Doctor John Snow Blames Water Pollution for Cholera Epidemic

advertisement

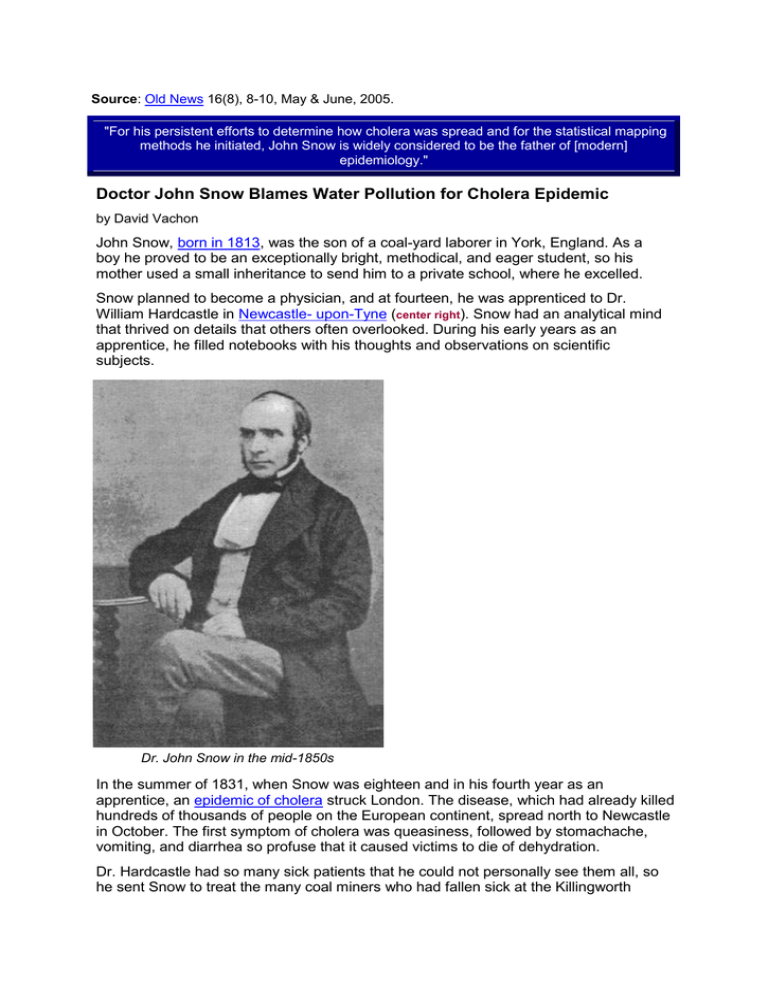

Source: Old News 16(8), 8-10, May & June, 2005. "For his persistent efforts to determine how cholera was spread and for the statistical mapping methods he initiated, John Snow is widely considered to be the father of [modern] epidemiology." Doctor John Snow Blames Water Pollution for Cholera Epidemic by David Vachon John Snow, born in 1813, was the son of a coal-yard laborer in York, England. As a boy he proved to be an exceptionally bright, methodical, and eager student, so his mother used a small inheritance to send him to a private school, where he excelled. Snow planned to become a physician, and at fourteen, he was apprenticed to Dr. William Hardcastle in Newcastle- upon-Tyne (center right). Snow had an analytical mind that thrived on details that others often overlooked. During his early years as an apprentice, he filled notebooks with his thoughts and observations on scientific subjects. Dr. John Snow in the mid-1850s In the summer of 1831, when Snow was eighteen and in his fourth year as an apprentice, an epidemic of cholera struck London. The disease, which had already killed hundreds of thousands of people on the European continent, spread north to Newcastle in October. The first symptom of cholera was queasiness, followed by stomachache, vomiting, and diarrhea so profuse that it caused victims to die of dehydration. Dr. Hardcastle had so many sick patients that he could not personally see them all, so he sent Snow to treat the many coal miners who had fallen sick at the Killingworth Colliery. There was little that Snow could do to help the stricken miners, because the usual treatments for disease-bleeding, laxatives, opium, peppermint, and brandy -were ineffective against cholera. Snow continued to treat cholera patients until February of 1832, when the epidemic ended as suddenly and mysteriously as it had begun. By that time, it had left fifty thousand people dead in Great Britain. During the next sixteen years, Snow earned an M.D. degree, moved to London, became a practicing physician, and distinguished himself by making the first scientific studies of the effects of anesthetics. By testing the effects of precisely controlled doses of ether and chloroform on many species of animals, as well as on human surgery patients, Snow made the use of those drugs safer and more effective. Surgeons who wished to anesthetize their patients no longer risked killing them by the unscientific application of chloroform-soaked handkerchiefs to their faces.px Snow remained a bachelor, with extremely regular habits; his social life consisted mainly of discussing ideas at the regular meetings of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society. He did a lot of thinking about the possible causes of contagious diseases, and he came to the unconventional conclusion that they might be caused by invisibly tiny parasites. This was not an original idea, but it was an unpopular one during the first half of the nineteenth century. The "germ theory" of disease had first been proposed in ancient times, and the discovery of microscopic organisms in the late 1600s had made the theory seem plausible, but no one had ever proved that miniature organisms could make people sick. In Snow's day most physicians believed that cholera was caused by "miasmas" -poisonous gases that were thought to arise from sewers, swamps, garbage pits, open graves, and other foul-smelling sites of organic decay. Snow felt that the miasma theory could not explain the spread of certain diseases, including cholera. During the outbreak of 1831, he had noticed that many miners were struck with the disease while working deep underground, where there were no sewers or swamps. It seemed most likely to Snow that the cholera had been spread by invisible germs on the hands of the miners, who had no water for hand-washing when they were underground. In September of 1848, when Snow was thirty-five, a new outbreak of cholera struck London. He decided to track the progress of the disease. to see if he could determine exactly how it was spread. He learned that the first victim, John Harnold, a merchant seaman, had arrived from Hamburg by ship on September 22. Harnold had gone ashore and rented a room in the London community of Horsleydown where he had quickly developed cholera symptoms and died. Snow spoke with the attending physician who, just a few days after Harnold's death, had been called back to the same room to treat another man, named Blenkinsopp, who had rented the room after Harnold Blenkinsopp had contracted cholera shortly after renting the room and had died eight days later. Snow viewed the second death as strong evidence of contagion. He suspected that the room had not been cleaned after Harnold's occupancy and that perhaps some cholera germs had