Gardner's Art Through the Ages, 12e

advertisement

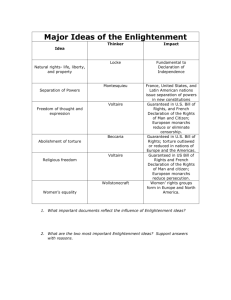

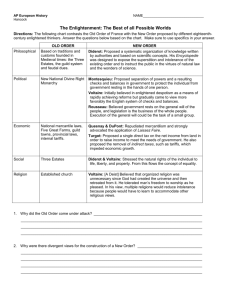

Gardner’s Art Through the Ages, 12e Chapter 28 The Enlightenment and its Legacy: Art of the Late 18th through the Mid-19th Century Napoleonic Europe 1800-1815 THE ENLIGHTENMENT: PHILOSOPHY AND SOCIETY The Enlightenment expanded the boundaries of European knowledge. It offered a new way of thinking critically about the world and about humankind. The Enlightenment employed reason and empirical evidence, and promoted the scientific method. The Doctrine of Empiricism : The Doctrine of Empiricism, promoted by John Locke, argued that the mind is a blank tablet upon which our experience of the material world, acquired through the senses, is imprinted. Ideas are formed on the basis of this experience. Locke also believed that the law of Nature grants people the natural rights of life, liberty, and property, and that the purpose of government is to protect these rights. The Doctrine of Progress : The philosophies in France identified individuals and societies-at-large as part of physical nature and argued that through the application of reason and common sense the problems of society could be remedied. They believed that knowledge was the basis of freedom and that through knowledge societies could be systematically improved. Scientific Art of the Enlightenment • The Enlightenment and the interest in science and the natural world had a strong effect on artistic expression. • Since the Renaissance, artists had been concerned with learning about the body by dissecting it. As that description became more exact and complete, the anatomical artists skill became a specialty. • Joseph Wright of Derby’s series of candlelit scenes departed from previous painting conventions by depicting a scientific subject in the reverential manner formerly reserved for scenes of historical or religious significance, illustrating the increasing status of science in society. • The Industrial Revolution in England in the late 18th century saw technological improvement in iron, allowing it to be used in a variety of new ways --- including bridges, etc. WILLIAM HUNTER, Child in Womb, drawing from dissection of a woman who died in the ninth month of pregnancy, from Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus, 1774. JOSEPH WRIGHT OF DERBY, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture at the Orrery (in which a lamp is put in place of the sun), ca. 1763–1765. Oil on canvas, 4’ 10” x 6’ 8”. Joseph Wright of Derby's realistic painting shows a demonstration of an orrery, the mechanism of which is scrupulously and accurately rendered. JOSEPH WRIGHT OF DERBY, An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, ca. 1768. ABRAHAM DARBY III and THOMAS F. PRITCHARD, iron bridge at Coalbrookdale, England (first cast-iron bridge over the Severn River), 1776–1779. 100’ Enlightenment's champion: Houdon's marble bust shows Voltaire, whose writings and critical activism contributed to the conviction that fundamental changes were necessary in government in order for humankind to progress. Jean-Antoine Houdon Portrait Bust of Voltaire white marble, 1778 • VOLTAIRE VERSUS ROUSSEAU: SCIENCE VERSUS THE TASTE FOR THE "NATURAL“ While Voltaire thought the salvation of humanity was in science's advancement and in society's rational improvement, Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed that the arts, sciences, society, and civilization in general had corrupted "natural man" and that humanity's only salvation was to return to its original condition. The taste for the "natural" in France: Rousseau placed feelings above reason as the most "natural" of human expressions and called for the cultivation of sincere, sympathetic, and tender emotions. Because of this belief, he exalted as a model for imitation the unsullied emotions and the simple, honest, uncorrupt "natural" life of the peasant. The Sentimentality of Rural Romance: The expression of sentiment is apparent in Jean-Baptiste Greuze's much-admired painting of The Village Bride, which shows a peasant family in a rustic interior. JEAN-BAPTISTE GREUZE, The Village Bride, 1761. Oil on canvas, 3’ x 3’ 10 1/2”. Louvre, Paris. JEAN-BAPTISTESIMÉON CHARDIN, Grace at Table, 1740. Oil on canvas, 1’ 7” x 1’ 3”. Louvre, Paris. ÉLISABETH LOUISE VIGÉE-LEBRUN, SelfPortrait, 1790. Oil on canvas, 8’ 4” x 6’ 9”. Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. William Hogarth English painter and engraver, was one of the leading British artists of the first half of the 18th century. He was trained as an engraver and in 1731, he executed his first series of modern morality paintings, a totally new concept intended for wider dissemination through engraving. A Rake's Progress (c1735, eight scenes) and Marriage a la Mode (c1743, six scenes). These series of narrative paintings & prints followed a character or group of characters in their encounters with some social evil. Hogarth compared his sequential paintings to theatrical performances, and thus in each series, minor vices and social affectations are incidentally satirized as the main theme - the punishment of a major vice - takes centre stage. Gin Lane. 1751. Engraving. The British Museum, London, UK. This is Scene 1 of the series of six, entitled The Marriage Settlement. The theme, an unhappy marriage between the daughter of a rich, miserly alderman merchant and the son of an impoverished earl. The series thus begins with the proud Earl pointing to his family tree rooted in William the Conqueror; he rests his gouty foot - a sign of degeneracy - on a footstool decorated with his coronet. Behind him is a lavish building in the new classical style, unfinished for lack of money; a creditor is thrusting bills at him. But on the table in front of him is a pile of gold - the bride's dowry just handed him by the bespectacled alderman, who holds the marriage contract. Silvertongue, an ingratiating lawyer, whispers in the ear of the alderman's daughter listlessly twirling her wedding ring on a handkerchief. Turning away from her to take snuff and admire himself in the glass and, in the engraving, to lead our eye into the next tableau - is the foppish bridegroom. At his feet, symbolic of the couple's plight, are a dog and a bitch chained to each other. From the walls horrid Italian Old Master martyrdoms presage tragedy, and a Gorgon's head screams from an oval frame above the pair. In Marriage a’ la Mode, the husband and wife are tired after a long night spent in separate pursuits. While the wife was at home for an evening of cards andmusic-making, here young husband had been away for a night of suspicious business. His hands are thrust deep into his empty breeches, while his wife’s dog sniffs inquiringly at a lacy woman’s cap protruding from his coat pocket. A steward, his hands full of unpaid bills, raises his eyes to heaven in despair at the actions of his noble master and mistress. WILLIAM HOGARTH, Breakfast Scene, from Marriage à la Mode, ca. 1745. Oil on canvas, approx. 2’ 4” x 3’. National Gallery,