Moltmann, Way of Jesus Christ, p. 151

advertisement

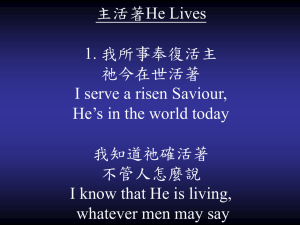

Sitaatteja Sovitusoppi nykyteologiassa Syksy 11 #1 Admittedly, in the past the Christian doctrine of salvation was often applied solely to the eternal situation of human beings in God’s sight, in order that eternal salvation might be related to the fundamental existential situation of men and women: their separation from God, their transience, finitude and mortality. This meant that often enough this doctrine ignored the actual, practical human situation, in its real misery. Moltmann, Way of Jesus Christ, p. 45. #2 “The Spirit, therefore, descending under the predestined dispensation, and the Son of God, the Only-begotten, who is also the Word of the Father, coming in the fulness of time, having become incarnate in man for the sake of man, and fulfilling all the conditions of human nature.” Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.17.4 #3 “Luther’s teaching can only be rightly understood as a revival of the old classic theme of the Atonement as taught by the Fathers, but with a greater depth of treatment.” Aulen, Christus Victor, p. 102. This combining of the two traditions is well illustrated in the two rubrics under which Althaus looks at the topic of atonement in the Reformer: “Christ’s Work as Satisfaction to God” and “Christ’s Work as a Battle with the Demonic Powers.” Althaus, Theology of Martin Luther, pp. 201-17 #4 Atonement theology starts with violence, namely the killing of Jesus. The commonplace assumption is that something good happened, namely the salvation of sinners, when or because Jesus was killed. It follows that the doctrine of atonement then explains how and why Christians believe that the death of Jesus—the killing of Jesus—resulted in the salvation of sinful humankind. Weaver, Nonviolent Atonement, p.2. #5 “The trial and punishment of Jesus itself condemns, in some measure, all other trials and punishment, and all forms of alien discipline. . . . The only finally tolerable, and non-sinful punishment, for Christians, must be the self-punishment inherent in sin.” J. Milbank, Theology and Social Theory: p. 421 # 6a “The drama of salvation starts and ends with violence, and without violence its central act is unthinkable.” Volf, Exclusion and Embrace, pp. 29091. #6b “The end of the world is not violence, but a nonviolent embrace without end..The world to come is ruled by the one who on the cross took violence upon himself in order to conquer the enmity and embrace the enemy. The Lamb’s rule is legitimized not by the ‘sword’ but by its ‘wounds’. #7 “Metaphors have to be weighed as to their importance and relevance. Their frequency and usage in the biblical canon, alignment with Christian tradition, and theological coherence serve as appropriate criteria. To put it other way, there needs to be some kind of ‘systematic’ relating of metaphors with others” VMK, Christ and Reconciliation #8 “[W]hether Christ rectifies erroneous views concerning an unchangeable fact, namely the love of God… or whether Christ is the author of a changed situation.” [In the latter case,] “the death of Christ must be seen as a real overcoming of the misery that consists of our having fallen into sin and death and the related estrangement from God… [This means that] in interpreting the death of Jesus, we must make the nature of the event normative for the evaluation, selection, and use of the interpretive models available.” Pannenberg, ST 2:410, #9 Baptized by John the Baptist, filled with the Holy Spirit: to preach the kingdom of God to the poor, to heal the sick, to receive those who have been cast out, to revive Israel for the salvation of the nations, and to have mercy upon all people. Moltmann, The Way of Jesus Christ, p. 150. # 10 [Jesus] fought dehumanization by placing human need above even the most sacred traditions such as Sabbath purity (Mark 2:23–3:6). Therefore the oppressed were conscientized in his presence. Blind Bartimaeus, whom the crowds silenced, was given voice and healed by Jesus (Mark 10:46-52). An unnamed woman with a flow of blood and no financial resources touched Jesus and subsequently “told him the whole truth” (Mark 5:25-34). Jesus fought sin by denouncing everything—whether religious, political, economic, or social—that alienated people from God and from their neighbor. Pope-Levison and Levison, Jesus in Global Contexts, p. 35. # 11a Heb. 5:8-9 “should not be seen as contrasting filial closeness to the Father” but rather as an expression of the “tension between learning obedience in time and pretemporal sonship.” Jesus’s obedience to the Father then “is not alien obedience of the slave . . . [but rather] an expression of his free agreement with the Father.” Pannenberg, ST 2:316. 