remained in the bed linen. As more cases appeared, Snow began examining sick patients. All of them reported that their first symptoms had been digestive problems. Snow reasoned that this proved that the disease must be ingested with polluted food or water. If the victims had absorbed cholera poison from polluted air, as the "miasma" theorists believed, then their first symptoms should have appeared in their noses or lungs -- not in their digestive tracts. Snow theorized that the extreme diarrhea that characterized the disease might be the mechanism that spread the germs from one victim to another. Perhaps the fatal germs were lurking in the great volumes of colorless fluid that patients expelled. If just a few drops of that fluid contaminated a public water supply, the disease germs could be spread to countless new victims. Snow discussed his theory with colleagues. He searched through medical journals and government reports about cholera looking for references to water conditions and sewer facilities, and he sent written queries about water conditions and sewer facilities to authorities in areas with high mortality from the disease. In August of 1849, during the second year of the epidemic, Snow felt obliged to share what he considered convincing evidence that cholera was being spread through contaminated water. At his own expense he published a pamphlet entitled On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. Thirty-nine pages in length, the essay contained both a reasoned argument and documentary evidence to support his theory. As one example he cited the case of two rows of houses in a London neighborhood that faced each other. In one row many residents became cholera victims, while in the other row only one person was afflicted. It was discovered, Snow wrote, that "in the former bowl the slops of dirty water, poured down by the inhabitants into a channel in front of the houses, got into the well from which they obtained their water." Snow realized that such conditions existed in many neighborhoods and that if cholera epidemics were ever going to be eliminated, wells and water pipes would have to be kept isolated from drains, cesspools, and sewers. To avoid antagonizing the majority of physicians who rejected the theory that germs can cause disease, Snow did not directly state his view that a living organism caused cholera. Instead, he wrote of a "poison" that had the ability to "multiply itself by a kind of growth" within the membranes lining the digestive tracts of cholera victims, before being spread to new victims via polluted food or water. Snow's pamphlet had little effect on the thinking of his colleagues. It was just one of many tracts being published either as pamphlets or as articles in medical journals. A review in the London Medical Journal in September of 1849 complimented Snow for "endeavoring to solve the mystery of the communication of cholera," but the reviewer added that "other causes, irrespective of the water, may have been in operation" and that Dr. Snow could "furnish no proof whatever of the correctness of [his l views." Snow decided to publicize his views by giving lectures. At a talk to the Western Literary Institution on October 4 and in another talk to the Westminster Medical Society on October 13, he gave more examples with detailed descriptions of cases in several locations; but his views were met with skepticism. Each of Snow's colleagues had his own set of experiences to draw on. Dr. James Bird, for example, agreed that cholera might be communicated from person to person "under favorable conditions," but he disagreed that drinking water had "more than partial effect on spreading cholera." Dr. Lancaster pointed out that Snow's theory required the existence of "some sort of poison," whereas "no such poison has yet been demonstrated to exist." From the last month of 1849 until late in 1853, Britain experienced few cases of cholera. Snow continued to work on his theory that drinking water was the primary means of contagion. He accumulated data that had been collected in the epidemic of 1848-49 and that showed that patterns of the disease could be linked with specific water supplies. He also continued his pioneering studies of the effects of precisely measured doses of anesthetics. Other physicians remained highly skeptical of Snow's germ theory of cholera, but everyone praised his work on anesthetics that won him a reputation as the world's leading expert on their use. On April 7, 1853, he administered chloroform to Queen Victoria at the birth of her eighth child, Prince Leopold The following summer, cholera broke out in London in the district where Snow was working. He suspected that it was being spread by contaminated water piped in from the Thames River. He searched through municipal records and discovered that two private companies were supplying water to the district. One