articular Iliopsoas Trochanteric Physical therapy Core strength Flexibility (though increased hip ROM SHOULD NOT be the goal of treatment) Data suggests that symptomatic patients with mild deformity may improve with nonsurgical management Emara et al reported on 37 patients with αangle <60° treated with PT and activity modification followed at 2 years 11% chose surgical management 16% experienced recurrent symptoms 89% had significant improvement in mean Harris hip score Surgical Management Goals Improve pain Improve range of motion Improve function Perhaps decrease the risk of future progression to the OA – concept of “hip preservation” Address the pathology Reshape the acetabular rim Recontour the femoral head-neck junction Debride, repair, or reconstruct the labrum Address articular cartilage lesions Surgical Planning – Open vs Arthroscopic Approaches Patient characteristics Disease pattern Location and extent of CAM Complex proximal femoral deformities Surgeon preference and comfort Surgical Approaches Open Surgical Dislocation Initial description by Ganz et al Protects the vascular supply from the medial circumflex artery and its lateral retinacular branches Requires a trochanteric osteotomy preserving the abductor attachments Hip is dislocated anteriorly allowing access to the acetabulum and proximal femur Outcomes of Surgical Dislocation Ganz et al and Beck et al Peters and Erickson reported on 30 hips Mean 4.7 years follow-up Good to excellent in 13 of 19 hips(68%) Mean 2.7 years follow-up HHS improved Presence of Tonnis grade 2 or greater changes increased risk of failure 13.3% conversion rate to THA More recent data (not this study) suggests THA rate now 0-5% Espinosa et al 28% rate of excellent outcomes with labral debridement (combined good/excellent 76%) 80% rate of excellent outcomes with labral repair (combined good/excellent 94%) Complications of Surgical Dislocation Osteonecrosis (although reports are lacking to support this) Nonunion of trochanteric osteotomy (0-3%) Trochanteric pain (46% of all patients and 74% of female patients in one study) Intra-articular adhesions (up to 6% of cases) Sink et al Multicenter cohort of 334 hips undergoing surgical hip dislocation Overall complication rate of 9% Hip Arthroscopy Introduced in the late 1970s and initially was used to manage labral tears and loose bodies Specialized equipment Distraction table Fluoroscopy Long instrumentation Access central and peripheral compartments via small “portal” incisions Hip Arthroscopy Hip Arthroscopy Outcomes – Hip Arthroscopy Multiple studies Success rate of 67% to 90% Rates of conversion to THA 0-9% Retrospective studies Larson et al compared outcomes of rim trimming with labral debridement (LD) vs labral repair (LR) 67% good/excellent with LD 90% good/excellent with LR Nepple et al found that treatment of the bony deformity was associated with significantly greater improvement and decreased failure rates Complications of Arthroscopic Hip Surgery Complication rate 1% to 6% Persistent pain Iatrogenic labral and articular cartilage damage Instability Extravasation of fluid into adjacent spaces (ex. retroperitoneal) Heterotopic ossification (may be up to 8% in untreated patients) Fracture Nerve damage Adhesions Avascular necrosis Combined Arthroscopic and Open Approach Can allow for address of complex deformities that may not be completely accessible via arthroscopy Complex deformities or structural instability may require open procedures Dysplasia Abnormal femoral anteversion Trochanteric impingement Summary CAM impingement on the femoral side Some patients may be treated without surgery Pincer impingement on the acetabular side Surgical options include: Most cases of FAI are combined CAM and pincer Radiographic findings of CAM and pincer impingement exist in the normal asymptomatic population Arthroscopic intervention Open surgical dislocation Combined approach Surgery - regardless of approach - offers reliable good/excellent outcomes in properly selected patients with a low complication rate Thank You Journal of the AAOS 2013; Vol 21, Supplement 1