11b “In patristic tradition, freedom and obedience are seen as inseparable. The Trinity itself is a perfect communion of love, and not only of love but, we can dare to say, also of obedience. . . . Obedience is part of the mystery of love and humility. Those who live in mutual obedience and love, as do the persons of the Trinity, share a single nature and therefore a single will in perfect harmony.” Simeon Rodger, “The Soteriology of Anselm of Canterbury, an Orthodox Perspective,” #11c “To suffer and to be rejected are not identical. Suffering can be celebrated and admired. It can arouse compassion. But to be rejected takes away the dignity from suffering and makes it dishonourable suffering. To suffer and be rejected signify the cross.” Moltmann, Crucified God, p. 55 # 12 At the centre of Christian faith is the history of Christ. At the centre of the history of Christ is his passion and his death on the cross. We have to take the word ‘passion’ seriously in both its senses here, if we are to understand the mystery of Christ. For the history of Christ is the history of a great passion, a passionate surrender to God and his kingdom. And at the same time and for that very reason it became the history of an unprecedented suffering, a deadly agony. At the centre of Christian faith is the passion of the passionate Christ. The history of his life and the history of his suffering belong together. They show the active and the passive side of his passion. Moltmann, Way of Jesus Christ, p. 151 # 13 Basically, every Christian theology is consciously or unconsciously answering the question, ‘Why hast thou forsaken me’, when their doctrines of salvation say ‘for this reason’ or ‘for that reason’. In the face of Jesus’ death-cry to God, theology either becomes impossible or becomes possible only as specifically Christian theology. Christian theology cannot come to terms with the cry of its own age and at the same time always be on the side of the rulers of this world. But it must come to terms with the cry of the wretched for God and for freedom out off the depths of the sufferings of this age… # 13 cont. …Sharing in the sufferings of this time, Christian theology is truly contemporary theology. Whether or not it can be so depends less upon the openness of theologians and their theories to the world and more upon whether they have honestly and without reserve come to terms with the death-cry of Jesus for God. Moltmann, Crucified God, p. 153. # 14 “What happened on the cross was an event between God and God. It was a deep division in God himself, in so far as God abandoned God and contradicted himself, and at the same time a unity in God, in so far as God was at one with God and corresponded to himself.” Moltmann, Crucified God, p. 244. “God’s being is in suffering and suffering in God’s being itself,” because God is love. Ibid., p. 227. # 15 “As mothers’ hearts rend with their children’s suffering more readily than with their own, so God’s unsurpassed love for humans is narrated scripturally as a love both that is and that gives up the beloved one who dies in compassion for us.” Lisa Sowle Cahill, “The Atonement Paradigm: Does It Still Have Explanatory Value?” 429-30 #16 “The passion of Jesus Christ is not an event which concerned only the human nature that the divine Logos assumed, as though it did not affect in any way the eternal placidity of the trinitarian life of God. In the death of Jesus the deity of his God and Father was at issue.” Pannenberg, ST 2:314. # 17 “God does not love us because Christ died for us, but that Christ died for us because God loves us, and his sacrifice is an expression of this love. The cross of Christ was not given by man to change God, but given by God to change man.” Culpepper, Interpreting the Atonement, p. 131… # 17 cont. … “Far from effecting any change in the attitude of God toward man in the sense of turning hostility into love or making a friend of an enemy, the cross of Christ gave expression to the love of God for man which was in God’s heart from all eternity, working out in history God’s eternal purposes in