firm, the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company, was drawing water from an area along the Thames that was known to be polluted by sewage, whereas the other company, the Lambeth Water Company, had recently moved its intake facilities to a location above the sewer outlets. Snow decided to compare the mortality rates of consumers of the two sources of water. When he learned that both companies had water pipes beneath the paving stones in most streets, he saw a chance to conduct an experiment "on the grandest scale." Expressing his excitement, Snow wrote: No fewer than three hundred thousand people of both sexes, of every age and occupation, and of every rank and station, from gentle folks down to the very poor, were divided into two groups without their choice, and, in most cases, without their knowledge; one group being supplied with water containing the sewage of London, and amongst it, whatever might have come from the cholera patients-the other group having water quite free from such impurity. Snow began by looking at two subdistricts of south London, Lambeth and Kennington, where there had been forty-four cholera deaths prior to August 12. Determining which customers were served by which water company proved difficult. Most tenants did not know, and their landlords often lived elsewhere. Snow called at each house, traced landlords to their homes, and determined that thirty-eight of the forty-four deaths had occurred in houses supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company -- the company whose water came from a polluted source. Snow decided to expand his survey, but he needed help to canvas all the homes where cholera deaths had occurred. He engaged Dr. Joseph J. Whiting to visit half of the homes, while he visited the other half. When the two men tallied their figures, they learned that in the four-week period between July 8 and August 5, 286 of the 334 victims had used Southwark and Vauxhall water whereas just 14 of the victims had used Lambeth water. Snow took large statistical samples from other districts and discovered that deaths related to the two companies stood at a ratio of 71:5. Excited by his results, Snow believed that he had obtained "very strong evidence of the powerful influence which the drinking water containing the sewage of a town exerts on the spread of cholera when that disease is present." His critics were not impressed by the results of the survey. They continued to believe that cholera was caused by miasmas, not by germs or a waterborne poison, and they asserted that the enormous quantity of water in the Thames would sufficiently dilute any poison to render it harmless. Snow tried to agree with his opponents as much as possible. He downplayed his belief that germs caused cholera, asking his colleagues only to believe that the disease was spread by a type of poison that could somehow remain potent after dilution. He wrote, "The poison consists probably of organized particles, extremely small no doubt, but not incapable of indefinite division, so long as they keep their properties." Snow's critics pointed out that he had no evidence of the actual presence of the cholera "poison" in the water. Dr. Edmund A. Parkes wrote, "This array of evidence [does not prove] contamination of the water." In fact, Snow had accumulated statistical evidence that, by today's standards, would be considered worth acting upon, but because he was the first person to make use of a survey of the incidence and distribution of an epidemic in an effort to determine its cause, his evidence was seen as novel and unsound. In late August of 1853, cholera broke out suddenly and devastatingly in a neighborhood just a five-minute walk from Snow's home in the west London district of Soho. Snow immediately turned his attention to the outbreak. He first learned about it on Sunday, September 3, but it appeared to have begun the Thursday or Friday before. By the time Snow visited the affected neighborhood, many of the sick had already died. A yellow flag had been hung at the top of Berwick Street to alert the populace to the presence of cholera. People were fleeing the neighborhood as the dead were being hauled away in carts. On Sunday evening, Snow took a sample of the water from the public water pump on Broad Street because most of the fatalities had occurred in its vicinity. He knew that the companies that supplied water to that pump had a clean source of water, but he suspected that the well under the pump might have become contaminated by nearby sewer pipes. The sample of water that Snow drew from the pump looked fairly clear to him. He had been expecting to see cloudiness, which would indicate organic impurities. For comparison, he took samples of water from four nearby pumps in Warwick Street, Bridle Lane, Vigo Street, and Marlborough Street. There were no visible differences between the four samples. The next day Snow drew another sample from the Broad Street pump and took it to a microscopist, Dr. Arthur Hill Hassall, who reported that he saw a lot of organic matter in the water, but that this was not unusual. Because the physical evidence of pollution was not conclusive, Snow decided to gather statistical evidence-to compile a map showing where the victims lived and where they got their water. The following day Snow went to the General Register Office, where he copied records of the eighty-three cholera deaths that had occurred in the neighborhood for the week ending September 2. He obtained the name and address of each victim. He then returned to Broad Street, walked through the neighborhood, and calculated the distance from each victim's house to the nearest pump. He discovered that seventythree of the eighty-three deaths had occurred in homes closer to the Broad Street pump than to any other pump. After visiting the homes of the ten victims who had lived nearer to another pump, he was told that eight of those ten victims had drunk from the Broad Street pump-some preferred that water and others, who were children, had drunk from the pump on their way to school. Of the seventy-three victims who lived close to the pump, Snow learned that sixty-one of them had drunk the water. He calculated that the number of cholera deaths that could be expected in that neighborhood, as part of the general outbreak in London, was just fourteen. Therefore, he concluded that the higher than expected number of victims must be associated with the water from the Broad Street pump. Map showing areas within walking distance of the Broad Street pump. Snow gathered statistical evidence that showed a high incidence of cholera in homes and businesses within a short walk of the pump. Black bars indicate cholera deaths. On Thursday, September 6, Snow attended the meeting of the Board of Guardians. He showed them his evidence and recommended that they remove the Broad Street pump handle, so that no more people could become infected. The Board members were not persuaded by his argument but agreed to have the handle removed as one of several precautionary measures. They were chiefly concerned about miasmas, which they tried to eliminate by ordering the extensive spreading of lime in the streets. After the removal of the pump handle and the spreading of lime, the local cholera outbreak quickly ended. To determine what had caused the outbreak, the Board of Health appointed inspectors to look at atmospheric conditions in the neighborhood and sanitary conditions in the homes of victims. One prevalent theory, articulated in a letter to the Times of London, was that cholera was caused when a new sewer was constructed: "It must have disturbed the soil, saturated with the remains of persons deposited here during the great plague [of 1665].... A deadly miasmatic atmosphere has been for some months arising . . . poisoning the surrounding atmosphere." Inspectors examined the homes of victims on the assumption that they would find unsanitary conditions. The following Tuesday, September 11, they reported that, to their surprise, many of the victims had had clean homes. Meanwhile, Snow was conducting his own investigation. He visited a small coffee shop near the Broad Street pump where the proprietor mentioned that she normally served water from the pump with dinner and that nine of her customers had died. Snow began looking at other ways that people in the neighborhood might have drunk the water without drawing it directly from the pump. He found that local pubs mixed the water with spirits they served, and several shops put an effervescing powder into the water and sold it as "sherbet." Snow learned that eighteen of two hundred workers at a percussion cap factory had died; the factory supplied drinking water that came from the pump. At a dental supply house all seven workmen had died after drinking - pump water. Snow also tracked down people who had fled the neighborhood in the first few days of the epidemic, and he collected names and addresses of victims who had been taken to hospitals outside the neighborhood. Once he tallied the numbers, he realized that instead of the 83 deaths first reported, there were 197 deaths, all having occurred among people who had lived within a three-minute walk from the pump. Snow was able to gather hard evidence about cases that, at first, did not appear to be connected to the epidemic. He learned from Dr. David Fraser, a medical inspector for the General Board of Health, that the death of Susannah Eley, a widow in Hampstead, a few miles distant from Broad Street, was also linked to the Broad Street pump. The widow had insisted on having water from the pump brought to her every day. Her niece, who was visiting when the widow became ill, also drank the water and died a few days after her return to her home in Islington. Snow was