Christ.” ibid. # 18a “Sin becomes an excuse for persecution, righteousness becomes defined as submission to scapegoating, and judgment uses violence against violence. The historical task of the Holy Spirit . . . is to prove this wrong, by testimony to Christ” Heim, Saved from Sacrifice, pp. 154. # 18b [In terms of its salvific effects, the glorifying work of the Spirit serves the consummation of redemption and atonement since it brings about the] “overcoming of mortality and consummation by participation in the eternal life that by the Spirit unites the Son to the Father and that has already come as the future of creation in his resurrection from the dead.” Pannenberg, ST, 2:396. # 19a “The Lord has risen” (Luke 24:34). What in Greek is a single word joyfully proclaims the climax of the drama of redemption. “The Lord has risen” contains in nuce the resolution of the dramatic tension built up over centuries: How would God make good on his promise? How could God keep covenant with covenant breakers? How would God bless all the nations through the seed of Abraham? “The Lord has risen.” There is a density in this statement that calls for thought and “thick description.” While the explicit subject of this sentence is Jesus Christ, the implied subject is God the Father who raised him. And while the explicit predicate is resurrection, the implicit predicate is Jesus’ crucifixion. Vanhoozer, Drama of Doctrine, p. 41. #19b The Spirit proceeds “from this event [of the cross] between the Father and the Son” and thus is the “boundless love which proceeds from the grief of the Father and the dying of the Son” and reaches out to humanity. [As the bond of love, the Spirit represents divine unity in the midst of deepest separation.] “What proceeds from this event between Father and Son is the Spirit which justifies the godless, fills the forsaken with love and even brings the dead alive.” Moltmann, Crucified God, p. 244-5 #20 In the preaching and theology of the early church, the linking of the cross with the resurrection (and ascension) becomes a key theme: Acts 2:23-24; 3:14-15; 4:10; 5:30; 10:39-40; Romans 6:3-11; 8:34; 1 Peter 1:19-21; 3:18, 2122 # 21 [On the basis of the hypostatic union principle, Christian theology affirms that] “in the risen Christ . . . there is involved an hypostatic union between eternity and time, eternity and redeemed and sanctified time, and therefore between eternity and new time.” Torrance, Space, Time and Resurrection, p. 98. # 22 If we wished to confine ourselves to the endorsement, ‘resurrection’ would be no more than an interpretative theological category for his death; and all that would remain would be a theology of the cross. If we were to concentrate solely on the fulfillment, the Easter Christ would replace and push out the crucified Jesus. But if, . . . the earthly Jesus is ‘the messiah on the way’, and the Son of God in the process of his learning, then Easter endorses and fulfils this life history of Jesus which is open for the future. At the same time, however, resurrection, understood as an eschatological event in Jesus, is the beginning of the new creation of all things. Moltmann, Way of Jesus Christ, p. 171. #23 “Jesus, as the human face of God, was not simply a temporary and fleeting vision on this earth. He was the divine attempt to bridge the primordial alienation between God and humanity. All people everywhere, regardless of their respective location in space and time, had through him the opportunity to be confronted with the gospel, God’s word of salvation.” Schwarz, Christology, p. 294. # 23 He showed Himself quite unequivocally to be the creature, the man, who in provisional distinction from all other men lives on the God-ward side of the universe, sharing His throne, existing and acting in the mode of God, and therefore to be remembered as such, to be known once for all as this exalted creature, this exalted man, and henceforth to be accepted as the One who exists in this form to all eternity. The most important verse in the ascension story is the one which runs: “A cloud received him out of their sight” (Ac. 19). In biblical language, the cloud does not signify merely the hiddenness of God, but His hidden presence, and the coming revelation which penetrates this hiddenness. It does not signify merely the heaven which is closed for us, but the heaven which from within, on God’s side, will not always be closed. Barth, CD III/2, p. 454