curious about places in the neighborhood where there was a low incidence of cholera. He found that in a workhouse in the neighborhood, only 5 of 535 inmates had died-a low figure compared to nearby houses. The miasmists at the Board of Health had expected a higher than average rate at the workhouse since the inmates were poorly nourished, unclean, and of low morals -- indicators, by their standards, of susceptibility to disease. Snow learned, however, that the workhouse had its own source of water and therefore did not draw water from the Broad street pump. Miasmists also would have expected a high death rate at the Lion Brewery where workers drank beer -- the Board of Health advised that drinking alcohol was linked to cholera. In fact, none of the seventy-odd workers at the brewery had perished. Snow learned that they only drank beer and never touched the water from the pump. On September 25 inspectors from the Board of Health inspected the brick lining of the well under the Broad Street pump to be sure that no drainage from the sewer could enter it. After a cursory inspection inside the well, they found the lining apparently intact. A local surveyor, Jehoshaphat York, told them that the sewer was ten feet away and deeper than the bottom of the well. This seemed to disprove Snow's theory. Satisfied that the well had not been polluted and that the epidemic was over, the Board of Health reopened the Broad Street pump. People who had fled the neighborhood during the epidemic began returning to their homes by the last week in October. In November, Snow was asked by the Reverend Henry Whitehead to join a committee of the St. James Parish to investigate the causes of the outbreak. Snow was pleased by the prospect of working with Whitehead, who seemed to know everybody in the parish. Whitehead disagreed with Snow's theory about the cause of the epidemic, but he liked Snow's honest and straightforward method of investigation. Snow was at that time putting the final touches on the second edition of On the Mode of Communication of Cholera, and although he still had no physical evidence of pollution in the pump's water, he was convinced that the pump was the source of the epidemic. Hoping that a closer examination of the well beneath the pump would support his theory, Snow urged the parish committee to ask the Paving Board (responsible for water pumps) to reexamine the interior of the well. They did so and reported "that there was no hole or crevice in the brickwork of the well by which any impurity might enter." Snow had to admit in his publication that there was no direct evidence of any contamination of the Broad Street pump. After Snow's pamphlet was published, he gave copies to all the members of the parish committee. Whitehead read his copy and was impressed by Snow's array of facts, but he could not see how the pump could have been contaminated by the sewer line for just the few days when most of the deaths had occurred. Whitehead reasoned that if Snow's theory was correct, "the outbreak ought not so soon to have subsided, when much larger quantities of cholera excretions must have been continually pouring into the well through the ... sewers." Whitehead was not convinced about the pump, but he was as eager as Snow to solve the mystery. Broad Street, circa 1850, showing the pump in front of #40 In March of 1855, Whitehead was reviewing reports by the Registrar General about cholera deaths from the week ending September 3, 1854, when he came across an interesting item. He read, "At 40 Broad Street, 2nd September, a daughter, aged five months, [died of] exhaustion, after an attack of diarrhea four days previous to death." Whitehead remembered the case, but he had neglected to inquire at the time about the date of the attack. He now realized that if the child had first showed symptoms four days before September 2, then she had been the first cholera case in the neighborhood. He also realized that the Broad Street pump was located right in front of that house. Whitehead immediately went to see the infant's mother, Sarah Lewis. She described how when her baby was sick, she had cleaned the child's diapers in a pail, and then emptied the pail into the drain about a cesspool in front of her house. Whitehead was surprised to hear that there was a cesspool there. He had been under the false impression that all the cesspools on the street had been replaced by drainpipes that emptied directly into the recently installed sewer system. The cesspool that Mrs. Lewis had used was within a few feet of the Broad Street pump and the well beneath it. Whitehead informed the other members of the committee. Snow was especially interested in the news. On April 23 surveyor York supervised excavation of the cesspool, drains, and pump well. He found that, although it had not been obvious to previous inspectors, the brickwork of the pump well lining had decayed from the outside. The cesspool, which had been built to act as a trap that would overflow into the sewer drain, was so poorly constructed that it actually blocked the drain, forcing sewage to back up. The brickwork lining was loose, and the distance between the leaking cesspool and the pump well was just 2 feet 8 inches. The soil between the cesspool and the well showed signs of a steady percolation of waste from the cesspool into the well. Two previous inspections of the well had not uncovered this problem, because the soil outside the well had not been examined, and no one had known that there was a cesspool less than three feet away. The dates when the diaper water had been emptied into the cesspool corresponded to the early days of the outbreak, when most victims came down with cholera. After the child's death, no more diaper water had been emptied into the cesspool, and the epidemic had ended. As far as Whitehead and Snow were concerned, they had found the cause of the outbreak. The committee unanimously backed them in its report, but the General Board of Health dismissed Snow and Whitehead's conclusion. When John Snow died of a stroke on June 16, 1858, his theory about the spread of cholera had not gained any ground. The miasmists still prevailed. Snow died without knowing that the bacillus that causes cholera had been discovered in 1854 by the Italian anatomist Fillipo Pacini, who used a microscope to examine the intestinal walls of people killed by cholera. Pacini did not prove that the bacillus that he had discovered caused the disease, so his work remained obscure, and his reports were not translated into English. The germ theory of disease was not widely accepted until the 1860s, when the French chemist Louis Pasteur demonstrated by experiments that microscopic organisms can cause illness. Snow's final vindication came in 1884, when German microbiologist Robert Koch rediscovered, isolated, and cultured the cholera bacillus, Vibrio cholerae. For his persistent efforts to determine how cholera was spread and for the statistical and mapping methods he initiated, John Snow is widely considered to be the father of epidemiology. Sources Shephard, David A. E. John Snow: Anaesthetist to a Queen and Epidemiologist to a Nation. Cornwall, Prince Edward Island: York Point Publishing, 1995. Vinten-Johansen, Peter et al. Cholera, Chloroform, and the Science of Medicine: A life of John Snow. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003 John Snow. On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. 1855. CASES PROVING PERSON TO PERSON TRANSMISSION The first case of decided Asiatic cholera in London, in the autumn of 1848, was that of a seaman named John Harnold, who had newly arrived by the Elbe steamer from Hamburgh, where the disease was prevailing. He left the vessel, and went to live at No. 8, New Lane, Gainsford Street, Horsleydown. He was seized with cholera on the 22nd of September, and died in a few hours. Dr. Parkes, who made an inquiry into the early cases of cholera, on behalf of the then Board of Health, considered this as the first undoubted case of cholera. Now the next case of cholera, in London, occurred in the very room in which the above patient died. A man named Blenkinsopp came to lodge in the same room. He was attacked with cholera on the 30th September, and was attended by Mr. Russell of Thornton Street, Horsleydown, who had attended John Harnold. Mr. Russell informed me that, in the case of Blenkinsopp, there were rice water evacuations; and, amongst other decided symptoms of cholera, complete suppression of urine from Saturday till Tuesday morning; and after this the patient had consecutive fever. Mr. Russell had seen a great deal of cholera in 1832, and considered this a genuine case of the disease; and the history of it leaves no room for doubt. The following instances are quoted from an interesting work by Dr. Simpson of York (center left), entitled " Observations on Asiatic Cholera A: -----AThe first cases in the series occurred at Moor Monkton, a healthy agricultural village, situated to the northwest of York, and distant six miles from that place. At the time when the first case occurred, the malady was not known to be prevailing anywhere in the neighborhood, nor, indeed, at any place within a distance of thirty miles. "John Barnes, aged 39, an agricultural laborer, became severely indisposed on the 28th of December 1832; he had been suffering from diarrhea and cramps for two days previously. He was visited by Mr. George Hopps, a respectable surgeon at Redhouse, who, finding him sinking into collapse, requested an interview with his brother, Mr. J. Hopps, of York. This experienced practitioner at once recognized the case as one of Asiatic cholera; and, having bestowed considerable attention on the investigation of that disease, immediately enquired for some probable source of contagion, but in vain: no such source could be discovered. When he repeated his visit on the day following, the patient was dead; but Mrs. Barnes (the wife), Matthew Metcalfe, and Benjamin Muscroft, two persons who had visited Barnes on the preceding day, were all laboring under the disease, but recovered. John Foster, Ann Dunn, and widow Creyke, all of whom had communicated with the patients above named, were attacked by premonitory indisposition, which was however arrested. Whilst the surgeons were vainly endeavoring to discover whence the disease could possibly have arisen, the mystery was all at once, and most unexpectedly, unraveled by the arrival in the village of the son of the deceased John Barnes. This young man was apprentice to his uncle, a shoemaker, living at Leeds. He informed the surgeons that his uncle's wife (his father's sister) had died of cholera a fortnight before that time, and that, as she had no children, her wearing apparel had been sent to Monkton by a common carrier. The clothes had not been washed; Barnes had opened the box in the evening; on the next day he had fallen sick of the disease. "During the illness of Mrs. Barnes, her mother, who was living at Tockwith, a healthy village five miles distant from Moor Monkton, was requested to attend her. She went to Moukton accordingly, remained with her daughter for two days, washed her daughter's linen, and set out on her return home, apparently in good health. Whilst in the act of walking home she was seized with the malady, and fell down in collapse on the road. She was conveyed home to her cottage, and placed by the side of her bedridden husband. He, and also the daughter who resided with them, took the malady. All the three died within two days. Only one other case occurred in the village of Tockwith, and it was not a fatal case." "A man came from Hull (where cholera was prevailing), by trade a painter; his name and age are unknown. He lodged at the house of Samuel Wride, at Pocklington (lower center); was attacked on his arrival on the 8th of September, and died on the 9th. Samuel Wride himself was attacked on the 1lth of September, and died shortly afterwards. These comprise the first cases. "The next was that of a person named Kneeshaw, who had been at Wride's house. But as this forms one of a series connected with the former, furnished by Dr. Laycock, who has very obligingly taken the trouble to verify the dates and facts of the latter part of the series, it will be best to give the notes of these cases in that gentleman's own words. " 'My dear Dr. Simpson: - Mrs. Kneeshaw was attacked with cholera on Monday, September 9th, and her son William on the 10th. He died on Saturday the 15th; she lived three weeks; they lived at Pocklington. On Sunday, September 16th, Mr. and Mrs. Flint, and Mr. and Mrs. Giles Kneeshaw, and two children, went to Pocklington to see Mrs. Kneeshaw. Mrs. Flint was her daughter. They all returned the same day, except Mr. M. G. Kneeshaw, who stayed at Pocklington, until Monday, September 24th, when he returned to York. At three o'clock on the same day, he was attacked with cholera, and died Tuesday, September 25th, at three o'clock in the morning. [There had been no cholera in York for some time.] On Thursday, September 27th, Mrs. Flint was attacked, but recovered. On Saturday, September 29th, her sister, Mrs. Stead, came from Pocklington to York, to attend upon her; was attacked on Monday, October the 1st, and died October the 6th. "'Mrs. Hardeastle, of No. 10, Lord Mayor's Walk, York, was attacked with cholera on October 3rd, and died the same day. Miss Agar, residing with her, died of cholera on October 7th. Miss Robinson, who had come fromHull (lower center, Kingston upon Hull) to take care of the house, after the death of Mrs. Hardeastle and Miss Agar, was attacked, and died on October 11th. Mr. C. Agar, of Stonegate, York, went to see Mrs. Hardcastle on October 3rd, was attacked next day, and died October 6th, early in the morning. On Monday, October 8th, Mrs. Agar, the mother of Mr. C. Agar, was attacked, and on the same day, one of the servants; both recovered. They had lived with Mr. Agar. All the above dates and facts I have verified. " 'I am, dear Dr. Simpson, yours very truly, " 'T. LAYCOCK. " 'Lendal, December 1st, 1849.' " Several other instances of the communication of cholera, quite as striking as the above, are related in Dr. Simpson's work. The following account of the propagation of cholera has been published, along with several other histories of the same kind, in a pamphlet by Dr. Bryson.[2] "Mr. Greene, of Fraserburgh, gives the following account of the introduction of cholera into two villages in Scotland. Two boats, one belonging to Cairnbulgh and the other to Inveralochy, met at Montrose, and their crews on several occasions strolled through the town in company, although aware that it was at that time infected with cholera. On their passage homeward, they were obliged to put into Gourdon, where one man belonging to the Cairnbulgh boat died on the 22nd of September, after an illness of fourteen hours, with all the symptoms of cholera. Several of the men of both boats were at the same time attacked with serous diarrhea, of which three of them had not recovered when they reached their respective homes; nor indeed until the first cases of the epidemic broke out in the villages. "In Inveralochy the first case appeared on the 28th of September, three or four days after the arrival of the boat; the sufferer, the father of one of the crew, had been engaged in removing the cargo along with other members of his family. Two other cases occurred in this family; one on the 30th of September, and one on the 1st of October. "In Cairnbulgh, the first cases appeared on the 29th and 30th of September respectively, and both patients had also been engaged in removing the cargo of the boat (shellfish) belonging to that village. No other cases appeared until the 3rd of October; so that from the 28th of September to the 3rd of October none were attacked in either village, but those who had come in contact with the suspected boats, or their crews. "The subsequent cases were chiefly among relatives of those first attacked; and the order of their propagation was as follows. In Inveralochy, the first case was the father of a family; the second, his wife; the third, a daughter living with her parents; the fourth, a daughter who was married and lived in a different house, but who attended her father and mother during their illness; the fifth, the husband of the latter; and the sixth, his mother. Other cases occurred at the same time, although they were not known to have communicated with the former. One of them was the father of a family; the second his son, who was seized the day after his father, and a daughter the next day." The following instances of communication of cholera are taken from amongst many others in the "Report on Epidemic Cholera to the Royal College of Physicians", by Dr. Baly. "Stockport (upper left). (Dr. Rayner and Mr. J. Rayner, reporters). Sarah Dixon went to Liverpool (upper center), September 1st, to bury her sister, who had died of cholera there; returned to Stockport on September 3rd; was attacked with cholera on the 4th; was taken home by her mother to her mother's house, a quarter of a mile distant; was in collapse, but recovered. Her mother was attacked on the 1lth, and died. The brother, James Dixon, came from High Water to see his mother, and was attacked on the 14th. "Liverpool. (Mr. Henry Taylor, reporter.) A nurse attended a patient in Great Howard Street (at the lower part of the town), and on her return home, near Everton (the higher part of the town), was seized, and died. The nurse who attended her was also seized, and died. No other case had occurred previously in that neighborhood, and none followed for about a fortnight. "Hedon (lower right). (Dr. Sandwith, reporter.) Mrs. N. went from Paul, a village close to the Humber, toHedon, two miles off, to nurse her brother in cholera; the next day, after his death, went to nurse Mrs. B., also at Hedon ; within two days was attacked herself; was removed to a lodging-house ; the son of the lodging-house keeper was attacked the next day, and died. Mrs. N.'s son removed her back to Paul; was himself attacked two days afterwards, and died." It would be easy, by going through the medical journals and works which have been published on cholera, to quote as many cases similar to the above as would fill a large volume. But the above instances are quite sufficient to show that cholera can be communicated from the sick to the healthy; for it is quite impossible that even a tenth part of these cases of consecutive illness could have followed each other by mere coincidence, without being connected as cause and effect. NOT COMMUNICATED BY MEANS OF EFFLUVIA Besides the facts above mentioned, which prove that cholera is communicated from person to person, there are others which show, first, that being present in the same room with a patient, and attending on him, do not necessarily expose a person to the morbid poison; and, secondly, that it is not always requisite that a person should be very near a cholera patient in order to take the disease, as the morbid matter producing it may be transmitted to a distance. It used to be generally assumed, that if cholera were a catching or communicable disease, it must spread by effluvia given off from the patient into the surrounding air, and inhaled by others into the lungs. This assumption led to very conflicting opinions respecting the disease. A little reflection shows, however, that we have no right thus to limit the way in which a disease may be propagated, for the communicable diseases of which we have a correct knowledge spread